1. He Was Friends with Henry David Thoreau...and Often Provoked Him

Though they were fourteen years apart, these two great minds enjoyed intellectual sparring with one another. Emerson’s sister-in-law introduced the two in 1837 when Thoreau was just 20 years old and Emerson was in his 30s. The two began conversing and taking walks in nature. Thoreau detested higher education, while Emerson embraced it, and would intentionally praise college in order to annoy Thoreau and create tension. Emerson admired Thoreau’s insistence on retreating to nature rather than indulging in the world and in higher academic versions of education. In Emerson’s journal it is written, “[Thoreau] chose wisely no doubt for himself to be the bachelor of thought & nature that he was— how near to the old monks in their ascetic religion! He had no talent for wealth, & knew how to be poor without the least hint of squalor or inelegance.”

Though they were fourteen years apart, these two great minds enjoyed intellectual sparring with one another. Emerson’s sister-in-law introduced the two in 1837 when Thoreau was just 20 years old and Emerson was in his 30s. The two began conversing and taking walks in nature. Thoreau detested higher education, while Emerson embraced it, and would intentionally praise college in order to annoy Thoreau and create tension. Emerson admired Thoreau’s insistence on retreating to nature rather than indulging in the world and in higher academic versions of education. In Emerson’s journal it is written, “[Thoreau] chose wisely no doubt for himself to be the bachelor of thought & nature that he was— how near to the old monks in their ascetic religion! He had no talent for wealth, & knew how to be poor without the least hint of squalor or inelegance.”

2. He Was an Ordained Unitarian Minister

Coming from a long line of clergy, Emerson continued the family tradition by studying the ministry and gaining license in 1826 and becoming ordained in 1829. When his beloved wife died of tuberculosis in 1831, he lost his faith and resigned from the clergy.

3. He Was a Known as "The Sage of Concord"

Though he lost his faith, he did not stop trying to find meaning, and he became a major name in the transcendentalist movement, even being known as “The Sage of Concord". His group, mainly composed of writers and artists, included Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, and W. E. Channing.

Transcendentalists believed that the individual could literally move into a spiritual plain of enlightenment by faith and force of will. He and others like him believed that God lived within their own being and could be interacted with directly. His first book, Nature, and the journal The Dial, which he was heavily involved in starting and maintaining, were focused on this subject.

4. He exposed American Thinkers to the Writings and Philosophies of Asia and the Middle East

He was fascinated—with varying levels of investment and intensity—with Asian and Middle-Eastern philosophy and culture, even nicknaming his second wife“Mine Asia”—a pun on Asia Minor. Having watched the harbor as a boy in Boston, Emerson was first introduced to the Indonesian-Chinese trade that was a staple of the docks after the Revolutionary War.

His father edited the Monthly Anthology, which reported on South Asia to New England, including bringing a translation of the Sanskrit play “Sakuntala, or the Fatal Ring.” He continued to invest and study Asia and the Middle East at Harvard which influenced his work, philosophies, and ideas about life. As he found and began to lecture on the ideas surrounding transcendentalism, he used the Indian, Persian, and Chinese texts to explore his new-found way of thinking and believing and shared these ideas in his lectures and in The Dial through “Ethnical Scriptures” showing the world that philosophies of truth were universal.

5. He Was a Boy Genius

Most of us spend our 14th year in junior high school, worrying about coming of age. Emerson, however, having flown through the Boston Latin School and having been recognized as a great mind and deeply encouraged by his educators, found himself the youngest member of his Harvard class at just 14. Instead of spending these formative years at awkward dances, he spent his studying great works. He graduated in 1821.

6. He Was Raised By Women

Though he followed his father into the clergy, Emerson was without him for most of his life. His father, Reverend William Emerson, died when Emerson was just shy of eight years old, and he was then raised by his mother and a series of aunts. Though he had three brothers, their universe was populated and led by strong female minds and voices. He and his family were invested in educating women, which was not a societal priority at the time, and his brother William went on to found a school for girls in the family home. Emerson was a teacher and director in that school for a time before going on to divinity school.

Though he followed his father into the clergy, Emerson was without him for most of his life. His father, Reverend William Emerson, died when Emerson was just shy of eight years old, and he was then raised by his mother and a series of aunts. Though he had three brothers, their universe was populated and led by strong female minds and voices. He and his family were invested in educating women, which was not a societal priority at the time, and his brother William went on to found a school for girls in the family home. Emerson was a teacher and director in that school for a time before going on to divinity school.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2016, here.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2016, here.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2016, here.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson's grave, Sleepy Hollow, Concord, Mass. [Photograph]. (n.d.). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

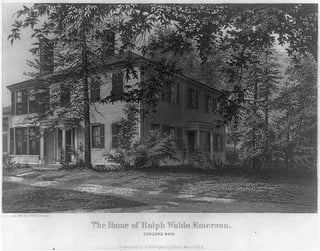

-The Home of Ralph Waldo Emerson [Photograph]. (n.d.). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right [Photograph]. (n.d.). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.