Part of the joy of being an proper, democracy-protecting American is getting to tell people what to do. The founders told the prominent how to govern, Evangelists told their parishioners how to behave, Emerson told his readers to be self-reliant, and Theodore Roosevelt told the nation’s men to be manly (whatever that may mean). Yet out of these many, bloviating camps, few have been more dedicated or influential than those who told us to be sober.

“Temperance literature” in the United States has a long and irrevocable tradition. Beginning with orators and journalists, a sturdy moral and philosophical foundation was laid to oppose the evils and ills of alcohol. Temperance, of course, built up enough momentum and support that it finally won; the prohibition of alcohol was implemented in 1920. Thirteen years later, the ban was erased, and the victories of the waning movement were confined to the many dry counties across the country.

“Temperance literature” in the United States has a long and irrevocable tradition. Beginning with orators and journalists, a sturdy moral and philosophical foundation was laid to oppose the evils and ills of alcohol. Temperance, of course, built up enough momentum and support that it finally won; the prohibition of alcohol was implemented in 1920. Thirteen years later, the ban was erased, and the victories of the waning movement were confined to the many dry counties across the country.

Ernest Charrington was a prominent temperance editor, journalist, and leader of the Anti-Saloon League. Consuming alcohol, he said, was responsible for the “poisoning of the germ-body plasm, mind, conduct, and society.” Charrington, in 1920, was provided the occasion of writing a victory chronicle of the temperance movement, stretching from the earliest laws in the country to curtail alcohol consumption in the 1600s.

A severe, damning, and didactic tone prevailed in much of temperance writing. “If you have any wish to become a useful member of society, and worthy of the respect of the virtuous,” ran an 1849 anti-booze screed in Amelia Bloomer’s magazine, The Lily, “shun the wine cup.” This is the language of abstinence: there is no middle ground. Yet Bloomer’s paper is all the more remarkable for being the first periodical in the country, perhaps the West, to be run and executed by women. The Lily, though it started exclusively to advance the cause of temperance, would soon pivot to take on general feminist concerns, including suffrage, abolitionism, domestic violence, and equal pay for women.

Then there was the fiction. Entire stories became so obsessed with the matter that they became known as “temperance novels.” As much as 12 percent of novels published in the 1830s examined alcohol as a social evil, though none of them has proven aesthetically worthy to become a classic. The novel Franklin Evans, or the Inebriate, written in 1842, is best remembered not because of its content but because of its author: Walt Whitman. It concerned an upwardly mobile man who falls from his duty and responsibility through temptations of pleasure and alcohol. Whitman later dismissed it as a book written just for the money, a light project he claimed to have written in only three days. (He barely learned his lesson: just recently, a second, long-lost Whitman temperance novel was found serialized in an old newspaper, titled The Life and Adventures of Jack Engle.)

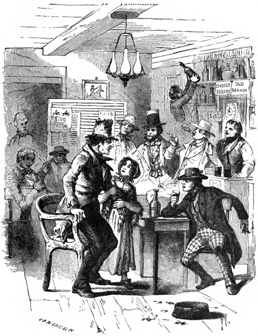

No work had gone as far as Timothy Shay Arthur’s Ten Nights in a Bar-Room and What I Saw There. Written in 1854, the book is pure melodrama. It follows a miller as he opens a tavern as a more profitable line of work. Inside, the narrator watches a once respectable man become the town alcoholic, his family torn apart trying to wrench him from the barstool. In one episode, his daughter is hit by a thrown glass which sends her to her death bed. The scene only devolves from there, as drunkenness leads to communal violence and mayhem, ending when the tavern owner’s son kills him in a fight. There was nothing, the novel contested, that alcohol could not ruin.

No work had gone as far as Timothy Shay Arthur’s Ten Nights in a Bar-Room and What I Saw There. Written in 1854, the book is pure melodrama. It follows a miller as he opens a tavern as a more profitable line of work. Inside, the narrator watches a once respectable man become the town alcoholic, his family torn apart trying to wrench him from the barstool. In one episode, his daughter is hit by a thrown glass which sends her to her death bed. The scene only devolves from there, as drunkenness leads to communal violence and mayhem, ending when the tavern owner’s son kills him in a fight. There was nothing, the novel contested, that alcohol could not ruin.

Yet perhaps what makes the cause of temperance most significant is that it provided citizens, namely women, with the means to organize and enact social change. Their allegiance to temperance made sense; after all it was women who had to endure the ravages of alcoholism as husbands turned impoverished, negligent, and abusive. Indeed, temperance helped provide women like Amelia Bloomer, Carrie Nation, and Frances Harper with a collective activist infrastructure that was turned to general social-justice causes like poverty, female suffrage, and abolition. We know how some of those fights ended.

In America, we may be annoyed at first by those who tell us what to do, but often it is the best of them who wind up improving us.