The adventure begins in the ordinary world, where our hero gets the call to action; with the help of companions and mentors, he crosses the threshold into a supernatural world, where the old rules don’t apply. He faces a series of trials, culminating in an ultimate ordeal in which the hero is victorious. He earns a boon, which he carries back into the ordinary world.

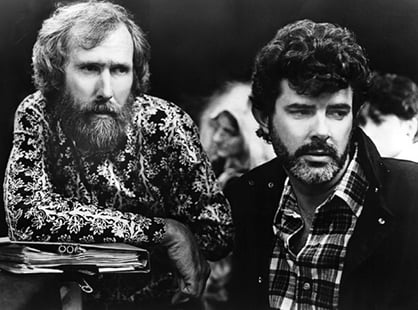

This is a succinct distillation of Joseph Campbell’s famed concept of the Hero’s Journey, yes, but it also describes George Lucas. Growing up in the ordinary world of Modesto, California, Lucas eventually received a call to adventure in the form of the Flash Gordon serials and Fellini movies that inspired him to become a filmmaker, where he was encouraged by his friend and mentor John Plummer to cross the sacred threshold into USC’s School of Cinematic Arts.

The trials, the ultimate ordeal, and the boon that Lucas earned all revolve around his most beloved creation: Star Wars (1977-2019). Though it was often a rocky journey to get A New Hope (1977) filmed and distributed, it changed moviemaking forever, setting a new standard and rewriting the rules for the blockbuster films (including Lucas’ own) that would follow it. And it earned Lucas more money and acclaim than one person could reasonably know what to do with.

The trials, the ultimate ordeal, and the boon that Lucas earned all revolve around his most beloved creation: Star Wars (1977-2019). Though it was often a rocky journey to get A New Hope (1977) filmed and distributed, it changed moviemaking forever, setting a new standard and rewriting the rules for the blockbuster films (including Lucas’ own) that would follow it. And it earned Lucas more money and acclaim than one person could reasonably know what to do with.

As with almost any hero’s journey, Lucas didn’t get there alone: He was helped by friends (notably by Steven Spielberg), and he was fueled artistically by the films of Akira Kurosawa, Sergio Leone, and John Ford.

But what about books? What books might have helped Lucas along his path to almost unimaginable artistic and professional success? We’re glad you asked.

Pulp Fiction

Of course, it’s been noted time and time again that Lucas’ most famous creation is, at base, a lovingly-crafted bricolage that borrows (some people might say steals) elements from older works pretty directly. Some of the most obviously borrowed elements come from the pulp sci-fi novels of the first half of the twentieth century. Sure, Lucas was influenced by televised serials like Flash Gordon—but he was also stealing hand-over-fist from writers like Doc Smith. Smith’s 1937 novel Galactic Patrol, which features a telepathic warrior destroying a planned military base using surreptitiously acquired plans, is a pretty obvious influence on the first film in the original Star Wars trilogy. Edgar Rice Burroughs, creator of Tarzan, also wrote a number of pulp science fiction novels that contributed to the grand vision of Lucas' films.

Isaac Asimov’s works were also an obvious inspiration for Lucas’ films. The concept of the lightsaber, for instance, is borrowed from the “force-blades” used in Asimov’s Lucky Starr (1952-1958) series. And it isn’t just a matter of individual technology—the galaxy in which the Star Wars films take place bears some similarity to that of Asimov’s Foundation novels (1942-1993)—which shouldn’t be surprising, considering how seminal Asimov’s work was in establishing the modern tropes and expectations for sci-fi galaxies. Lucas’ worlds all feel tremendously lived-in, as though they really were from ‘a long time ago,’ and one of the ways he achieves this effect is by way of small, world-building details that less revered sci-fi works tend to elide over. This includes the sheer number of different character designs used even in the background of, say, the Mos Isley Cantina, but it also comes in the form of the existing political tensions that are already present from the outset of the first movie.

Star Wars and Mythology

Though Lucas’ work is undoubtedly influenced by a ton of classic sci-fi and other pulp genres, “hard” sci-fi fans tend to bristle at Star Wars’ inclusion in the sci-fi genre. Why? Because it’s so obviously less interested in science per se than in crafting operatic stories with an epic, mythological sweep. As such, you’ll sometimes hear the series referred to as a “Space Opera”—though a “Space Epic” might be a more appropriate designation (considering that “Space Odyssey” is already taken).

This, again, is no confidence. It’s well established at this point that Lucas was hugely influenced by Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), a work of comparative mythology that compiles some of the recurring motifs and tropes that seem to crop independently of one another across world mythologies. Lucas relied heavily on this text to imbue his films with both the epic sweep—and as such it shares considerable DNA with the epic literature of the past few thousand years, including Homer’s Odyssey (c. 800 BC) and Iliad (c. 800 BC), Hindu mythology’s The Ramayana (c. 300), Hesiod’s poetry, and other ancient classics. If you look at his set and costume designs, one of the most striking things about them is the patina of history that clings to everyday objects—making speeders and blasters all feel like they have backstories of their own. By drawing from the wellspring of epics and folklore, he lends the same patina to his characters and plot arcs.

Second Order Inspiration

As if all of the books we’ve mentioned weren’t enough, there’s plenty of books that offered at least indirect inspiration to the acclaimed director. The list of influences that went into the creation of Star Wars is obviously quite long, and it’s mostly populated by other films—but many of those films are themselves adapted from or inspired by books. In The Phantom Menace (1999), for instance, the iconic pod-racing scenes are sometimes lifted shot-for-shot from Ben Hur (1959), which was itself adapted from Lew Wallace’s novel, Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1890). By the same token, the planet of Coruscant has some noted similarities with the world of Blade Runner (1982), which is based on Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968).

No doubt, we could keep finding literary connections ad nauseum. Suffice it to say that Lucas’ most beloved creation simply wouldn’t have existed without an immense literary history at its back. This isn’t a criticism—on the contrary. Some works of art wear there influences on their sleeves, while some appear to come, sui generis, out of the blue. Some rare works, like Star Wars, manage to do both at the same time.