Whose role is it to write postwar German fiction? Since World War II ended, numerous writers of great acclaim have come out of West Germany and the GDR, and later from reunified Germany. For instance, you might be familiar with the works of the West German novelists Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass, or with the GDR literature of Christa Wolf. While many writers of the immediate postwar period returned to the rise of Nazi Germany and its aftermath in their works, W.G. Sebald is a bit of an interesting case.

An article in The New Yorker* described Sebald as “one of contemporary literature’s most transformative figures.” And indeed, his novels, poetry, and nonfiction essays have provided readers across the globe with new lenses into how we remember the rise of the Third Reich and the perpetration of the Holocaust in relation to twentieth- and twenty-first-century Germany.

The History of W.G. Sebald

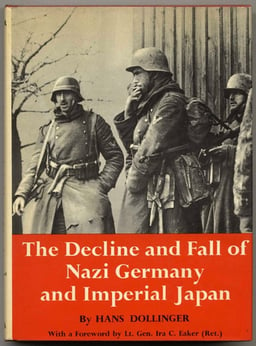

Sebald didn’t start out as a novelist—at least not as a widely translated, internationally acclaimed one. The writer, born Winifried Georg Maximilian Sebald in May of 1944, initially hailed from the Bavarian forest in Germany. His father joined the military in 1929 and remained in the army through Hitler’s rise in the 1930s. According to Sebald, his parents came from “conventional, Catholic, anti-communist, working-class backgrounds.” It was not a commitment to National Socialism that kept Sebald’s father involved in the party that would come to perpetrate the Holocaust and related crimes against humanity during World War II, but rather economics. As Sebald has explained, “they experienced upward mobility in the 1930s, like so many Germans; my father finished the war as a captain. Fascism did away with the class system—as in France under Napoleon, and in stark contrast to Britain, where it dominates the army to this day.”

Sebald didn’t start out as a novelist—at least not as a widely translated, internationally acclaimed one. The writer, born Winifried Georg Maximilian Sebald in May of 1944, initially hailed from the Bavarian forest in Germany. His father joined the military in 1929 and remained in the army through Hitler’s rise in the 1930s. According to Sebald, his parents came from “conventional, Catholic, anti-communist, working-class backgrounds.” It was not a commitment to National Socialism that kept Sebald’s father involved in the party that would come to perpetrate the Holocaust and related crimes against humanity during World War II, but rather economics. As Sebald has explained, “they experienced upward mobility in the 1930s, like so many Germans; my father finished the war as a captain. Fascism did away with the class system—as in France under Napoleon, and in stark contrast to Britain, where it dominates the army to this day.”

His father was a prisoner of war following V-E Day and returned to his family in 1947. However, Sebald, like other young Germans growing up in the years immediately following the collapse of Nazi Germany, did not have ready access to his parents’ roles in the war or their experiences during wartime. He saw photographs his father had taken in Eastern Europe, and he saw footage of concentration camp liberations at school, but as he never got the chance to discuss those materials at home or in the classroom. Sebald’s exploration of “what to do with it”—those images of German perpetration and the aftermath of World War II—might help to guide readers through his works of fiction.

Sebald didn’t start writing fiction until he was in his 40s, decades after he had begun teaching literature as a university lecturer in England. He died in a car accident in 2001 at the age of 57, having completed four novels and numerous other works of poetry and nonfiction essays. How do these texts help to tell a new history of postwar Germany?

Rethinking a Post-Holocaust World

Sebald’s novels are fragmentary, filled with lines of poetic free verse and images with unknown (or, at the very least, undisclosed) histories. In some ways experiments in literary flânerie, novels like The Rings of Saturn [Die Ringe des Saturen: Eine englische Wallfahrt] (1995) or Austerlitz (2001), allow us to follow the paths of characters with deep connections to the Holocaust and to the crimes perpetrated during World War II.

Sebald’s novels are fragmentary, filled with lines of poetic free verse and images with unknown (or, at the very least, undisclosed) histories. In some ways experiments in literary flânerie, novels like The Rings of Saturn [Die Ringe des Saturen: Eine englische Wallfahrt] (1995) or Austerlitz (2001), allow us to follow the paths of characters with deep connections to the Holocaust and to the crimes perpetrated during World War II.

But Sebald’s works largely resist classification. In some ways, his fiction represents a new way of approaching the “official culture of mourning and remembering” in Germany, which Sebald described as flawed.** Instead, his fiction asks the reader to question the ever-present relationship between fact and fiction as we approach materials from the past and consider their relationship to the present.

We cannot recommend Sebald’s novels enough. What’s so remarkable about his works? There is something ephemeral about the power of his writing and his ability to pinpoint—without ever actually pinpointing—the problematic relationship of historical violence and memory. Perhaps Susan Sontag explains it best. In a Times Literary Supplement in 2000, she was asked whether “literary greatness is still possible.” Her response? Sontag wrote simply and succinctly, “one of the few answers available to English-language readers is the work of W.G. Sebald.”

*Read the full New Yorker article here.

**Sebald quoted in a 2001 article in The Guardian.