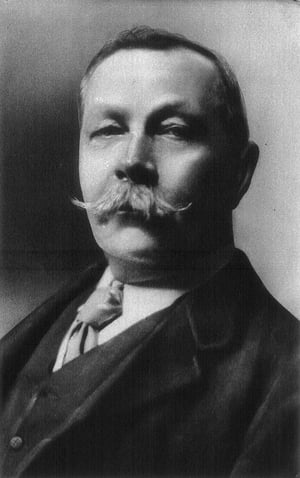

If you’re good with dates, dear reader, you no doubt have a number of objections ready based simply on the title of this blog post. The Hound of the Baskervilles, which represents Sherlock Holmes’ first appearance after he was unceremoniously killed off by his author, actually appears in 1901, with a slow trickle of additional Holmes stories and other writings throughout the aughts, teens, and twenties. So, in point of fact, Arthur Conan Doyle is the Arthur Conan Doyle of the 20th century. We could call Michael Crichton the Conan Doyle of the Cold War, but Jurassic Park (1990) was published after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Let’s say instead that Crichton, who was born 12 years after Doyle’s death, could be Arthur Conan Doyle reincarnated.

It’s still a bold claim once you’ve moved past the pedantry. But a handful of surface similarities in the biographies of these two classic pulp authors (both trained as medical doctors, both open-minded occultists) might, arguably, suggest something deeper—a kind of literary kinship, and a similar (though by no means identical) impact on a generational imagination. If we’re lucky, this kinship might reflect something back to us about 20th century readers and film-goers.

Doctors of Letters

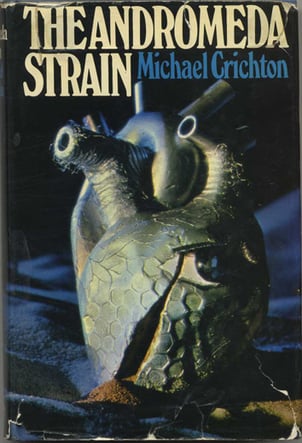

People sometimes forget that Michael Crichton was the mind behind the hit television show ER (1994-2009). And they much more frequently forget that he actually wrote a book of medical case studies that was published just after his breakout sci-fi opus, The Andromeda Strain (1969). Of course, Crichton had always intended to be a writer, and only found himself taking the med school path in the most convoluted way possible (he switched majors at Harvard because he theorized that a particular professor held a grudge against him and was artificially deflating his grades—to test this theory, he handed in one of George Orwell’s essays as his own, receiving a B-minus for his efforts). But it’s hard to deny that his medical training and practice had a significant impact on his output as a writer. One of the hallmarks of his style is the scattered scientific content throughout his works.

Whether he’s discoursing on chaos theory in Jurassic Park or cybernetics in his Westworld (1973) screenplay, “Readers come away entertained and also with the belief, not entirely illusory, that they have actually learned something,” (says the New York Times, anyway). Conan Doyle, of course, famously wrote his earliest short stories while in medical school, and would practice medicine successfully throughout his early life. Though the impact on his works was sometimes subtler than in Crichton’s, it’s hard to deny the importance of the scientific method itself to Conan Doyle's Holmes canon. The famous detective’s methods are logically and scientifically rooted in a way that was not only a first in the fictional world—it was also years ahead of the methods used in actual police work. Though it might not always have been accurate to say that Conan Doyle’s readers came away feeling as though they had learned something, certainly a methodology for solving problems had been elucidated.

Flirting with the Occult

Though Conan Doyle extolled the virtues of hyper-rationality in his work, in his personal life the primacy of logic sometimes went out the window. Case in point: his obsession with the occult. In 1893 he joined the Society for Psychical Research, whose mission was ostensibly to investigate the possibility of the paranormal. Over time, however, the group dedicated most of its time to exposing fraudulent magicians and psychics, which led to Conan Doyle’s resignation on the basis the group had become too skeptical of the possibility of authentic occult phenomena. In the 1920s, Conan Doyle struck up a friendship with Harry Houdini, which ended contentiously when the latter insisted that he was not, personally, possessed of supernatural abilities.

There’s nothing in Crichton’s biography to suggest that his interest in the super-liminal edges of scientific understanding ever went this far, but he certainly did visit psychics in the ‘70s and ‘80s. As a practice, it’s hardly out of the ordinary, but it puts what some readers see as the techno-skepticism of Jurassic Park and Prey (2002) into stark relief. If there is a similarity in the works of these two authors, could these shared biographical details account for them? On the surface, both were masters of a particular kind of adventure story—but beneath that surface, might there be a similar kind of nostalgia, even paranoia, at play? At the risk of overburdening one fact with significance, it seems telling that both writers published a novel titled The Lost World (1912 and 1995, respectively)—as though the pair with both searching for something that existed just beyond their perception.

The Death of the Protagonist

There’s no sense in overstating the point. Yes, Conan Doyle and Crichton are doctors turned bestselling genre writers with some level of personal interest in the supernatural, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t stark differences between the two. For one thing, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s literary output gave us two of the great literary characters of all time in Holmes and Watson, while creating lifelike characters never seems to have numbered among Crichton’s literary concerns.

Of course, this difference in particular might be telling. Though the pair approach their literary work with similar backgrounds and similar scientifically-motivated methodologies, this crucial difference might reflect something meaningful about the writers’ two distinct eras. Where the 19th century reader, perhaps with Daniel Defoe and Jane Austen under her belt, was engaged in helping to define the modern conception of the individual, a globalizing Cold War and post-Cold War culture could be said to have pushed back on the individual's importance. We see this shift in understanding pretty clearly in the more self-consciously literary novels of Thomas Pynchon, Robert Coover, and their ilk, but it’s telling that Crichton’s novels reflect it in the world of sci-fi and techno-thrillers. It suggests, maybe, that if Arthur Conan Doyle were alive today the Holmes project might seem passé, or at least less interesting than the perils of machine learning or self-driving cars.