We all know that it’s big, important, and crucial to our culture. After that, the details get vague. The truth is that the Library of Congress has a fascinating history, as well as a pretty cool present, and we’d like you to be as informed about the library as those that use it are about the world we live in. Read on to find out how the Library of Congress became the library of the people, and how it literally rose from the ashes and became an institutional gem in our nation’s history.

1. The Original Library Was Burned to the Ground

1. The Original Library Was Burned to the Ground

Fourteen short years after it was founded—only to be populated with books and materials for members of Congress—British troops burned the entire building and all of its contents to the ground. President Thomas Jefferson came to the rescue, proving his own library, a work of over 50 years of collecting, as a replacement. Unlike the original library, the new one contained all sorts of materials, to which Jefferson remarked, “I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer."

2. The Library Grew Due to Copyright Law

Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the Librarian of Congress who had formerly worked in newspapers, was aware that acquiring books and materials for the library would become a strain on the budget and perhaps a detriment to the growth of the library. He took a page out of the book of England and France and made the Library of Congress a centralized copyright agency, which required each published book or pamphlet to send the library two free copies of the work in order to acquire copyright status.

3. The Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Had Some Growing Pains

There were two institutions, the Library and the Museum. At some point, in the 1850s, there was a push to make them one and the same. The Smithsonian had its own librarian, Charles Coffin Jewett, and he felt that there should be no separation and that the two should become one and create a national bibliographical center. The plan was thwarted early, however, by Smithsonian secretary Joseph Henry who felt that the two institutions had vastly different jobs and purposes and that the Smithsonian should concentrate on scientific research and publication. Eventually Jewett was dismissed by Henry, and a few years later, he sent the remaining print collection still held by the Smithsonian over to the Library of Congress permanently.

4. The Library of Congress Houses the Largest Publicly Available Collection of Comic Books in the United States

With over 6,000 titles and more than 100,000 issues, the Library of Congress is able to brag the ownership of the largest comic book collection in the United States. The collection begins with the introduction to printed comic books in the 1930s to current releases and foreign titles. Though a majority of the collection is built due to copyright acquisition, the library also has made efforts to actively collect and uses the criteria of quality, artist significance, popularity, and circulation statistics to collect outside of copyright. The library also seeks out self-published and experimental titles in hopes of new artists bearing future cultural significance.

5. The Library Functions for the Government to Learn

The library is a massive collection and is open to the public. However, from its beginning the central purpose, prescribed by Jefferson, was that the government could only be effective if it had a comprehensive knowledge base of information. Above and beyond the basic understanding of the government’s function, those that serve must be culturally aware and the library was created and continues to be funded to that end. There is a single department, the Congressional Research Service (CRS), that exists solely to help those in Congress access and understand materials that will help them do their jobs properly and remain informed on all subjects. They stay busy with over 500,000 research requests every year.

6. When It Come to Primary Sources, The Library of Congress Is the Place To Be for Old Stuff

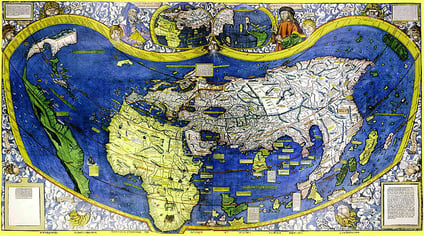

For instance, there are three Gutenberg Bibles in the entire world. The Library of Congress has one of them. In addition, they house a Sumerian cuneiform tablet, which dating back to 2040 b.c., is the oldest piece of known written material. That’s right, the first time someone wrote something down and we kept it, the Library of Congress has that. They also have the first time we captured moving pictures on film and kept it, Fred Ott’s Sneeze, copyrighted in 1893 by Thomas Edison. If you’re wondering what it was like being a slave in the south before the Civil War, the Library of Congress website holds audio recordings of slave narratives collected in the 1930s. Marquis de Lafayette’s personal, political, and military papers which had been thought inaccessible and housed in a castle in France were aquired by the Library of Congress in the mid 1990s. Finally (but not really) there is a single copy of the 1507 Waldseemüller world map, considered America’s birth certificate, and it lives on permanent display in the Library of Congress. For the oldest, the coolest, and best...the Library of Congress does the job of serving future generations and current researchers.

For instance, there are three Gutenberg Bibles in the entire world. The Library of Congress has one of them. In addition, they house a Sumerian cuneiform tablet, which dating back to 2040 b.c., is the oldest piece of known written material. That’s right, the first time someone wrote something down and we kept it, the Library of Congress has that. They also have the first time we captured moving pictures on film and kept it, Fred Ott’s Sneeze, copyrighted in 1893 by Thomas Edison. If you’re wondering what it was like being a slave in the south before the Civil War, the Library of Congress website holds audio recordings of slave narratives collected in the 1930s. Marquis de Lafayette’s personal, political, and military papers which had been thought inaccessible and housed in a castle in France were aquired by the Library of Congress in the mid 1990s. Finally (but not really) there is a single copy of the 1507 Waldseemüller world map, considered America’s birth certificate, and it lives on permanent display in the Library of Congress. For the oldest, the coolest, and best...the Library of Congress does the job of serving future generations and current researchers.

Citations:

-History of the Library. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2016, here.

-John Y. Cole (2010, September 7). A History of the Library of Congress [Web log comment]. Retrieved here.

-Library of Congress established. (2010). Retrieved March 30, 2016, here.

-Library of Congress. (2016, March 29). Retrieved March 30, 2016, here.

-Comic Book Collection. (2013, April). Retrieved March 30, 2016, here.

-Highsmith, C. M. (n.d.). Main Reading Room [Photograph found in The Main Reading Room, Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, Washington, D.C.]. Retrieved March 30, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 2008, December 13)

-Waldseemüller world map [Photograph]. (2009, February 14). Minnesota Geological Survey, University of Minnesota.

-Trumbull, J. (n.d.). Thomas Jefferson by John Trumbull 1788 [Photograph found in The White House Historical Association]. Retrieved March 30, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 1787, December 31)