On August 9, 1854, Henry David Thoreau published his book, Walden; or, Life in the Woods. It narrates—with an ample serving of artistic intervention—its author’s experiment to live divorced from society, in an effort to uncover better ways of living. “I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life,” he writes in a manifesto-like paragraph of Walden, “to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.”

Even in such a brief passage, one can observe the rapturous prose and vigor of perception that Thoreau imbues his writing with. Let’s take the book’s anniversary as occasion to reflect on a few details you might not know about this transcendentalist classic.

Even in such a brief passage, one can observe the rapturous prose and vigor of perception that Thoreau imbues his writing with. Let’s take the book’s anniversary as occasion to reflect on a few details you might not know about this transcendentalist classic.

It was published under one of history’s least inventive pseudonyms

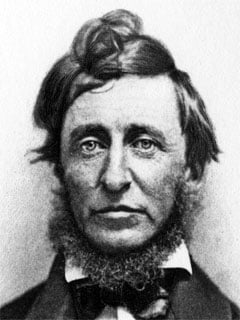

Henry David Thoreau was actually born David Henry Thoreau. See the distinction? It’s not certain why the name-change made much of a difference to him, and all we’re left to do is make inferences based on character. (Perhaps his priority for self-reliance compelled him to have control over his name, but that, like anything, is guesswork.)

The land was owned by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Thoreau’s friend and mentor owned the woodland on Walden Pond where the author was to live and write for over two years. The pair arranged a sort of friendly trade: Thoreau was permitted to build his house on the property, and Emerson was repaid by Thoreau’s labor in efforts like clearing the land. Thoreau, who was not financially well-off at the time, benefited from the aid of friends and family during his tenure at Walden Pond.

Thoreau wasn’t exactly “roughing it”

As is a favorite point of Thoreau’s critics, the wild life he lived was rather tame. His mother famously helped him out with laundry and food over the two years, and he had guests over regularly. And the land itself was not the rugged frontier. “In reality,” writes Kathryn Schulz in the New Yorker, “Walden Pond in 1845 was scarcely more off the grid, relative to contemporaneous society, than Prospect Park is today. The commuter train to Boston ran along its southwest side; in summer the place swarmed with picnickers and swimmers, while in winter it was frequented by ice cutters and skaters.” She adds that it would take Thoreau but twenty minutes to walk from his cabin to his family home, were we to confuse the writer with Robinson Crusoe.

Writing the book took longer than his stay at the cabin

In the book, Thoreau presents the narrative within the time frame of a year. His actual stay, however, was a little over two years and two months. It took nearly ten years to write and to publish Walden, which was written and still reads like a collection of essays, on subjects as varying as “Economy,” “Sounds,” and working in a bean field.

Walden was published to a mild reception.

The book had a print run of 2,000 copies, which took five years to sell out. His friends, like Emerson, advocated for his work, which helped his book become the classic it is today. While not impressive, such a sales figure was by no means unusual in the American nineteenth century, which had a way of being rather unreliable to the writer. By comparison, Leaves of Grass’ first print run sold only about 795 copies, while great writers like Herman Melville died with heavy debts and little acclaim.

The book had a print run of 2,000 copies, which took five years to sell out. His friends, like Emerson, advocated for his work, which helped his book become the classic it is today. While not impressive, such a sales figure was by no means unusual in the American nineteenth century, which had a way of being rather unreliable to the writer. By comparison, Leaves of Grass’ first print run sold only about 795 copies, while great writers like Herman Melville died with heavy debts and little acclaim.

Its author is having a hot moment right now

Spurred by an anti-Thoreau essay* in the New Yorker about nine months back, the author of Walden has been having his legacy and reputation vigorously argued over. Kathryn Shulz, writer of the New Yorker piece, considers Thoreau’s writing adolescent, misanthropic, presumptuous, and selfish. She frames her argument like a voice of radical dissent, but readers have been leveling against Thoreau’s value for a while. It was Garrison Keillor who said Thoreau was:

A sorehead and loner whose clunky line about marching to your own drummer has found its way into a million graduation speeches. Thoreau tried to make a virtue out of lack of rhythm. He said that the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. Okay, but how did he know? He didn’t talk to that many people. He wrote elegantly about independence and forgot to thank his mom for doing his laundry.

Indeed, Thoreau’s legacy is not at its strongest. His name is eroding from classroom syllabi, and while his influences encompass the likes of Tolstoy, Proust, and Dickinson, his partisans seem much rarer today.

Many, such as Donovan Hohn**, argue that we have gone far enough in resisting and lampooning Thoreau. Instead, we should return to him (both sides, pro and contra, agree that Thoreau is sooner evaluated than read) and appreciate his first-rate prose, his questions about a life well-lived, and his reflections on nature and the environment, which in the era of climate change, are as vital to us now as they have ever been.

*Read the full essay here.

**Read Donovan Hohn's perspective here.