Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature at UC Irvine, and he is a world-renowned playwright, novelist, essayist, and short story writer. Similar to many authors from the African continent, Ngũgĩ began writing in English, or the language of colonization in Kenya and throughout many regions of the continent. Yet throughout his career, Ngũgĩ has rejected the notion that African novelists must write in the language of the colonizer and has begun writing in his native Gĩkũyũ, a language spoken in Kenya and in parts of Tanzania and Uganda. Ngũgĩ translates his own work into English, and has become what he describes as “a language warrior,” or someone who wants “to join all those others in the world who are fighting for marginalized languages.” If you haven’t read the works of Ngũgĩ, we’d like to take this opportunity to make an introduction.

Early Writing Life and Works

Ngũgĩ has written works in many genres, and in multiple languages. He was born in Kenya as James Ngugi, and he spent his early life in the country. He spent four years in Kampala, Uganda, at Makerere University, which he details in his autobiographical Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Memoir of a Writer’s Awakening (2016). From the early 1960s through the mid-1970s, Ngũgĩ wrote a number of texts in English. In 1962, while at Makerere University, he wrote his first play, The Black Hermit, which was produced that year and published a year later. He wrote his first two novels soon after, including Weep Not, Child (1964) and The River Between (1965). His third novel, A Grain of Wheat (1967), largely propelled him into international readership, a position solidified with his later novel Petals of Blood (1977).

Ngũgĩ has written works in many genres, and in multiple languages. He was born in Kenya as James Ngugi, and he spent his early life in the country. He spent four years in Kampala, Uganda, at Makerere University, which he details in his autobiographical Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Memoir of a Writer’s Awakening (2016). From the early 1960s through the mid-1970s, Ngũgĩ wrote a number of texts in English. In 1962, while at Makerere University, he wrote his first play, The Black Hermit, which was produced that year and published a year later. He wrote his first two novels soon after, including Weep Not, Child (1964) and The River Between (1965). His third novel, A Grain of Wheat (1967), largely propelled him into international readership, a position solidified with his later novel Petals of Blood (1977).

In 1977, Ngũgĩ was imprisoned for one year as a result of his anti-colonial literature. When asked about this period of imprisonment during a Los Angeles Review of Books interview, the writer detailed the oppressive space of the prison and his acts of resistance within: “by writing secretly.” As he explained, “I wrote a novel, Devil on a Cross, in Gĩkũyũ on toilet paper with a pen they had given me to write a confession.” This novel became emblematic of Ngũgĩ’s commitment to resisting colonial language imposition and writing in Gĩkũyũ.

Colonial Language and Decolonising the Mind

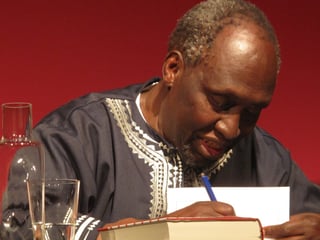

_PD.jpg?width=320&name=Ngu%CC%83gi%CC%83_wa_Thiong'o_(signing_autographs_in_London)_PD.jpg) In 1986, Ngũgĩ published Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. The text has become a significant work in postcolonial studies and literary theory, drawing out the harms of colonial language imposition and the harms upon the Anglophone writer. As he explains in that text:

In 1986, Ngũgĩ published Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. The text has become a significant work in postcolonial studies and literary theory, drawing out the harms of colonial language imposition and the harms upon the Anglophone writer. As he explains in that text:

“In Kenya, English became more than a language: it was Slanguage, and all the others had to bow before it in deference . . . . English became the measure of intelligence and ability in the arts, the sciences and all the other branches of learning. English became the main determinant of a child’s progress up the ladder of formal education.”

With the imposed social and educational requirement of English, Kenyan languages became subordinated along with Kenyan culture. As Ngũgĩ questions: “What was the colonial system doing to us Kenyan children? What were the consequences of, on the one hand, this systematic suppression of our languages and the literature they carried, and on the other the elevation of English and the literature it carried?” He addresses these key questions in Decolonising the Mind, while emphasizing the significance of indigenous and other minority languages throughout his essays and works of fiction.

As we mentioned, Ngũgĩ now translates his own works from Gĩkũyũ, the language in which he writes, into English. The author’s most recent memoir, Birth of a Dream Weaver, is a great place to start if you’re interested in learning more about Ngũgĩ. We’d be remiss, however, if we didn’t recommend that you also pick up copies of the writer’s other memoirs along with his critical essays, short stories, novels, and plays. Happy reading!

Image source.