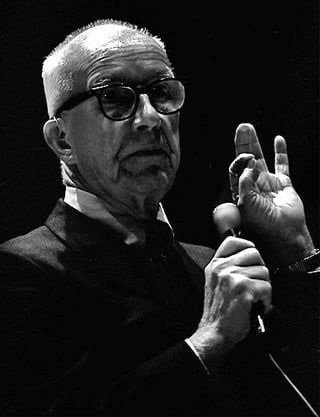

Who was R. Buckminster Fuller? In Stanford University Library’s description of the R. Buckminster Fuller Collection, the description describes Fuller as a “20th century polymath,” while the Buckminster Fuller Institute describes the man as “a 20th century inventor and visionary who did not limit himself to one field but worked as a ‘comprehensive anticipatory design scientist’ to solve global problems.” He was, indeed, a person of many interests, many academic pursuits, and many talents. Fuller lived through most of the twentieth century and published novels and essays, wrote poetry, designed architectural geodesic domes and works of contemporary art, and built prototype cars of the future.

His books are highly collectible, and if you are interested in seeing and learning more, you can access the R. Buckminster Fuller Collection at Stanford’s Special Collections and University Archives.

Fuller’s Life and Work

Before we get into talking in more detail about the Collection at Stanford, we want to say a bit more about Fuller’s early life and work. He was born in Milton, Massachusetts in 1895, and began attending Harvard University in 1913. Expelled twice, Fuller never returned to Harvard and later enlisted in the U.S. Navy Reserve. He married Anne Hewlett, the daughter of a New York architect, with whom he had a daughter. Fuller’s daughter later contracted meningitis and died in 1922. According to Stanford’s biographical timeline, by 1927, Fuller “consider[ed] himself a complete failure” and “seriously contemplate[d] taking his life.” However, he threw himself into his work instead, and in the late 1920s began some of his most important early studies.

By the early 1930s, Fuller had built the first prototype Dymaxion Car, which was later exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair. In 1938, he published his novel Nine Chains to the Moon. In the late 1940s, he began teaching at Black Mountain College and at the same time, he developed the geodesic dome. Through the rest of his life, Fuller continued writing, taught poetry at Harvard, and continued to develop designs for geodesic domes. He died in Los Angeles, California in 1983. From his early life onward, friends, family, and colleagues knew him primarily by the nickname “Bucky.”

Learning More About Stanford’s Fuller Collection

What can you expect to find in the Collection at Stanford? The archive is an expansive one. It contains Fuller’s personal archive, as well as manuscripts, drawings, correspondence, and audio-visual materials. Part of the collection has been digitized, which makes access easier for researchers. In total, the collection is 1200 linear feet.

If you’re interested in learning more about Fuller’s travels and dinner parties, you’ve come to the right place. If you’re interested in learning more about Fuller’s speaking engagements and professional life, the collection also contains these materials. And for collectors of Fuller’s books, papers, and ephemera, you can access manuscript drafts and other documents that may help to elucidate information about items in your own collection.

Most interesting, perhaps, is that visitors to the collection can explore the “Chronofile Index,” which represents Fuller’s organization of the collection.” Fuller organized his own archive? Indeed, he did. As the Collection Overview explains, “this collection was intended by Fuller to be used as a research tool,” given that “he saw his life as a grand experiment, the results of which had to be recorded.”

If you’re interested in learning more, you should take a look at the slideshow of the collection and then plan a visit out to Palo Alto, California for an in-depth look at R. Buckminster Fuller’s life and work.