There are some books where the story behind the story is just as interesting—if not more so—than the story itself. 007 creator and novelist Ian Fleming had largely avoided this scenario in the publication of his first seven Bond novels; however, Fleming’s eighth 007 novel, Thunderball, found Fleming and his protagonist in some of the most high-stakes peril yet—though Bond’s struggles against international crime syndicates pales slightly in comparison to Fleming’s entanglements with copyright lawyers.

Whatever the case, Thunderball marked several turning points for both Fleming and James Bond. While the novel was one of the most well-received and commercially successful Bond novels to date, the composition of the novel was fraught with roadblocks and speed bumps, which is perhaps part of what drove Fleming’s creative process and allowed him to unfold one of his more spine-tingling plots.

From the introduction of a new menacing crime organization and super villain to legal controversies to multiple film adaptations, Thunderball remains one of the Bond canon’s most interesting and intensely loved entries.

From the introduction of a new menacing crime organization and super villain to legal controversies to multiple film adaptations, Thunderball remains one of the Bond canon’s most interesting and intensely loved entries.

The Mission

Thunderball opens with M sending Bond on a two-week retreat to the Shrublands health clinic due to poor physical health caused by heavy drinking and smoking, not to mention wear and tear on Bond’s body and mental state from prior missions. While recuperating at the clinic, Bond meets Count Lippe, a member of the Red Lightning Tong criminal group from Macau. When Bond learns of the Tong connection, Lippe tries to kill him by tampering with a spinal traction machine; however, Bond is saved by a nurse and begins to investigate Lippe. He learns of SPECTRE, for whom Lippe worked.

SPECTRE, a global crime syndicate led by criminal mastermind Ernst Stavro Blofeld, has concocted a plot to hijack two nuclear warheads and use them to destroy two major global cities. In an effort to foil the plot, the Americans and the British launch Operation Thunderball to recover the atomic bombs and cripple SPECTRE’s ability to conduct global operations and espionage. M directs Bond to travel to the Bahamas to conduct operations and investigate SPECTRE’s movements. Once in the Bahamas, Bond meets CIA operative Felix Leiter and the two begin work observing SPECTRE.

It’s not long before 007 encounters Dominetta "Domino" Vitali, mistress of Emilio Largo, one of SPECTRE’s top agents and a major player in the hijacking of the nuclear warheads. After seducing her, Bond informs her that Largo killed her brother, a military pilot. Bond then recruits her to spy on Largo and the two quickly discover the atomic bombs are stored aboard Largo’s boat, the Disco Volante. Bond and Leiter alert the Thunderball war room of their suspicions of Largo and join the crew of the American nuclear submarine. An undersea battle ensues between the crews of each vessel as Bond engages in a fight with Largo, eventually killing him with a spear gun. Both bombs are recovered and Bond is sent to the hospital with Domino to recover.

FAQ

Thunderball was released March 27, 1961 in the United Kingdom after a fairly interesting and contentious process from composition to publication. Fleming initially conceived of Thunderball as a screenplay—the first instance of writing a Bond story directly for the screen. Fleming and several collaborators—primarily Irish director Kevin McClory and friends Ivar Bryce and Ernest Cuneo—conceptualized the story of Thunderball in late 1958 and early 1959. The original screenplay had several early working titles including SPECTRE, James Bond of the Secret Service, and Longitude 78 West.

As Fleming began work on the screenplay, his other collaborators set about to sell the film to various Hollywood studios and production companies but were unable to convince a studio to take the project on, largely due to financial and contractual difficulties. As the hopes for a film version of the story began to deteriorate, Fleming retreated to his Goldeneye estate in early 1960 and composed a novelization based on the screenplay conceived by McClory, Byrce, Cueno, and himself. Fleming submitted the novel for publication later that year and his three collaborators petitioned England’s highest courts in order to stop publication of the novel citing plagiarism on Fleming’s part. Several national courts heard the case and the issue was eventually settled with Fleming receiving sole rights to the novel while McClory was awarded film rights to the story.

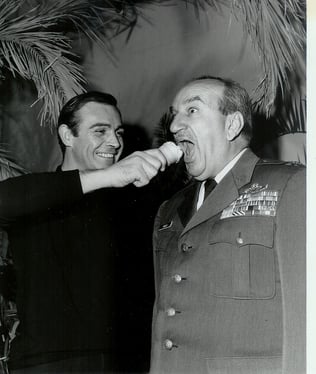

Publisher Jonathan Cape commissioned a first printing of more than 50,000 copies of Thunderball which quickly sold out and necessitated second and third printings. The novel was released in the United States by Viking Press and quickly became one of the top-selling 007 novels in the franchise’s short history. Since its publication, Thunderball has been adapted for film twice, first in 1965 with Sean Connery in the role and again in 1983 under the title Never Say Never Again, also with Connery in the lead. The 1983 adaptation was led by McClory, who made some significant changes from both the novel and the original film adaptation. Never Say Never Again is also the only Bond film to be produced outside the control of Eon Productions.

Publisher Jonathan Cape commissioned a first printing of more than 50,000 copies of Thunderball which quickly sold out and necessitated second and third printings. The novel was released in the United States by Viking Press and quickly became one of the top-selling 007 novels in the franchise’s short history. Since its publication, Thunderball has been adapted for film twice, first in 1965 with Sean Connery in the role and again in 1983 under the title Never Say Never Again, also with Connery in the lead. The 1983 adaptation was led by McClory, who made some significant changes from both the novel and the original film adaptation. Never Say Never Again is also the only Bond film to be produced outside the control of Eon Productions.

Field Notes

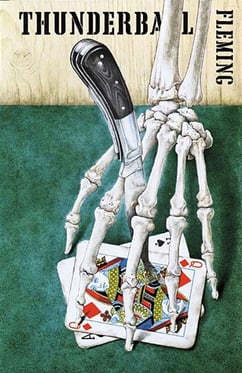

The first edition cover of Thunderball is arguably one of the most striking, intricate, and ornate covers to date in the 007 series. Conceived by artist Richard Chopping in conjunction with Fleming, the cover features a skeleton hand hovering over a set of playing cards with a knife cutting through the gaps between finger bones. The title is atop the cover—slightly obscured by the image of the skeleton—with Fleming’s name placed vertically in the top right corner.

In conceiving the cover art, Fleming desired something striking and elaborate. According to a series of correspondence between Chopping and Fleming, Fleming believed the cover was critical to the novel’s success, explaining that “The title of the book will be Thunderball. It is immensely long, immensely dull and only your jacket can save it!”

As with all previous first editions of Fleming’s Bond novels, the title page should consist of the publisher and the title—the back page should not contain anything but the publication year. In addition, no references to editorial or critical reviews should be present on either the front or back title pages.

The Bond Dossier will return with The Spy Who Loved Me...