On the whole, the term Chicano describes the culture of a people who live within the mixing currents of Mexican and American life. Other than that, the Chicano identity is predictably hard to pin down. Nonetheless, writers of the Chicano tradition have played a vital role in giving a voice to a people who have not easily found one. The Chicano tradition is notably vast and hybridized, coming from two already diverse nations. While there have been Mexican-American writers since the age of exploration, Chicano culture truly came into being after the Mexican American War, when many Mexicans found their home suddenly under the red, white, and blue flag. Since its inception, Chicano literature has helped an entire culture forge its identity by letting its stories be told. Today, we'd like to explore some of voices of the Chicano literary tradition.

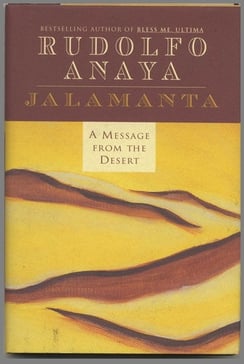

Rudolfo Anaya

Anaya is one of today’s most prominent Chicano authors. His work helped introduce the culture’s literature to the mainstream. His book, Bless Me, Ultima, is featured on high school syllabi across the country; however, Anaya was not embraced by American readers overnight.

Anaya is one of today’s most prominent Chicano authors. His work helped introduce the culture’s literature to the mainstream. His book, Bless Me, Ultima, is featured on high school syllabi across the country; however, Anaya was not embraced by American readers overnight.

Anaya’s books faced a good deal of rejection. Publishers initially didn’t know what to make of its subject matter and its occasional use of the Spanish-language. Many editors dismissed it on the basis of it being unlikely to find an adequate market. This alienation mirrored that which Anaya felt as an undergraduate at the University of New Mexico. At school, he enjoyed his classes, but found himself to be the only Chicano student around.

Soon enough, Anaya was swept up in the Chicano Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. He was invigorated by the assertion that the story of his culture deserved to be told, and he began composing the stories that he identified with, drawing upon the memories of his elders and the New Mexico village of his upbringing.

Oscar “Zeta” Acosta

Acosta’s work is the most virulently political of all on this list. In addition to being a writer, Acosta was also an attorney, offering legal protection for the causes and people of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. He wrote two books that were considerably autobiographical: The Revolt of the Cockroach People, which fictionalizes the fraught Chicano protest of the Vietnam War, and Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, which introduces an alienated lawyer who works on behalf of the poor and disenfranchised.

Acosta also became friends with Hunter S. Thompson, who fashioned a character from Acosta’s likeness in his novel, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Thompson initially connected to the Chicano writer because of a piece he wrote in Rolling Stone in 1971 about injustice in Hispanic communities in East L.A.. Acosta disappeared in Mexico in 1974 under mysterious circumstances, and is presumed dead.

Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton

Burton, born in 1832, actually lived through the annexation of Mexican territory following the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. She also married a United States general who served in the Mexican-American War and fought for the Union during the Civil War. She traveled with him around the U.S., to wherever he was posted, including Virginia, Delaware, and Rhode Island. Brought into the spheres of the elite, Burton befriended the likes of Mary Todd Lincoln. For this reason, Burton’s fiction is endowed with the critically sharp perspective of an outsider.

Burton, born in 1832, actually lived through the annexation of Mexican territory following the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. She also married a United States general who served in the Mexican-American War and fought for the Union during the Civil War. She traveled with him around the U.S., to wherever he was posted, including Virginia, Delaware, and Rhode Island. Brought into the spheres of the elite, Burton befriended the likes of Mary Todd Lincoln. For this reason, Burton’s fiction is endowed with the critically sharp perspective of an outsider.

Her fiction, such as her novel, Who Would Have Thought? (1872), examines American attitudes, especially those of elite Northeasterners. Her exploration of the way in which cultural lines divide America — the ways in which Mexicans, women, and outsiders are marginalized — anticipated one of Chicano literature’s most significant concerns. Burton is often called the first Mexican-American writer.

These are but a few of the many worthy Chicano writers who have helped to forge the identity of a culture in their work. And what better way to do this, in the end, than by telling one's own story?