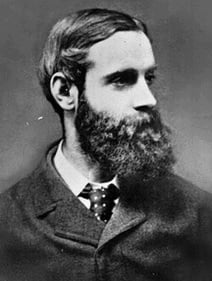

We all know the name, but few know the person. Behind the Caldecott Medal is the legacy of a man named Randolph Caldecott, born in England in 1846. By the end of his life he was a world-famous illustrator whose work sold in the hundreds of thousands. Children loved his drawings, especially adoring the color and energy of his work. Today, the Caldecott Medal honors illustrators who bring joy to children with stories, just as Randolph did 150 years ago. Yet the Caldecott Medal also commemorates what we have been deprived of—Randolph Caldecott had a too-brief career, passing away at the age of only 39.

Few would condemn Caldecott for failing to pack a full life into his short years, however. A childhood of tragedy and adversity made him sensitive to the importance of play, activity, and creativity. He began drawing as his mother died when he was only six. His own health problems—a heart damaged by a severe rheumatic fever—were present for his entire life. But he did not let his sickness impede him any more than it needed to. He was an active child who enjoyed walking through the country, and he was admired by his teachers. In adulthood, he used his sensitive health as an excuse to travel to different and warmer parts and see the world.

Few would condemn Caldecott for failing to pack a full life into his short years, however. A childhood of tragedy and adversity made him sensitive to the importance of play, activity, and creativity. He began drawing as his mother died when he was only six. His own health problems—a heart damaged by a severe rheumatic fever—were present for his entire life. But he did not let his sickness impede him any more than it needed to. He was an active child who enjoyed walking through the country, and he was admired by his teachers. In adulthood, he used his sensitive health as an excuse to travel to different and warmer parts and see the world.

Caldecott’s first job was as a bank clerk in his hometown of Chester. It was very important to his father that his sickly son found means to support himself. But his day job did not deter him from his true vocation.

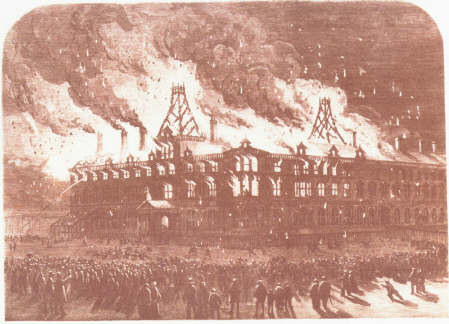

Caldecott’s first gig came unexpectedly. It was 1861, and the The Queens Railway Hotel had caught fire nearby his home. Caldecott rushed to the scene, perhaps by dogcart, as soon as he heard the news. At the site of the blaze, he composed his eyewitness sketch of the immolated building, its glow casting the vast crowd of bystanders in silhouette. Caldecott then took his rough sketch to make a precise illustration. He then sent it by rail to London, where skilled engravers would copy it to impress it in the newspaper. His drawing was featured in the Illustrated London News where it was seen by some 200,000 readers.

|

| Queens Hotel Fire, by Randolph Caldecott* |

It was a frantic, and rewarding, episode. It was all at once chaotic, exciting, and probably a fun adventure for the budding illustrator, who was only 15 years old at the time. In hindsight, it was a suitable introduction for an artist who would make his career creating dynamic and energetic images for a wide-eyed audience. He had found his viewers and his niche, but he was still anonymous. For all his work, the newspaper failed to credit him as an illustrator.

Caldecott’s big break would come later, around 1873, when he illustrated Washington Irving’s stories. He had moved to London the previous year to take his career as an artist seriously. There, he met and befriended talented contemporaries like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais. Entrenching himself further in the English art scene of his time, he spent time in the studios of friends, branching out to other forms like oil painting and clay sculpture.

Caldecott’s big break would come later, around 1873, when he illustrated Washington Irving’s stories. He had moved to London the previous year to take his career as an artist seriously. There, he met and befriended talented contemporaries like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais. Entrenching himself further in the English art scene of his time, he spent time in the studios of friends, branching out to other forms like oil painting and clay sculpture.

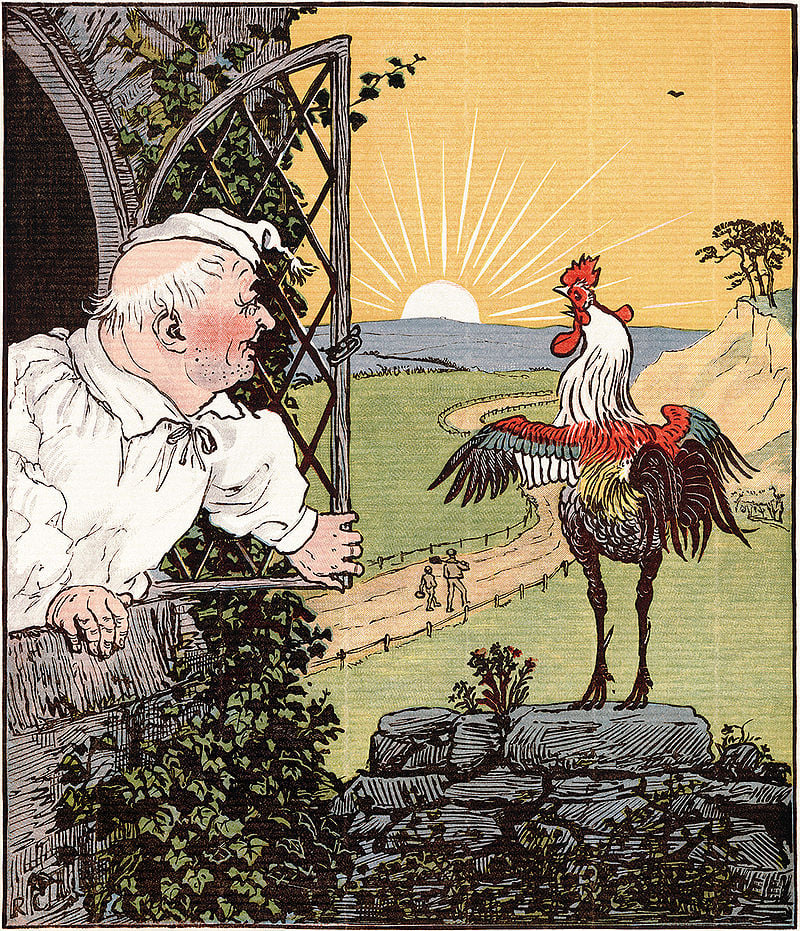

Still, magazine and book illustration remained Caldecott’s preferred medium. In his heyday, he illustrated two books for Christmastime for eight years straight. His two most significant books were children’s books, entitled The House that Jack Built and The Diverting History of John Gilpin. Both exhibit his exuberant and dynamic style. His illustration of John Gilpin, riding through town on a frantic horse, serves as the impression on the Caldecott Medal and is one his most exemplary works.

Randolph Caldecott may have had a brief life, but his work sets him among Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane as the best children’s illustrators of his time. By remembering his work and art, we make sure children will be introduced to the magic of books for generations to come.

*Image source.