In February, the New York Post discovered Harper Lee had been keeping a Manhattan apartment for ten years. She renewed the lease on the enviable, $900-per-month Upper East Side dwelling just a few months prior to her death. Her neighbors remembered her fondly, noting her love of Sunday crosswords. The local butcher too recalled her kind requests for select cuts of meat. Lee had not visited the apartment since her stroke in 2007, but it is remarkable how this secret had been preserved until the very end. Especially when one considers the public appetite for all things Harper Lee.

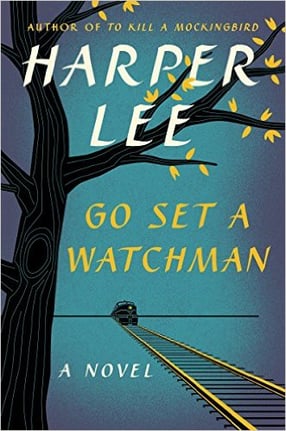

It’s to this very appetite that we owe the release of her final novel, Go Set a Watchman. Published in July of 2015, we now know that Watchman was indeed the first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, rather than the “sequel” it was marketed as. Yet whether the book itself is a work of high literary quality, or is an artifact for scholars and die-hard Mockingbird fans, is hard to say. One thing is certain, though, and it’s that Go Set a Watchman was a blockbuster event in the world of books.

It’s to this very appetite that we owe the release of her final novel, Go Set a Watchman. Published in July of 2015, we now know that Watchman was indeed the first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, rather than the “sequel” it was marketed as. Yet whether the book itself is a work of high literary quality, or is an artifact for scholars and die-hard Mockingbird fans, is hard to say. One thing is certain, though, and it’s that Go Set a Watchman was a blockbuster event in the world of books.

Go Set a Watchman’s sales saw astonishing numbers, setting records at Barnes & Noble and reaching Harry Potter-like heights at Amazon. That Harper Lee had not published a book in fifty-five years did not hurt her appeal. Her reclusion and reluctance to make public appearances only fanned the fires of rumor and enthusiasm.

Books Tell You Why wrote about the novel’s release last summer. At the time of writing, it wasn’t exactly clear where the text came from. The publicity machine kept it ambiguous, preferring that we believe Lee wrote it separately from Mockingbird, but abandoned it for a mysterious reason. This wasn’t the case, and it is now well-known that Go Set a Watchman was decidedly the classic novel’s first draft.

Go Set a Watchman was Lee’s first effort at a novel, and the book was revised closely over two years under the aegis of editor Tay Hohoff. There is said to have been talk between Hohoff and Lee to make a trilogy of sorts, with a connecting novel in between Mockingbird and Watchman. But that has been disputed. Rather, Watchman proved the stepping stone to Lee's magnum opus. In providing flashbacks to Scout’s youth within the larger story, it gave Lee and her editor a far stronger narrative environment to focus on.

It is hard to deny that prevailing opinion is set against Go Set a Watchman. This sentiment comes down to three principal reasons. The first is that Go Set a Watchman was never meant to be published. If it was fit for release, the publishers at Lippincott could have done so when they purchased the manuscript in 1957. Instead, they decided to work with its author, who displayed amazing potential but needed some development before finding an audience. The second reason is that Go Set a Watchman tramples on the narrative and aesthetic achievements of To Kill a Mockingbird. Complaints about Atticus Finch made many headlines during its release. Indeed, many were displeased to see one of literature’s most admirable figures fall victim to the same prejudices he fought against in the superior novel.

And the third, and final reason, is the suspicion that the book was a cash-grab, done at the expense of Harper Lee’s reputation and will. It was dubious that an author who refused to write any more books would suddenly publish something new a half century later. Some accusations declared elder abuse. It was also odd that the novel came out only a few months after Harper’s sister and lawyer, Alice, died. And, since a 2013 lawsuit on behalf of Lee, it had become apparent that people around the author were trying to exploit the ailing and elderly author’s declining capacities.

And the third, and final reason, is the suspicion that the book was a cash-grab, done at the expense of Harper Lee’s reputation and will. It was dubious that an author who refused to write any more books would suddenly publish something new a half century later. Some accusations declared elder abuse. It was also odd that the novel came out only a few months after Harper’s sister and lawyer, Alice, died. And, since a 2013 lawsuit on behalf of Lee, it had become apparent that people around the author were trying to exploit the ailing and elderly author’s declining capacities.

An official investigation was conducted, and found no evidence of elder abuse. Yet separate accounts, including one by Harper Lee’s neighbor and biographer, said that Lee was nearly blind and deaf and would sign anything that someone she trusted put in front of her. And, on top of the extra-textual doubt, reviewers were typically hostile to Go Set a Watchman. Critics from various publications declared the novel juvenalia, a cliche-ridden first draft, and a chore to read.

Others, like author Ursula K. Le Guin, gave credit to the book for dealing with matters that To Kill a Mockingbird shied away from. Among them were the book’s treatment of the matters of family, loyalty, equality, and love. In Watchman, Atticus is not a moral compass of the community anymore, but an encumbrance for the protagonist who becomes torn between family and morality.

The controversies that surrounded Go Set a Watchman upon its release are now better-settled by evidence. The novel was indeed a first draft, and was not likely endorsed by an author in her right state of mind, if at all. But the release of Watchman marked a significant moment in contemporary literary culture. That is, people got excited, outraged, and interested in this peculiar saga. Opinions were shared, books flew off the shelves, and people were inspired to read. Now who’s to say that’s such a bad thing?