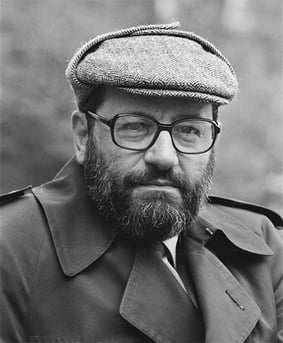

On February 19 of this year, world literature lost one of its most wise and respected members: Umberto Eco. A recent passing, one wonders if his reputation will go the way of many “greats” with penchants for humor and madness. Canonical reverence, as it does with Moby Dick, Ulysses, and others, often obscures the joyous play and zaniness of the object it praises. Eco, a literary trickster if there ever was one, would be disheartened to see his memory so distorted.

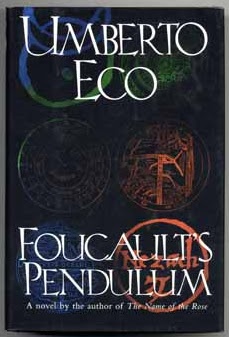

One of Umberto Eco’s most fun and famous novels is Foucault’s Pendulum, published in 1988. It concerns a group of vanity publishers (that is, people paid by authors to print books that no respectable house would publish voluntarily), who invent conspiracies, taken from the trove of wild manuscripts received through the years.

One of Umberto Eco’s most fun and famous novels is Foucault’s Pendulum, published in 1988. It concerns a group of vanity publishers (that is, people paid by authors to print books that no respectable house would publish voluntarily), who invent conspiracies, taken from the trove of wild manuscripts received through the years.

The ruse runs away from them, though, when these conspiracies turn out to be closer to the truth than they imagined. A detailed book that spins tales about the Knights Templar, the occult, celestial invention, world domination, and more, it has been called by one reviewer a “thinking man’s Da Vinci Code”; another said it was, “in effect, a long, erudite joke.”

Eco’s trickery has not been fun and games to all, however. The official Vatican newspaper was not amused by the author’s fanciful invention, calling him “a fabulatory pest who deforms, desecrates, and offends.” Some have alleged anti-semitism (author Anthony Burgess calls these accusations “irresponsible”), which likely derive from Eco’s reimaginations of Jewish history and tragedy. The Holocaust, so goes a theory in the book, was too methodical, too systematic to have been simply about extermination. Hitler was looking for something: a clue to a point in the hollow center of the earth, which if found, would make him Master of the World.

It would not be inaccurate to say that for Eco there is hardly a subject too sacred for tampering, too serious for inversion. His novel is comfortable with the grandest absurdities. What Foucault’s Pendulum describes—and what all the world’s secret societies have long sought—is the very telluric powers of the earth. This would allow those in control to wield the movements of the planet to their bidding; to raise mountains, provoke droughts, spin hurricanes, aggravate fault lines. If you possessed these powers, the nations of the world would bend to your will, lest you release a terrifying tempest or cataclysm upon them. Not yet absurd enough for you? A character suggests an engine of Hitler’s unlawful knowledge: the Nazi leader was, “perhaps, instructed by some Druid in his hometown.”

There’s also the confusing matter of the title. The book’s namesake comes from a pendulum housed in an arts and industry museum in Paris. The pendulum was invented by a nineteenth century scientist named Jean Bernard Léon Foucault, who created it to observe the rotation of the earth. It is not, as is often believed, named after friend to Eco and philosopher Michel Foucault. But even this is a matter of careful and playful obfuscation. Eco “specifically rejects any intentional reference to Michel Foucault,” he once said.

There’s also the confusing matter of the title. The book’s namesake comes from a pendulum housed in an arts and industry museum in Paris. The pendulum was invented by a nineteenth century scientist named Jean Bernard Léon Foucault, who created it to observe the rotation of the earth. It is not, as is often believed, named after friend to Eco and philosopher Michel Foucault. But even this is a matter of careful and playful obfuscation. Eco “specifically rejects any intentional reference to Michel Foucault,” he once said.

Admittedly, some readers are put off by the abundant rendering of intrigue and conspiracy of Foucault’s Pendulum. Its wild invention and revision makes the book a postmodern tome on par with the work of Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo. But to worry about missing a detail, to fuss over comprehending every turn and justification in a mad and mercurial fiction, might be to fall into the same trap readers often do when reading a big, playful work. In taking it all so seriously, it’s easy to miss the fun and silliness of the novel.

With this novel, Umberto Eco pulled off an unlikely feat: he wrote a book that was at once brainy and silly, popular and esoteric. Or, as Anthony Burgess, a big fan of Pendulum, wrote: “The book clearly needs an index.”