“It seems pointless to be quoted if one isn’t going to be quotable…

it’s better to be quotable than honest.”

–Tom Stoppard, 1973

Many are, no doubt, familiar with Tom Stoppard’s work without being aware of it. The prolific Czech-born British playwright’s talents extend beyond the stage to the screen and the radio. Not only will many who would otherwise avoid absurdist drama have delighted in his 1988 Oscar-winning film Shakespeare in Love, still others will have seen 1989's Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade without knowing that Stoppard had a hand it.

Though he is uncredited, Steven Spielberg insists that Stoppard “was responsible for almost every line of dialogue in the film.” This means that we can thank the master playwright for such inimitable lines as the Knights Templar's “he chose… poorly,” and Sean Connery’s impassioned “goose-stepping morons like yourself should try reading books instead of burning them,” the latter of which echoes the author's often addressed concerns about censorship.

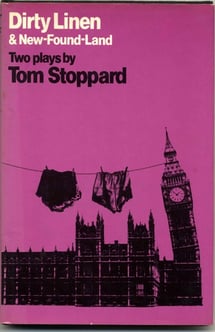

Where Stoppard shines most brightly, of course, is in his own work. And while fewer people have likely read Dirty Linen and New-Found-Land (1976) or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) than have seen the Indiana Jones movies, these plays are not exactly marginal.

Where Stoppard shines most brightly, of course, is in his own work. And while fewer people have likely read Dirty Linen and New-Found-Land (1976) or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) than have seen the Indiana Jones movies, these plays are not exactly marginal.

His 1972 breakout play Jumpers gained wide recognition not just for its exacting critique of modern philosophy and its expert farce, but for its eminent quotability. “It’s not the voting that’s democracy,” protagonist Dotty says, “it’s the counting.” Combined with a later quote by George (“How the hell do I know what I find incredible? Credibility is an expanding field...Sheer disbelief hardly registers on the face before the head is nodding with all the wisdom of instant hindsight.”), the viewers get an early indication of what Stoppard’s future work will concern itself with.

Having fled Czechoslovakia as a child to escape impending Nazi occupation, Stoppard shows an irrepressible concern with the political. Questions about democracy, of course, are always counterbalanced with musings about language and the absurd.

His 1974 play Travesties, for instance, exhibits similar concerns. “Causality is no longer fashionable owing to the war,” says Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara, whose time in Zurich with Lenin and James Joyce during World War I is the play’s central concern. Later in the play, Joyce himself gives an impassioned defense of the importance of the artist.

“An artist,” he says, “is the magician put among men to gratify — capriciously — their urge for immortality. The temples are built and brought down around him, continuously and contiguously, from Troy to the fields of Flanders. If there is any meaning in any of it, it is in what survives as art, yes even in the celebration of tyrants, yes even in the celebration of nonentities. What now of the Trojan War if it had been passed over by the artist's touch? Dust. A forgotten expedition prompted by Greek merchants looking for new markets. A minor redistribution of broken pots.”

This stands in opposition to another classic quote:

“To be an artist at all is like living in Switzerland during a world war. To be an artist in Zurich, in 1917, implies a degree of self-absorption that would have glazed over the eyes of Narcissus.“

As for which one Stoppard believes, we can only rely on another quote of his: “I write plays because dialogue is the most respectable way of contradicting myself.”

|

|

|

Photo Courtesy of wikimedia commons and used under CC license 3.0 |

One of Stoppard’s most well known works, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (adapted into a 1990 film of the same name), is an impossibility of clever phrasing and absurd musings. The play, which imagines two minor characters from Hamlet locked in a Beckett-esque existential afterlife, has just as much to say about theatre itself as it does the absurdity of existence. For instance, The Player, the leader of troupe of traveling actors, famously explains, “We do on stage things that are supposed to happen off. Which is a kind of integrity, if you look on every exit as being an entrance somewhere else.” Later on, the title characters have a quintessentially Stoppardian exchange:

By combining Oscar Wilde’s lightning-fast dialogue with Samuel Beckett’s existentialism (to say nothing of all that is obviously borrowed from Shakespeare), Stoppard creates one of the century’s most compelling theatrical hybrids.

It is, of course, not only Stoppard’s plays that contain pearls of equal wisdom and vexation. In interviews, Stoppard is just as quick-witted as any of his characters. In a profile for the New Yorker, Kenneth Tynan recounts Stoppard’s version of a pre-show address:

“I began my talk by saying that I had not written my plays for purposes of discussion. At once, I felt a ripple of panic run through the hall. I suddenly realised why. To everyone present, discussion was the whole point of drama. That was why the faculty had been endowed — that was why all those buildings had been put up! I had undermined the entire reason for their existence.“

In a different profile at The Telegraph, William Langley notes, “(w)hen Harold Pinter was lobbying to have London's Comedy Theatre renamed the Pinter Theatre, Stoppard wrote back: "Have you thought, instead, of changing your name to Harold Comedy?" Would we expect anything less from one of the last century’s most able playwrights?