One of the less-remembered truths about the world of books is that, for much of their history, books were expensive. Even in the eighteenth century, owning more than a few books was a marker of middle class status. This fact, of course, did nothing to negate the desire that exists within almost everyone to be taken in by stories. As such, the nineteenth century saw a rise in deliberate attempts to produce inexpensive reading material, the most memorable of which efforts took the forms of the penny dreadful and the dime novel. Cheaply produced on low quality paper, these alternatives to more expensive reading material eventually became synonymous with sensational, low brow, and often lurid storytelling: all mantels that would come to be taken up by the pulps.

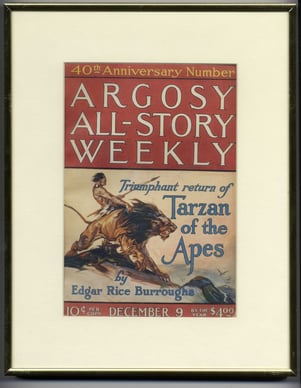

First arriving in the last decade of the nineteenth century, pulp magazines were printed on cheap paper made from wood pulp, and were priced significantly lower than the ‘glossy’ magazines against which they competed. Building on the traditions of the dime novel, pulps coupled their cheap paper with cheap printing techniques and cheap authors, which led to their existing in roughly the same cultural space that comic books would come to take up in the 1930s. These publications, Argosy being perhaps the most notable among them, would print tails of high-flown adventure from the likes of Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs, as well as early science fiction and horror writing, often with sensational illustrations plastered across their front covers.

First arriving in the last decade of the nineteenth century, pulp magazines were printed on cheap paper made from wood pulp, and were priced significantly lower than the ‘glossy’ magazines against which they competed. Building on the traditions of the dime novel, pulps coupled their cheap paper with cheap printing techniques and cheap authors, which led to their existing in roughly the same cultural space that comic books would come to take up in the 1930s. These publications, Argosy being perhaps the most notable among them, would print tails of high-flown adventure from the likes of Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs, as well as early science fiction and horror writing, often with sensational illustrations plastered across their front covers.

Though, again, decidedly low-brow, the pages of these magazines often contained the beginnings of the 20th century’s popular literary genres. To wit, both Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein (two of the more towering figures in 20th century science fiction) wrote for pulp magazines, not to mention Ray Bradbury and Philip K. Dick. On the western side of things, pulp magazines would often boast stories by Louis L’Amour and Zane Grey. Even more traditional literary styles were sometimes represented, with F. Scott Fitzgerald and Nobel Prize-winning author Sinclair Lewis occasionally viewing the pulps as, at the very least, good vessels for paying the bills.

While a post-war paper shortage and the growing ubiquity of the television forced pulp magazines into decline in the 1950s, their legacy persisted in the form of mass market paperbacks. These books would help keep pulp literature alive while simultaneously codifying the genres that pulp had become emblematic of, mostly mystery and science fiction (Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were right at home on newsstands). They often utilized the same style of eye-catching cover art and relied on the power of ubiquity (they could be found in grocery stores, diners, gas stations, etc.) to drive up sales.

While a post-war paper shortage and the growing ubiquity of the television forced pulp magazines into decline in the 1950s, their legacy persisted in the form of mass market paperbacks. These books would help keep pulp literature alive while simultaneously codifying the genres that pulp had become emblematic of, mostly mystery and science fiction (Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were right at home on newsstands). They often utilized the same style of eye-catching cover art and relied on the power of ubiquity (they could be found in grocery stores, diners, gas stations, etc.) to drive up sales.

Though the phenomenon of readily available, inexpensive fiction in supermarkets certainly hasn’t died, the tradition of over-the-top, often comically violent or noir-ish writing certainly doesn’t exist in the way it once did. And by many accounts, this is kind of a shame. Certainly from the perspective of Michael Chabon (whose 2001 Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000) deals with the early days of superhero comics), nostalgia for this era runs high. So much so, in fact, that he guest edited an issue of McSweeney’s Quarterly devoted to modern ‘pulp’ writing, drawing stories from Stephen King, Aimee Bender, and Dave Eggers.