In the last 30 or 40 years, it’s become increasingly rare for a poet to achieve the same massive readerships as poets in the early part of the 20th Century. Yet the work of one 20th Century poet at the height of his popularity accounted for nearly 2/3 of all the book sales of living poets, according to the BBC.

That poet was Seamus Heaney (1939-2013), Irish national treasure and 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature winner whose work has influenced countless poets, writers, critics, and intellectuals worldwide. Born in Northern Ireland, writer Robert Lowell called Heaney “the most important Irish poet since Yeats.” During his long, illustrious career, he received nearly every prestigious literary award or honor in the English speaking world and taught at some of the world’s finest colleges and universities, including Harvard, Oxford, and a host of others.

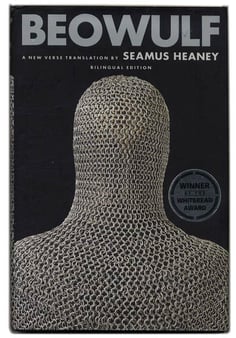

Heaney published in a number of genres including essays, criticism, and translation—his most famous work in translation being 1999’s Beowulf—but his poetry can perhaps be most easily categorized thematically in three movements or periods: growing up; the complexities of life and death; and maintaining his national Irish heritage in the face of immense popularity and appropriation, particularly by British culture.

Heaney published in a number of genres including essays, criticism, and translation—his most famous work in translation being 1999’s Beowulf—but his poetry can perhaps be most easily categorized thematically in three movements or periods: growing up; the complexities of life and death; and maintaining his national Irish heritage in the face of immense popularity and appropriation, particularly by British culture.

While poets, scholars, and critics know all too well the importance of Heaney's work, here are three Heaney poems—complete with excerpts—any literary-minded or conscious citizen should know that help illustrated these three distinct thematic movements in this famed poet’s canon of work.

Blueberry-Picking

I always felt like crying.

It wasn’t fair

that all lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they’d keep, new they would not.

Published in Heaney's 1966 debut collection, Death of a Naturalist, "Blueberry-Picking" is one of the more clear distillations of the collection’s thematic arc: youth, adolescence, early love, and the disappointment that can sometimes accompany maturity and coming-of-age.

The collection, which took Heaney several years to complete, contains 34 short poems—at least compared to some of Heaney’s later work—that are much like "Blueberry-Picking," which while wistful in their conception end on a note of melancholy or despair as the speaker reaches an ephianic moment about his youth.

Death of Naturalist contains several of Heaney's most well-known poems, including Digging, Death of a Naturalist, and Mid-Term Break.

"Mossbawn: Sunlight"

And here is love

like a tinsmith’s scoop

sunk past its gleam

in the meal-bin.

Appearing in Heaney's 1975 collection, North, the title of "Mossbawn" is taken from the family farm in Northern Ireland where Heaney was born. Whereas Death of a Naturalist focused heavily on youth and childhood and how our earliest moments can influence us throughout our lifetime, North is more concerned with the fragility of life and the inevitability of death and how humans copes with each condition.

Appearing in Heaney's 1975 collection, North, the title of "Mossbawn" is taken from the family farm in Northern Ireland where Heaney was born. Whereas Death of a Naturalist focused heavily on youth and childhood and how our earliest moments can influence us throughout our lifetime, North is more concerned with the fragility of life and the inevitability of death and how humans copes with each condition.

North also begins Heaney’s exploration of violence and suffering relative to the conflicts in Northern Ireland at the time many of these poems were written and published. Likewise, many of these poems also show the early beginnings of Heaney’s own internal negotiation about his heritage and cultural identity.

"Mossbawn," which ostensibly depicts Heaney’s aunt Mary baking and working in the kitchen and for whom the poem is dedicated, was composed and published in two parts ("Sunlight" and "The Seed Cutters") and is one of the collection’s anchors—a pillar of a poem that charts a thematic course for the rest of the poems within the collection to follow. Much like most of Heaney’s work, there is an underlying sadness and despair woven into the precise, poetic language and imagery that creates a sense of urgency and emotional heft common throughout Heaney’s writings.

"An Open Letter"

Be advised

My passport’s green

No glass of ours was ever raised

to toast the Queen

Though "An Open Letter" was never actually published in a proper collection, it’s an important marker in the evolution of Heaney’s career and thematic preoccupations. Written in response to one of his poems being included in a British anthology of poetry, the brief work is a shot-across-the-bows at the appropriation of his work by British culture, a development for which Heaney had very little patience.

Though "An Open Letter" was never actually published in a proper collection, it’s an important marker in the evolution of Heaney’s career and thematic preoccupations. Written in response to one of his poems being included in a British anthology of poetry, the brief work is a shot-across-the-bows at the appropriation of his work by British culture, a development for which Heaney had very little patience.

This third wave of Heaney’s career was also represented in essays, articles, plays, and other literary expressions throughout the late 1980s and mid 1990s, perhaps punctuated none more vehemently than Heaney rejecting an offer to be recognized as England’s poet laureate.

Heaney’s desire to retain his Irish identity was also evident in his personal life. He moved to Sandymount, Dublin in the late 1970s and remained there until his death in 2013.