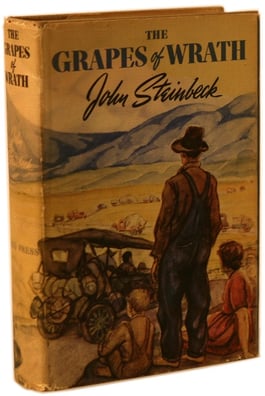

Since its publication in 1939, John Steinbeck’s magnum opus The Grapes of Wrath has been one of the most read, most studied, and most talked about works of American literature. The novel earned Steinbeck a National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize in addition to being cited by the committee that awarded him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962. Indeed, Steinbeck’s depiction of the Joad family’s journey across Dust Bowl era America has been adapted for both stage and screen, in addition to being marked indelibly into the American imagination, finding new relevance with each passing generation.

Because it is now so often studied in high school classes (where ‘the classics’ often seem to lose some of their edge), it can be easy to forget how controversial The Grapes of Wrath was upon its release. It was decried as propaganda by organizations on both the left and the right and was publicly burned by those who found alleged socialist leanings to be deeply offensive. When one reexamines the novel from this perspective, of course, it’s easy to see where the criticisms come from. With great perspicacity and acuity, the novel takes banks to task for the way they dehumanize employees and homeowners alike in the pursuit of profit (which pursuit often led to foreclosures and evictions). Steinbeck likewise turned his attention to land-owning California farmers, whom he deemed to have been unsympathetic, even inhumane, to the flood of migrants that sought a respite from the Depression in California. All of this, of course, occurs over a backdrop of skepticism toward the government and a deep concern with the depths of human greed and indifference.

Because it is now so often studied in high school classes (where ‘the classics’ often seem to lose some of their edge), it can be easy to forget how controversial The Grapes of Wrath was upon its release. It was decried as propaganda by organizations on both the left and the right and was publicly burned by those who found alleged socialist leanings to be deeply offensive. When one reexamines the novel from this perspective, of course, it’s easy to see where the criticisms come from. With great perspicacity and acuity, the novel takes banks to task for the way they dehumanize employees and homeowners alike in the pursuit of profit (which pursuit often led to foreclosures and evictions). Steinbeck likewise turned his attention to land-owning California farmers, whom he deemed to have been unsympathetic, even inhumane, to the flood of migrants that sought a respite from the Depression in California. All of this, of course, occurs over a backdrop of skepticism toward the government and a deep concern with the depths of human greed and indifference.

The slew of adaptations and homages (from John Ford’s 1940 film to Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways (2015), which many have read as a modern take on Steinbeck’s theme, and Bruce Springstein's 1995 album The Ghost of Tom Joad) signals that readers have always found something in Steinbeck’s work that speaks to their present moment. In that way, it may be naïve to think of the novel as being of never-before-seen relevance to contemporary America. And yet, the national conversation really does seem to need The Grapes of Wrath now more than ever.

The slew of adaptations and homages (from John Ford’s 1940 film to Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways (2015), which many have read as a modern take on Steinbeck’s theme, and Bruce Springstein's 1995 album The Ghost of Tom Joad) signals that readers have always found something in Steinbeck’s work that speaks to their present moment. In that way, it may be naïve to think of the novel as being of never-before-seen relevance to contemporary America. And yet, the national conversation really does seem to need The Grapes of Wrath now more than ever.

The first line of Malcolm Cowley’s 1939 review of the book for The New Republic begins, “While keeping our eyes on the cataclysms in Europe and Asia, we have lost sight of a tragedy nearer home.” Had the novel come out this year, the review could have begun the same way. Presidential candidates like Donald Trump and Ted Cruz are stoking the voting public’s fear of migrants (albeit those from other, war-torn or politically ravaged countries rather than Oklahoma). Meanwhile, the candidacy of someone like Bernie Sanders (who, just a few years ago, would have been considered a fringe candidate) signals the real possibility of socialist ideology making a resurgence in the country’s political discourse. Surely there is something to be gained, under such circumstances, by revisiting a work that so deftly reminds us of the ways that America responds to crises, and the avenues for not just greed and suffering but brotherly love and support that can unfurl in their wakes.