Do you have a personal library, or do you have a collection? And is there really a difference between the two? It depends on who you ask. In general, we do think a book collection is distinct from a personal library, although the two are not necessarily separate from one another. Why does it matter? Well, the way in which you might conceive of and shape a personal library is likely to be quite different from the way in which you might conceive of and shape a book collection.

There’s no single definition of a library, we’d like to say up front. The notion of a library can mean different things to different people, and it may have various meanings in distinct cultural, temporal, and geographic contexts. According to the American Library Association, the word library has come to connote groups of both hard-copy and digital materials, including books, websites, microfilm and microfiche, and other materials. In The Librarian’s Book of Lists, George Eberhart defines a library as:

“a collection of resources in a variety of formats that is organized by information professionals or other experts who provide convenient physical, digital, bibliographic, or intellectual access and offer targeted services and programs with the mission of educating, informing, or entertaining a variety of audiences and the goal of stimulating individual learning and advancing society as a whole.”

This definition underscores the ways in which a library can be a resource for many people, while focusing less on the specific materials themselves as objects that shape the library. The Online Dictionary of Library and Information Science (ODLIS) offers a different definition, focusing instead on the physical objects that make up a library, citing the development of the word “library” from the Latin “liber,” which means “book.” Yet even the ODLIS definition focuses on the utility of the library, explaining that the term refers to “a collection or group of collections of books and/or other print or nonprint materials organized and maintained for use,” which includes “reading, consultation, study, [and] research.”

All that being said, when we tend to think of a personal library, do we really conceive of it as a collection of books that are for our use, or for the use of others? In some senses, we might. For example, many academics, journalists, booksellers, and people in other professions who rely on books and other media for reference might have a personal library that serves a utilitarian purpose. And while many people with personal libraries are not in the regular habit of lending out books to the public, they may lend their books out regularly to friends and family members. For example, more than 2.4 million users have downloaded the app LibraryThing to catalog their own books and to keep track of who has borrowed them.

How do we think of collections in ways that are distinct from libraries? You may have noticed that a number of the library definitions we cited above use the word “collection” within their definition, suggesting that sometimes libraries can be made up of collections. Yet do we all mean the same thing when we refer to a “collection”? Let’s take a look at that word and the different ways it might be used.

The Oxford English Dictionary provides eight different definitions of the word “collection,” but we think only one of those definitions is particularly relevant for considering the distinctions between a personal library and a book collection. It defines a collection as “a number of objects collected or gathered together, viewed as a whole; a group of things collected and arranged.” The first part of this definition doesn’t really get at the different between a library and a collection, since both are made up of books and other materials that are gathered together. In the second part of the definition, however, the OED starts to get at the ways in which a personal library might be distinct from a book collection. It refers to a group of objects that has been “collected and arranged.”

That second part starts to reveal where we think the difference lies. Now, you might be saying to yourself: a library is arranged! Indeed, libraries are arranged—some by the Library of Congress Classification system, some by the Dewey Decimal Classification system, and some by other systems that may be specific to the owner or to the institution. Sometimes libraries use organization and classification systems designed specifically to push back against the dominant models used by institutions in the western world. Yet libraries are not developed based on a particular theory of arrangement, whereas collections often are.

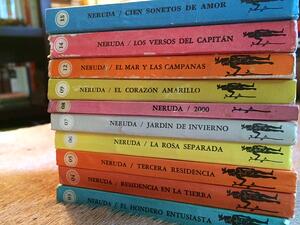

You might put together a collection based on the framing or arranging idea of a certain author, press, global region, specific social or political moment, etc. A personal library typically is much broader. While it may be arranged alphabetically, or it may be arranged based on one of the systems we just mentioned above, the underlying organizing principle doesn’t guide the act of adding to the library as it guides the act of adding to a collection. In sum, for us, the clear distinction between a library and a collection concerns the motivating theoretical framework. Collectors build their collections with an underlying idea in mind, while libraries are not created from a single motivating factor. Certainly, a library can include one or more collections, but it need not.

When Libraries Are Made Up of Collections

Sometimes personal libraries can be made up of more than one collection. For example, you may have a collection, or more than one book collection, that you consider to be part of your library. You may have other books in your library, as well, that are not necessarily included in a specific collection. We’ll leave you with the words of Walter Benjamin from his famous essay, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting.” For Benjamin, collections make up libraries, and libraries, too, are created by collectors:

“I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am. The books are not yet on the shelves, not yet touched by the mild boredom of order. I cannot march up and down their ranks to pass them in review before a friendly audience. You need not fear any of that. Instead, I must ask you to join me in the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open, the air saturated with the dust of wood, the floor covered with torn paper, to joint me among the piles of volumes that are seeing daylight again after two years of darkness, so that you may be ready to share with me a bit of the mood—it is certainly not an elegiac mood but, rather, one of anticipation—which these books arouse in a genuine collector.”