As a community of readers and writers, we are all too familiar with the sentiments of Bilbo Baggins. “Look, I know you doubt me, I know you always have. And you're right. I often think of Bag End. I miss my books. And my armchair. And my garden. See, that's where I belong. That's home…” We are a people torn between reading about adventures, and creating one of our own—rising from the safety of our armchairs to take on the persona of the heroes and heroines we’ve grown to know and love. Of course, leaving our comfort zones always comes with a risk: the risk that our pursuits will not go as planned, and that we will face doubt, rejection, and failure.

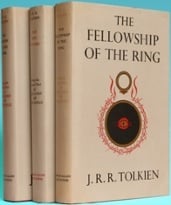

Such experiences were not foreign to J.R.R. Tolkien, as his initial book in the Lord of the Rings series, The Fellowship of the Ring was not received by everyone with open arms at the time of it’s publication. Edmund Wilson, seemingly the Simon Cowell of the literary critics, was particularly harsh in his assessment of Tolkien’s work, calling it “juvenile trash.” But as the old saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

Such experiences were not foreign to J.R.R. Tolkien, as his initial book in the Lord of the Rings series, The Fellowship of the Ring was not received by everyone with open arms at the time of it’s publication. Edmund Wilson, seemingly the Simon Cowell of the literary critics, was particularly harsh in his assessment of Tolkien’s work, calling it “juvenile trash.” But as the old saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

The Fellowship of the Ring was published in 1954, and served as the first book in a trilogy following the introduction of The Hobbit in 1937. Throughout its pages, Tolkien created another world so rich in detail and history, that any reader might start to wonder if they could pack a U-Haul truck and move there. From Hobbit holes to fiery mountains, The Fellowship of the Ring follows the journey of a misfit group on a noble mission to conquer evil. Though perhaps a bit darker than its predecessor, it is a book that dances on the literary line between childhood and adulthood. The fantastical nature lends itself to the fairytale genre, but the complex nature of the plot can enthrall people of all ages.

Like many series today, Lord of the Rings was not just a compilation of books, but a passage to a different life. It captured the attention of young readers with characters likes hobbits, wizards, and dragons, but gained the allegiance of parents with messages of hope, persistence, and honor. W.H. Auden frequently argued that Tolkien’s writing could be enjoyed by everyone, because Middle Earth was a world “of intelligible law, not mere wish.”

Like many series today, Lord of the Rings was not just a compilation of books, but a passage to a different life. It captured the attention of young readers with characters likes hobbits, wizards, and dragons, but gained the allegiance of parents with messages of hope, persistence, and honor. W.H. Auden frequently argued that Tolkien’s writing could be enjoyed by everyone, because Middle Earth was a world “of intelligible law, not mere wish.”

The more time passed, and the more Tolkien wrote, the farther the Lord Of The Rings triology drifted from Wilson’s original review. Though he may not have appreciated Tolkien’s writing at the time, I imagine Edmund Wilson would have eventually had a change of heart. After reading all three books, we’d see him standing in line at the local cinema at 11:59PM, donning 3-D glasses and a Frodo t-shirt, eagerly waiting to see the new movie.