There are writers who write for the masses, those who write for fame, and those who write for the sake of art. There are others, like Camilo José Cela, who write with a voice to inform, excite, and evoke true response from others, all while still remaining true to himself. It is this virtue, this quest, that allowed the award-winning author to shape his nation’s literary heritage and earned him a spot in the canon of great writers.

Cela grew up in Iria Flavia, in Padrón, Spain. At 16, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and decided to create an advantage for himself by working from the sanitarium. The result was a book titled, Pabellón de reposo. He was hospitalized again a few years later, but this time for injuries sustained in fighting in the Spanish Civil War against the rebels. What would soon be seen as ironic, his work after being wounded was to be an official censor.

His first published novel was La familia de Pascual Duarte, written when he was 23. Unable to get the novel officially published in Spain, he took matters into his own hands and printed it himself in a garage in Burgos three years after writing it.

The novel focuses on a character who exists and functions outside of recognized morality, and the book was eventually recognized as helping to shape the post-WWII Spanish novel. It became incredibly popular in spite of the opposition by the dictatorship, and caused great friction. The violent nature of the story of a man committing murder was too much for the new dictatorship under General Franco. Undeterred and still true to his own vision, Cela continued to rock the boat.

With the Argentinian 1950 publication of La colmena (The Hive), a novel that depicted the true hardships of being an artist, he found himself censored: expelled from the Press Association in Spain and his name struck from the printed media. He embraced the controversy, enjoying the shock value of his erotic themes and the impact he was having on the Roman Catholic Church. Even in his later years he enjoyed making waves, going as far as creating a dictionary of dirty words entitled Diccionario secreto (Secret Dictionary, 1969–1971).

He excused himself from the country for a bit and took his family to the island of Majorca where he wrote a series of works: The Rose, Slide for the Hungry, Secret Dictionary, St. Camillus 1936, and Officiating Tenebrae 5. He never stopped being truly patriotic, however, and spent a year as a royal senator. Although now part of the higher ups, he still enjoyed making mischief, and wrote a book, naughtily entitled Chronicle of the Extraordinary Event of Archidona’s Dick.

Always naughty, always wanting to push the envelope, but also consistently exquisite and talented, Camilo not only won out the censors, and curried favor with readers, but took home many great literary awards: the Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras, the Premio Planeta, and the Premio Cervantes. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "for a rich and intensive prose, which with restrained compassion forms a challenging vision of man's vulnerability".

As a writer who served his country and his readers, his philosophy as an artist was that he must be true to, and serve first, himself. Despite the personal and professional risks, Cela sought to write to the end of satisfying his own conscience and being aware of his own ethics and morals. He rejected the idea of serving the critics and laughingly said that he had “been called a genius and...called mentally deficient. At least one of the two charges must be erroneous!”

As a writer who served his country and his readers, his philosophy as an artist was that he must be true to, and serve first, himself. Despite the personal and professional risks, Cela sought to write to the end of satisfying his own conscience and being aware of his own ethics and morals. He rejected the idea of serving the critics and laughingly said that he had “been called a genius and...called mentally deficient. At least one of the two charges must be erroneous!”

Not all of his efforts were simply “nose-thumbing”; he published a popular anti-fascist magazine that took issue with the Franco dictatorship and regularly invited controversy. When asked what he wanted on his tombstone he said "Here lies someone who tried to screw his fellow man as little as possible."

The time to pick out a headstone came in 2002 when heart disease claimed Cela at 85. Over the course of his life he wrote ten novels, and countless other works in the form of essays and poems, and he even had a side career as a painter and film actor. Never content to disrupt just one corner of the world, Cela was active, enjoyed a good fight, and stayed true to his cause: staying true to himself.

-Camilo José Cela. (2016, February 23). Retrieved March 31, 2016, here.

-The Nobel Prize in Literature 1989. (n.d.). Retrieved March 31, 2016, here.

-Cela: Spain's unflinching chronicler. (2002, January 17). Retrieved March 31, 2016, here.

-Miles, V. (2016). Camilo José Cela, The Art of Fiction No. 145. Retrieved March 31, 2016, here.

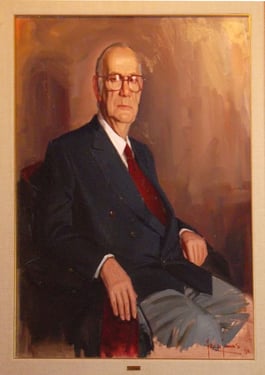

-Torija-Museo del Viaje a la Alcarria, retrato del escritor Don Camilo José Cela, pintado al óleo. (n.d.). Retrieved March 31, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 2012, October 7)

-Hojalata, H. D. (n.d.). Banco de Galicia, Vigo, Camilo José Cela viviu. Retrieved March 31, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 2012, April 5)