Robert Gottlieb, who famously edited the works of Joseph Heller, John Le Carré, John Cheever, and Toni Morrison (who was herself a literary editor before beginning her career as a novelist at age 39), said of editing books that the often-mysterious task "is simply the application of the common sense of any good reader." In the same Paris Review interview, he cautions against the "glorification of editors,” and says that "the editor's relationship to a book should be an invisible one."

While an editor’s work is frequently just that—invisible—to the public, there have been a number of book editors over the years who have been credited with radically improving or reshaping the works of renowned authors. While the value of an extremely proactive approach to literary editing can be debated, it’s hard to imagine that anyone who has edited a number of great novels deserves no credit for their success, even if, like Gottlieb, they insist otherwise.

While an editor’s work is frequently just that—invisible—to the public, there have been a number of book editors over the years who have been credited with radically improving or reshaping the works of renowned authors. While the value of an extremely proactive approach to literary editing can be debated, it’s hard to imagine that anyone who has edited a number of great novels deserves no credit for their success, even if, like Gottlieb, they insist otherwise.

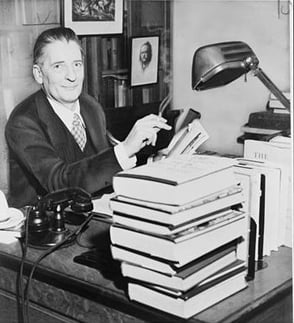

Perhaps the most famous American editor of the last century (aside from Jackie Kennedy, who actually became an editor after leaving the White House) was Maxwell Perkins. Perkins’ career began in earnest after he signed F. Scott Fitzgerald to a contract at Scribner and edited his acclaimed first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920). He would continue working with Fitzgerald throughout his career (making famously substantial edits to The Great Gatsby (1925) that many consider to have been crucial to its enduring success) and through him met Ernest Hemingway, whose works he also famously edited and championed in the face of those who objected to Hemingway’s use of profanity.

As if his work with those two famous Lost Generation writers did not sufficiently solidify his impact on 20th century letters, he also famously convinced Thomas Wolfe to cut 90,000 words from the final draft of Look Homeward, Angel (1929), in addition to working with Erskine Caldwell, Alan Paton, and James Jones.

Of course, not everyone is willing to give editors the benefit of the doubt. Famed Russian-born novelist Vladimir Nabokov famously called editors ‘pompous avuncular brutes’, no doubt because many editors would have urged him to add a coma before ‘avuncular’. And it is certainly true that there is always a risk of cutting the wrong thing or of fixating on the wrong details.

Of course, not everyone is willing to give editors the benefit of the doubt. Famed Russian-born novelist Vladimir Nabokov famously called editors ‘pompous avuncular brutes’, no doubt because many editors would have urged him to add a coma before ‘avuncular’. And it is certainly true that there is always a risk of cutting the wrong thing or of fixating on the wrong details.

In Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857), Emma Bovary’s eyes change color without warning throughout the book. Virginia Woolf freely admits "all my facts about lighthouses are wrong." A wrongheaded editor might have been tempted to resolve these ‘issues’, just as Thomas Wentworth Higginson famously removed most of Emily Dickinson’s radical punctuation while acting as her literary executor.

An only slightly less extreme example of the Higginson phenomenon comes via the story of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations (1861). Dickens and his contemporary Edward Bulwer-Lytton (who was wildly successfully in his timing, coining the phrase ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’ as well as being the first to use the now-clichéd opening ‘it was a dark and stormy night) famously traded edits on one another’s novels.

Though it is hard to measure the impact that Dickens had on Lytton’s work, Lytton’s editing of Dickens gives us at least one famous example of misguided editorial advice. Lytton insisted that the original ending of Great Expectations was too grim, and convinced Dickens to write a new one in which the possibility of Pip and Estella marrying is left open as a possibility, sparking an aesthetic debate over the relative merits of each ending that has lasted through the centuries.

Of course there are instances were aggressive and extreme editors thoroughly changed authors’ works for the better. Gordon Lish, for instance, is known to have made massive and insistent cuts to the stories that comprised Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981). Lish is supposed to have sometimes cut more than half of what was in Carver’s original versions, adding his own details and embellishments as he saw fit. The result was one of the classics of American short fiction. Lish’s tactics helped to define the minimalist style for which Carver would become known. Carver seems to have had mixed feelings pertaining to Lish’s impact, sometimes offering up displays of gratitude and sometimes seeming to suggest that Lish in some way bastardized the stories. Carver notably described Lish’s edits as "surgical amputation and transplant that might make them someway fit into the carton so the lid will close," and late in life arranged to publish the original, unaltered versions of some of his stories.

On the topic of an editors’ ideal impact, it may be useful to look at the relationship between David Foster Wallace and his editor Michael Pietsch. Pietsch worked closely with the late novelist on his magnum opus, Infinite Jest, staying in close contact with him and offering up considerable advice and feedback throughout the editing process. Though it is difficult to gauge the impact of Pietsch’s edits, the result was an undeniable success.

On the topic of an editors’ ideal impact, it may be useful to look at the relationship between David Foster Wallace and his editor Michael Pietsch. Pietsch worked closely with the late novelist on his magnum opus, Infinite Jest, staying in close contact with him and offering up considerable advice and feedback throughout the editing process. Though it is difficult to gauge the impact of Pietsch’s edits, the result was an undeniable success.

Following David Foster Wallace’s tragic suicide in 2008, Pietsch’s relationship with Wallace put him in the position of a sort of literary executor, tasked with salvaging one last novel from the confusion of Wallace’s notes and early drafts. The result was The Pale King (2011), which would go on to earn a place as one of that year’s Pulitzer Prize finalists (the highest honor bestowed by the Pulitzer committee that year, after they famously refused to designate an actual winner). The posthumous novel’s success no doubt speaks volumes (in this case probably heavily footnoted volumes) about the capacity good editors have to see an author’s vision realized in its best (and sometimes only) possible form.