As of this writing, some 50 million copies of Johanna Spyri’s Heidi have been sold. A precursor to children’s book heroines from Pippi Longstocking to Eloise, Heidi has earned herself a place in countless childhood memories. Intelligent, caring, effervescent, often in the face of considerable challenges, it is not so hard to see why Heidi continues to be beloved by millions. Amid such artful successes, it can be easy to forget what its author Johanna Spyri contributed to the culture and posterity of her native Switzerland.

Johanna Spyri’s biography attests to the doctrine of it’s never too late. Beloved by millions today, Heidi was not the culmination of a long career but rather the start of a late-blooming one. It took her until her fifties to begin writing fiction in earnest, beginning with stories for adults that tackled mature themes like domestic abuse.

Johanna Spyri’s biography attests to the doctrine of it’s never too late. Beloved by millions today, Heidi was not the culmination of a long career but rather the start of a late-blooming one. It took her until her fifties to begin writing fiction in earnest, beginning with stories for adults that tackled mature themes like domestic abuse.

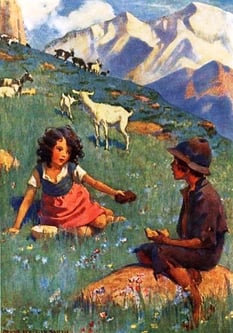

Soon after her first short stories came the four-week creative burst that produced Heidi, a tale whose eponymous young girl's search for happiness and faith has resonated in the hearts of countless readers. Orphaned at five, her aunt shuffles her to her paternal grandfather’s home in the alps. Cold-hearted at first, he begins to appreciate Heidi’s liveliness, and she befriends a nearby goatherd named Peter and his family, starting off a rich succession of Swiss setting and pastoral charm.

But her settling into the peace of a new home is interrupted when her aunt Dete retrieves her to be a playmate for a sickly rich girl in Frankfurt named Clara. Heidi works to adapt, but her ebullience is hindered by strict rules and her limited surroundings, and she enters periods of inanition and sleepwalking, an act which tempts the residents of the house to believe they are being haunted by a ghost for some time. Finally, she is brought back to the mountains, where she strengthens her faith, gets closer to her grandfather, and brings Clara, who herself is restored by the salubrious hearty diet and fresh mountain air.

It may not seem so at first, but the story is a very Swiss one. The country has always been a hodgepodge of cultures and languages, infiltrating in from the surrounding nations of Germany, Austria, Italy, and France. Its people speak from a palette of languages from these nations (Spyri wrote in German), and owes its identity to a particular mixture of all these lands. Swiss is famous for its neutrality, but few appreciate the compulsion to decline conflict when one shares a bond with her all her neighbors.

It may not seem so at first, but the story is a very Swiss one. The country has always been a hodgepodge of cultures and languages, infiltrating in from the surrounding nations of Germany, Austria, Italy, and France. Its people speak from a palette of languages from these nations (Spyri wrote in German), and owes its identity to a particular mixture of all these lands. Swiss is famous for its neutrality, but few appreciate the compulsion to decline conflict when one shares a bond with her all her neighbors.

In the narrative of Heidi, a Swiss girl finds herself adapting to a very Swiss, pastoral environment, only to be plucked away and thrust into the urban discontents of bordering Germany. Her return to the alps is a homecoming, and also a return to herself—no small feat in a country in which surrounding cultures are always pulling and vying for influence and supremacy. It is no accident that Switzerland’s role in literature is an intermediary one, whether to foreigners finding inspiration (Byron, the Shelleys, Nabokov) or to natives going off to greater cultural capitals (Rousseau). In Heidi, Johanna Spyri asserted that Switzerland was not merely a beautiful birthplace or stopover, but a home.