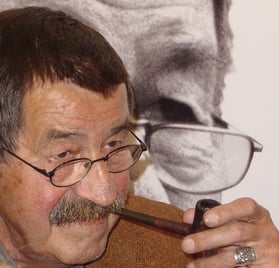

Günter Grass, who won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature, died earlier this year, at the age of 87. He maintained a complicated attitude toward the country of Germany for all his life. Grass was a true agitator; he was almost always political, polemical, and provocative. Consequently, upon his death many obituaries concerned themselves with his political controversies, of which there were certainly a good deal. But of course, Grass was a multifaceted person and artist. On the 88th anniversary of his birth, we peel back the divisive persona, and take a look at the legacy of Günter Grass.

Grass Was a Visual Artist

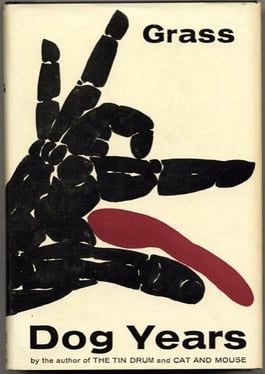

Grass went to art school, and remained a practicing sculptor and sketch artist for his entire life. He gained certain insights about writing from the act of sculpting, such as the need to keep all parts of a manuscript moldable and raw for future improvements. He was always involved in designing the cover of his books, and often produced original work for them. His art, such as that featured in his novel The Flounder, ventures into the absurd and obscene (for that, we’ll let you do the research).

Grass went to art school, and remained a practicing sculptor and sketch artist for his entire life. He gained certain insights about writing from the act of sculpting, such as the need to keep all parts of a manuscript moldable and raw for future improvements. He was always involved in designing the cover of his books, and often produced original work for them. His art, such as that featured in his novel The Flounder, ventures into the absurd and obscene (for that, we’ll let you do the research).

He Might Have Lied About Meeting the Pope

In the twilight of World War II, Günter Grass was a prisoner of war. Under United States captivity, he claimed that he befriended William Ratzinger, who went on to become Pope Benedict XVI. Grass recalled that the two talked about their future plans. He professed plans to be an artist, and Ratzinger intended to go into the church. In addition, Grass claimed that the pair rolled dice together, and described his companion as “extremely Catholic,” “a little uptight,” and “a nice guy.” Vatican sources, however, denied this “nice invented story,” insisting that Ratzinger has too sharp a memory not to have mentioned knowing Grass anywhere before.

Grass’ The Tin Drum Was a Major Contribution to the Style of Magical Realism

His most famous book, The Tin Drum (1959), was released to mixed reviews. Some considered it obscene and blasphemous. Overall, Grass was interested in uncovering what about the German character enabled so many to ignore the odious actions of the Third Reich. The book’s integration of folk culture, myth, and allegory make it a significant work of magical realism in Europe. The style has also been employed by Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende, Alice Hoffmann, Jorge Luis Borges, and Salman Rushdie. Rushdie has admitted many times to the influence Grass has had on his work.

He Was Part of a Significant Literary Association in Postwar-Germany

Gruppe 47 (Group 47) was founded by German writers who were desperate to understand what was to be the fate of German letters. For many artists, the end of the Second World War was a significant time of discovery because many works that were banned by the Third Reich began to shuffle back into print. It was during this time that Grass discovered many of his most significant influences, such as Kafka, Camus, Döblin, and Faulkner.

A major preoccupation of Gruppe 47 was what should be done about the German language, which had been tainted by the rhetoric of the Nazis. Grass argued that “a language should not be punished because it was abused.” Gruppe 47 also counted writers like Heinrich Böll and Peter Weiss among its members.

Yes, He Was Controversial

Gruss opposed the reunification of East and West Germany at the end of the Cold War. He believed that a strong and centralized Germany had proven what terror it was capable of, and had forfeited the moral right to be unified. Grass tackled the issue of German unification in his novel Too Far Afield, comparing the fall of the Berlin Wall to the 1870-71 formation of the country under Otto von Bismarck. The fact that Grass preferred a fractured and divided nation felt like a betrayal to a good deal of Germans.

Gruss opposed the reunification of East and West Germany at the end of the Cold War. He believed that a strong and centralized Germany had proven what terror it was capable of, and had forfeited the moral right to be unified. Grass tackled the issue of German unification in his novel Too Far Afield, comparing the fall of the Berlin Wall to the 1870-71 formation of the country under Otto von Bismarck. The fact that Grass preferred a fractured and divided nation felt like a betrayal to a good deal of Germans.

He Concealed His Tenure in the Waffen-SS for Most of His Life

In his 2006 memoir, Peeling the Onion, Grass confessed to serving in the Waffen-SS for the final six months of the war, when he was 17 years of age. While he claimed that he never shot anyone, this news was received as outrageous and hypocritical. How could the man who dedicated his entire career to being Germany’s conscience in the aftermath of Nazism have fallen under its very spell? It was the most controversial moment of Grass’ career, one that still tarnishes his legacy to some.

Still, no one had revealed the truth of Grass’ Nazi service for the half-century of the author’s public life. Surely he had friends who knew, as well as fellow soldiers who would have recognized their famous comrade. And journalists, with some research, could have discovered the truth on their own. That people turned away from the truth reveals the very problem that Grass’ public and artistic work attempted to remedy: Germany often enough preferred to treat the shame of history with silence and ignorance. Whether voluntary or not, Grass’ life embodies the very difficulties that reckoning with a gruesome and troublesome past entails. This is one of many ways Günter Grass represented his Germany and aimed to make the world a better place today than it was yesterday.