“If you have a garden and a library,” said the Roman philosopher Cicero, “you have everything you need.” These are wise conditions under which to live a life: With books to connect you to humanity, and plants to connect you to nature. And as reading is a lifetime joy—one at which we get better with age—gardening is the same. To cultivate a garden for food or for beauty is a skill one can employ into the farthest reaches of old age. And, it is our luck that we may turn to our library, and peer through the pages of a gardening book, to bolster this passion.

Cicero, writing in the century before the birth of Christ, proves that literary minds have long taken a fancy to gardening. The out-of-doors has always been humanity’s strongest muse, and sensitivity to it is enhanced for those who work in nature, however modest their plot of land may be.

Cicero, writing in the century before the birth of Christ, proves that literary minds have long taken a fancy to gardening. The out-of-doors has always been humanity’s strongest muse, and sensitivity to it is enhanced for those who work in nature, however modest their plot of land may be.

Despite centuries of technical progress, Mother Nature’s machinations have stayed much the same. Rich soil makes for the brightest flowers, and grapevines still climb in a clockwise direction. For this reason, the entire tradition of gardening books remains somewhat relevant to the modern gardener of today.

There are many reasons to add to a collection of gardening books. Some readers may seek pragmatic assistance to improve their skills as gardeners, while others may want to appreciate artful illustrations, or delve into the richness of gardening history, or survey luxurious landscapes designed by the likes of Capability Brown.

In terms of artistry, it’s hard to beat the likes of Pierre-Joseph Redouté, called the “Raphael of flowers” and sometimes considered the best botanical illustrator of all time. Redouté spent half a century being an art tutor for French royalty, and produced 2,100 plates of illustrations of plants, frequently of species not registered before. It’s easy to see why his drawings were so popular in his time. They convey the special lifelike richness of flowers, despite being committed to the flat and eternal page.

Like that other legendary book illustrator of the natural world, Audubon, Redouté’s work makes up some of the highest-grossing products on the rare book market. In 1985, Empress Josephine’s copy of his book of 468 watercolors entitled The Lilies sold for $5.5 million. Contemporary fans of the painter can purchase affordable reprints of his work through art publishers like Taschen.

In terms of literary over visual arts, there is a tradition that extends close to the beginning of literature, with Hesiod’s Works and Days, in which the author doubles down the spiritual nobility of cultivating the land. Cicero was an avid gardener, too, professing that “tending vines is the rejuvenation and delight of my old age,” and he spoke at length about the joys of guiding the land’s earthly powers.

In terms of literary over visual arts, there is a tradition that extends close to the beginning of literature, with Hesiod’s Works and Days, in which the author doubles down the spiritual nobility of cultivating the land. Cicero was an avid gardener, too, professing that “tending vines is the rejuvenation and delight of my old age,” and he spoke at length about the joys of guiding the land’s earthly powers.

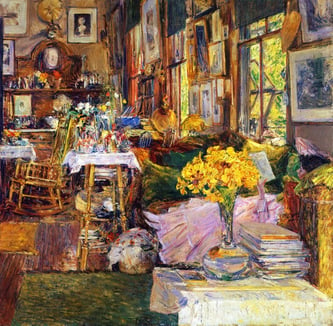

A little closer to our own time, we have the poet and writer Celia Thaxter, who lived to the final decade of the 19th century. Thaxter lived on the Isles of Shoals on the Atlantic Coast by Maine and New Hampshire. She cultivated a garden there, making a fertile nursery for flowers (which were used as decorations in her family’s hotel), and a beautiful, lush property. Many artistic visitors came by the verdant landscape, including Emerson, Hawthorne, Whittier, and artist Childe Hassam, whose 1894 painting The Room of Flowers is included adjacent to this paragraph.

Thaxter pronounced her love-affair with growing flowers in her book An Island Garden. Her work is a must-read for anyone who takes the spirit and philosophy of gardening as a sublime joy of life. “Like the musician, the painter, the poet, and the rest,” she wrote, “the true lover of flowers is born, not made. And he is born to happiness in this vale of tears, to a certain amount of the purest joy that earth can give her children, joy that is tranquil, innocent, uplifting, unfailing.”