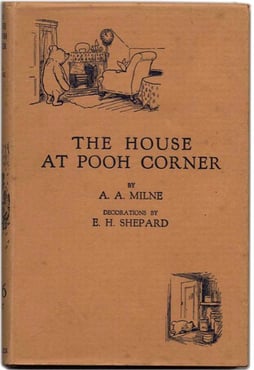

When writers began fighting for copyright protection around two hundred years ago, they were mostly trying to avoid getting ripped off by renegade printers. Sage as they were, not even the best of them could have predicted just how much money could be on the line. It’s unlikely that even A.A. Milne could have fathomed just how valuable his own intellectual property would become, in the forms of Winnie, Eeyore, Piglet, and the gang. Beginning as a children’s poem in the 1920s, Winnie-the-Pooh is now at the center of a merchandising and media empire that totals upwards of $5 billion a year.

Although ninety years old, there have since been few literary creations to establish a franchise like Winnie-the-Pooh. The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter come to mind, but examples are few and far between. When Stephen Slesinger purchased the rights to Winnie-the-Pooh in 1930, he inaugurated the licensing industry as we know it today.

Although ninety years old, there have since been few literary creations to establish a franchise like Winnie-the-Pooh. The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter come to mind, but examples are few and far between. When Stephen Slesinger purchased the rights to Winnie-the-Pooh in 1930, he inaugurated the licensing industry as we know it today.

Getting his start as a literary agent. Slesinger was a literary agent who represented the major children’s writers of his day, including a handful of Newbery Medal winners. But what distinguished him was his business acumen and desire for expansion. Slesinger would go on to succeed in the worlds of comic strips, film, radio, and further licensing, including Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan. Yet none of his projects would eclipse Winnie-the-Pooh, which, after fewer than two years, generated $50 million in annual revenue.

Slesinger eventually focused the majority of his energy on media production. His $10,000 investment in Milne’s world and characters seemed like a small price to pay. As television and film blossomed in the coming decades, Pooh found more and more outlets for income and exposure. The Hundred-Acre Wood and its cuddly inhabitants became increasingly beloved, recognizable, and most importantly, lucrative. It wouldn’t be long before this impressive empire would begin to attract a good deal of attention, and envy.

After Stephen Slesinger died in 1953, the rights to Winnie went to his wife, Shirley. It was in this period that a new institution began to assert itself as the next step in the valuable franchise’s future. In 1961, the Walt Disney corporation struck a deal with Ms. Slesinger, and five years later released its first film, Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree.

It was through Disney that Winnie became the truly global phenomenon that we know today. From a collection of stories published in 1926, a world famous cast of characters began to decorate innumerable goods, including backpacks, Band-Aids, strollers, and vitamins. It is perhaps no surprise then, that the original owners at Stephen Slesinger, Inc. began to look at this colossal success with a tinge of jealousy.

The original 1961 deal held that the Slesinger estate would sell the entirety of the licensing rights to Disney, while retaining a 2% share of the franchise’s annual revenue. A court case, brought up in 1983, allowed the former owners to take a brief repossession of the rights, to then redistribute them back to Disney. This odd legal maneuver set the stage for a 1991 litigation case in which the Slesinger estate argued that it still held the rights to Winnie-the-Pooh, kicking off a legal battle that would span two decades. The estate also argued that Disney falsely reported their annual revenue, affecting the agreed upon 2% stake they were entitled to, and claimed $2 billion in damages.

The original 1961 deal held that the Slesinger estate would sell the entirety of the licensing rights to Disney, while retaining a 2% share of the franchise’s annual revenue. A court case, brought up in 1983, allowed the former owners to take a brief repossession of the rights, to then redistribute them back to Disney. This odd legal maneuver set the stage for a 1991 litigation case in which the Slesinger estate argued that it still held the rights to Winnie-the-Pooh, kicking off a legal battle that would span two decades. The estate also argued that Disney falsely reported their annual revenue, affecting the agreed upon 2% stake they were entitled to, and claimed $2 billion in damages.

The case was messy and saw impropriety on both sides. Disney was accused of destroying some forty boxes of documents, while the Slesinger company was found to have hired a private detective to rummage through the garbage at Disney headquarters. The debacle was settled only recently, in 2009, during which a handful of reports suggested Disney was close to losing its licensing rights entirely. After 18 years of litigation, things remained more or less unchanged, with Disney retaining the rights, and the estate entitled to its small royalty. The two companies are on seemingly amicable terms, for now.

When looking at the history of Pooh’s licensing, one can’t help but feel bad for Milne himself, who received so little from the franchise that would have never existed without his books. Although, we may be less surprised by the way in which people have fought ardently over profitable and contested property. Winnie-the-Pooh may be the first example of modern media licensing, but its example shows us how the industry might still be in its infancy.