The Glass Menagerie narrowly avoided complete disaster when it premiered in Chicago in 1944 with the inebriated Laurette Taylor in the crucial role of overbearing matriarch, Amanda Wingfield. Taylor was found drunk in the alley behind the theater an hour and a half before the opening curtain. Somehow, despite needing to vomit in a bucket backstage between scenes, she managed to pull off a performance still considered legendary. It was this performance on which hung the destiny of one of America's greatest playwrights: Tennessee Williams.

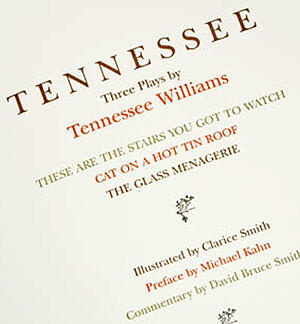

The play was a great success, giving Williams his first big break and winning the 1945 New York Drama Critics Award. It was followed in 1947 by the even more successful A Streetcar Named Desire, which opened on Broadway in the Ethel Barrymore Theatre and starred Marlon Brando and Jessica Tandy. Directed by Elia Kazan, Streetcar went on to win the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, which premiered in 1955, completed the trifecta of what Tennessee Williams would come to call, "The Catastrophe of Success" in a 1947 essay that appeared in the New York Times.

The play was a great success, giving Williams his first big break and winning the 1945 New York Drama Critics Award. It was followed in 1947 by the even more successful A Streetcar Named Desire, which opened on Broadway in the Ethel Barrymore Theatre and starred Marlon Brando and Jessica Tandy. Directed by Elia Kazan, Streetcar went on to win the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, which premiered in 1955, completed the trifecta of what Tennessee Williams would come to call, "The Catastrophe of Success" in a 1947 essay that appeared in the New York Times.

If Williams's success was self-described as the result of a catastrophe, his life up until The Glass Menagerie must also have played a role. Born on March 26, 1911 in Columbus, Mississippi as Thomas Lanier Williams, he was the middle child of Cornelius and Edwina Williams. His sister, Rose, was two years his senior; his brother, Dakin, was eight years his junior. Cornelius was abusive and an alcoholic who showed contempt for his effeminate middle child, going so far as to nickname him Miss Nancy. Edwina, who fancied herself a southern belle, was a high-handed, snobbish woman with a fear of sex. She passed on that fear to her children, a theme that would play out again and again in her famous son's plays. Williams wrestled with his own sexuality into his late twenties when he finally accepted his homosexuality.

The family moved to St. Louis, Missouri when Williams was eight. He attended the University of Missouri from 1929 until 1931, but didn't graduate. After failing ROTC, Cornelius Williams pulled him out of college and put him to work at the same company where he himself was employed, the International Shoe Company. Young Tom Williams hated the tediousness of the job, and he began to stay up until all hours of the night, fueled by coffee and cigarettes, to carve out time to pursue writing. His parents separated in the mid-1930s because of his father's escalating alcoholism and violence, and Williams was able to escape some of his father's tyranny. He enrolled in Washington University in St. Louis in 1936, and he eventually completed his education in 1938 with a B.A. in English from the University of Iowa. It was around 1939 that he adopted the name Tennessee Williams. It's unclear whether he took on the title as a nod to his Tennessee ancestors, or because it was a nickname given to him in college as a result of his thick southern accent.

Meanwhile, Williams's sister, Rose, with whom he was very close, was slipping slowly into madness. She was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia. When their mother, Edwina, could no longer tolerate Rose's mad ramblings, which were often lewd, she authorized the state hospital to give Rose a bilateral prefrontal lobotomy in 1943. The botched lobotomy left Rose debilitated, and she had to be institutionalized the rest of her life. Williams never forgave his mother for Rose's lobotomy, and his sister's sad fate haunted him until he died. Some aspect of Rose was written into a character in almost every play Williams wrote, but she is most famously immortalized as the character Laura Wingfield, nicknamed "Blue Roses," in The Glass Menagerie.

Meanwhile, Williams's sister, Rose, with whom he was very close, was slipping slowly into madness. She was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia. When their mother, Edwina, could no longer tolerate Rose's mad ramblings, which were often lewd, she authorized the state hospital to give Rose a bilateral prefrontal lobotomy in 1943. The botched lobotomy left Rose debilitated, and she had to be institutionalized the rest of her life. Williams never forgave his mother for Rose's lobotomy, and his sister's sad fate haunted him until he died. Some aspect of Rose was written into a character in almost every play Williams wrote, but she is most famously immortalized as the character Laura Wingfield, nicknamed "Blue Roses," in The Glass Menagerie.

The success of Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire allowed Williams to move Rose from a public institution into private care. He set up a trust to provide for her for the rest of her life. When she died in 1996, seven million dollars were still left in the trust and given, along with the rest of the Williams estate, to the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee.

Even though Williams's early life was filled with struggle and family turmoil, he believed it was a life that had made him an artist. In his 1947 New York Times essay "The Catastrophe of Success," he said:

"The sort of life that I had had previous to this popular success was one that required endurance, a life of clawing and scratching along a sheer surface and holding on tight with raw fingers to every inch of rock higher than the one caught hold of before, but it was a good life because it was the sort of life for which the human organism is created... Security is a kind of death, I think, and it can come to you in a storm of royalty checks beside a kidney-shaped pool in Beverly Hills or anywhere at all that is removed from the conditions that made you an artist, if that's what you are intended to be. Ask anyone who has experienced the kind of success I am talking about -- What good is it?"

Although the popularity of his plays in the 1940s and 1950s had insured his financial stability for the rest of his life, by the 1960s, his professional success began to wither away. Audiences and critics believed his best work was behind him. A Life magazine critic even wrote, "Other playwrights have progressed; Williams has suffered an infantile regression."

Williams's "regression" began with his first Broadway failure, The Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore, which premiered in the U.S. in January 1963. The Broadway flop was immediately followed by a huge emotional blow. Frank Merlo, Williams's partner of fourteen years, died on September 20, 1963 from inoperable lung cancer. Merlo's death plunged Williams into a terrible depression, which made him turn increasingly to drugs and alcohol. The combination made it difficult for him to work. He began a twenty-year downward spiral, cycling in and out of hospitals and mental health institutions. On February 25, 1983, Williams was found dead in his hotel room. The official medical examiner's report said that his death was caused by choking on a cap from a bottle of eye drops. However, his friends and colleagues suspected his death was actually the result of a drug overdose.