For those of you who believe that climate change is the most significant threat facing the world right now, Rachel Carson should be your patron saint. A noted nature writer and a marine biologist by trade, Carson helped to usher in the modern environmentalist movement with her 1962 book Silent Spring, an indictment of pesticide overuse that is at once scathing and deeply unsettling to read. More than 50 years after her death, the deeply-held concern over the fate of the planet that she so scorchingly exemplified is a more powerful (and arguably much more urgent) force than ever.

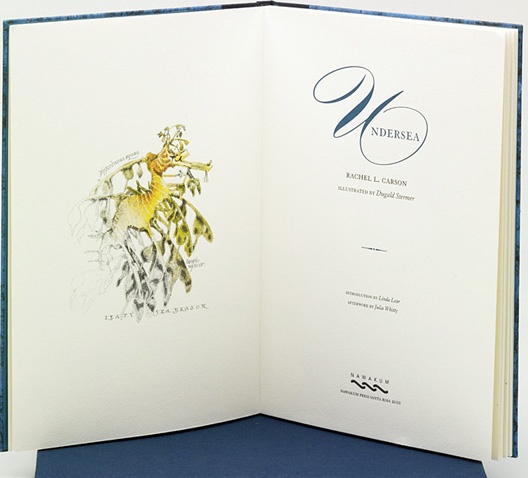

Rachel Carson studied biology at Chatham University and Johns Hopkins, and early in her career, she took a post at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (later known as the Fish and Wildlife Service), where her reputation as a gifted science writer began to take root. Her essay, 'Undersea' appeared in The Atlantic in 1937, and her much-loved first book, Under the Sea Wind was eventually published in 1941. Under the Sea Wind sought to give a vivid (and biologically accurate) narrative treatment to the lives of sea creatures. Though a compelling prose style and a sense of story are hardly givens for individuals with scientific training, projects like Under the Sea Wind and its sequels, The Sea Around Us (1951) and The Edge of the Sea (1955), found Carson firmly in her element, no doubt because of the abiding literary interests that she had fostered since childhood.

Rachel Carson studied biology at Chatham University and Johns Hopkins, and early in her career, she took a post at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (later known as the Fish and Wildlife Service), where her reputation as a gifted science writer began to take root. Her essay, 'Undersea' appeared in The Atlantic in 1937, and her much-loved first book, Under the Sea Wind was eventually published in 1941. Under the Sea Wind sought to give a vivid (and biologically accurate) narrative treatment to the lives of sea creatures. Though a compelling prose style and a sense of story are hardly givens for individuals with scientific training, projects like Under the Sea Wind and its sequels, The Sea Around Us (1951) and The Edge of the Sea (1955), found Carson firmly in her element, no doubt because of the abiding literary interests that she had fostered since childhood.

Indeed, at age 10 Carson was publishing children’s stories in national magazines. Entering college, her plan had been to major in English, spurred on by the love she had developed in high school for the likes of Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad, and Robert Louis Stevenson. When she switched her focus to biology, those literary instincts didn’t fade. While the dominant narrative of Carson’s life revolves around her fervent dedication to her scientific pursuits, a secondary narrative could easily be woven around the idea of blending the scientific with the literary in pursuit of works, like Silent Spring, that are not only scientifically sound but emotionally compelling.

Seen through this lens, it’s easy to understand the tremendous impact the book had and continues to have. By giving a literary treatment to the use of DDT to regulate mosquitoes for farming purpose—depicting with great intensity the crippling environmental effects of the deadly chemicals—she helped to motivate a movement that would work to discontinue DDT’s use for farming in the United States (the chemical, which targets mosquitoes, saw continued usage for malaria-management in other parts of the world), not to mention the creation—under the Nixon administration—of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Seen through this lens, it’s easy to understand the tremendous impact the book had and continues to have. By giving a literary treatment to the use of DDT to regulate mosquitoes for farming purpose—depicting with great intensity the crippling environmental effects of the deadly chemicals—she helped to motivate a movement that would work to discontinue DDT’s use for farming in the United States (the chemical, which targets mosquitoes, saw continued usage for malaria-management in other parts of the world), not to mention the creation—under the Nixon administration—of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Though Carson herself, who died of complications related to breast cancer in 1964, would not live to see most of the palpable effects of her work, she was privy to the controversy surrounding its initial publication in which she was painted as a fanatic—and was even speculated to be a communist, because she was attractive but unwed. But while remnants and echoes of the controversy persist in the present day—with an Oklahoma Senator blocking a commemoration of her 100 birthday as recently as 2007 on account of her ”junk science” unfairly demonizing DDT—so does the legacy of Rachel Carson’s work, spurring on environmental activists the world over.