Paper. We grab a scrap to jot down a phone number, we see movie posters, exchange greeting cards, hold paper books in our hands. We come in contact with so much paper, it’s hard to keep track, and this is during a so-called “digital age” when we should be immersed in a nearly paperless world. And yet, it continues to be necessary, wanted, and part of the fabric of our routines and desires.

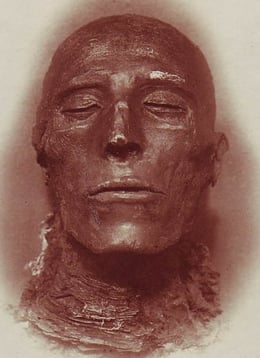

Imagine now, a world in which we need paper even more, for nearly everything. From communication to profit, paper is necessary. It’s basically the internet of the day, and the civilized world finds itself in desperate need and facing a real shortage. Enter: Mummy Paper!

Mummy Paper is the stuff of legends, much like the mummies it was supposedly torn from. American paper, made from cotton and linen rag fiber, became in short supply due to the huge newspaper boom. The rags, imported from Europe for the most part, were not sufficient to feed the newspaper industry properly.

Mummy Paper is the stuff of legends, much like the mummies it was supposedly torn from. American paper, made from cotton and linen rag fiber, became in short supply due to the huge newspaper boom. The rags, imported from Europe for the most part, were not sufficient to feed the newspaper industry properly.

The man on a mission to save the newspaper industry and locate a new source for linen rags was Dr. Isaiah Deck, who was a geologist, archeologist, and explorer. Visiting Egypt on another task, he discovered “Mummy pits” which were large burial sites full of mummies and parts of mummies, all wrapped in linen. He crunched some numbers and reasoned that there must be at least five hundred million mummies in and around Egypt, and the amount of linen they might provide would be substantial.

This is where fact and fiction part ways, and no one can truly tell what did or did not happen with any amount of certainty.

There are some specific primary sources that give the idea of importing and using mummy rags to make paper some credibility. Daniel Stanwood, son of I. Augustus Stanwood, communicates that his father told stories of importing mummies from Egypt and using the wrappings to make paper in his mills. There is also a letter from a Mrs. John Ramsey who had a father, who had a friend, who remembered unrolling the mummies, and that the “cocoon” used to resemble the human form, even after it had been stripped away, because it had been in that shape for so long.

Of course, these are very vague and anecdotal accounts and cannot be said to be true, rumor, or simply fabrication. However, it can be categorically confirmed that Egypt was an exporter of rags, regardless of where they came from. Newspaper accounts and archival records show that Egyptian rags arrived in the U.S. and were sold for about four cents a pound. There are also published articles regarding the specifics of the mummy paper trade, how much it costs vs. yield, oils and other chemicals that might interrupt the paper making process, and the color that the paper adopts as a result of origin.

There is a letter, published in the London Times in 1825 that gives a solid clue to the authenticity of the legend. Thomas Galloway as a British engineer and wrote the following to his father, who worked in manufacturing:

“…Wish to know if cotton as well as linen rags can be used for writing paper; 2dly if it is possible to make paper from straw, and what sort…; 3dly as a great quantity of linen rag is found upon all mummies and as it contains a great portion of the acid used for the preservation of the bodies, if it can be applied to the purpose of paper making.”

The significance of this letter for scholars is that it does not seem to be satirical (as many of the other written accounts have been dismissed as), nor does it seem to be a ghost story. Instead, it’s a fairly direct and practical question, and one buried in a series of other queries regarding the problem of producing paper. The lack of sentimentality, historical or archaeological value, or idea of destruction of graves is considerable and speaks to the general attitude towards mummies at the time.

Mummies were so plentiful and such curiosities that they were regularly unwrapped at parties and events for entertainment purposes, it is not beyond the possibility of consideration that the linen could easily have been made into newspaper. The mystery will remain, as any fiber testing would be vague at best, and would destroy the samples.

Whether speculation or truth, the idea of mummies finding their way into the hands of paper makers and rag merchants is fascinating. The two cultures—one that favored royalty and believed in reincarnation and everlasting life, and the other based mainly on profits and industry—having a connection that spans hundreds of thousands of years, and centering on sheets of paper, in turn creates an everlasting human connection.

STAUFFER, A. M. (2010). Legends of the Mummy Paper. Printing History, (8), 21-26.

Mummy Paper. (2015, November 1). Retrieved December 31, 2015, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mummy_paper

MOSHENSKA, G. (2014). Unrolling Egyptian mummies in nineteenth-century Britain. British Journal For The History Of Science, 47(3), 451-477.