Vincent Van Gogh lived a short life and committed suicide when he was only 37 years old. For many painters, writers, and collectors, Van Gogh’s story is an interesting one, often shrouded in mystique due to the artist’s own struggles with mental health issues and psychic instability. After his death, when Van Gogh’s paintings finally received the acclaim that they never did in his lifetime, public interest also grew surrounding the artist’s life story. Rumors circulated about his madness and his creative genius. In the 1920s, a young Irving Stone (born Irving Tennenbaum) traveled with his then-wife Lona Mosk to Paris, where he began investigating Van Gogh’s life and works. Stone’s research led to the critically acclaimed biography Lust for Life (1934).

Origins of the Biography: Dr. Félix Rey’s Letter About the Ear

Paris is a location that was central to Van Gogh’s life and work, and it is also a storied city for so many artists and writers. In the 1920s, when Stone spent time in Paris, he’d have been in the same city as Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and other expatriates. Yet Stone’s experiences in France were certainly different from those of the famous novelists and poets living in the capital. Stone had just graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, where he had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English. For several months, Stone’s research into Van Gogh’s life in Paris included attempts to contact the artist’s doctor, Dr. Félix Rey. Soon Stone would receive a document that would change the course of his own life and work, and would propel Lust for Life into the public spotlight.

Stone received a letter from Dr. Félix Rey, which confirmed that Van Gogh had sliced off nearly his entire ear, and not just a portion of his ear. Stone received a handwritten letter from Rey on the doctor’s personal stationery, dated August 18, 1930. Rather than beginning the letter with the customary greeting, Rey drew an image of an ear, with a dotted line along the length of the entire ear. In French, next to the sketch, he wrote, “the ear was sliced with a razor following the dotted line.” Underneath, he drew another image, showing the side of a face and a small nodule. Here, he wrote, “the ear showing what remained of the lobe.” Finally, underneath the two sketches, Rey wrote to Stone:

I’m happy to be able to give you the information you have requested concerning my unfortunate friend Van Gogh. I sincerely hope that you won’t fail to glorify the genius of this remarkable painter, as he deserves.

Cordially yours,

Dr. Rey

Stone and his wife returned to the U.S. and settled in Greenwich Village in New York City, and the biography was published in 1934. The letter took on its own fascinating history, and eventually ended up in Special Collections at The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley—Stone’s alma mater, and the location of Stone’s papers.

Indeed, the note from Dr. Rey is now in a large collection that contains more than 550 boxes of Stone’s correspondence, drafts, personal writings, and other ephemera. In 2016, after conducting research in the Stone collection, art historian Bernadette Murphy published Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story, a follow up in many ways to Stone’s Lust for Life.

Lust for Life: A History of Its Own

In the years that followed the initial publication of Lust for Life, the biography became widely popular and propelled Stone to fame. Nearly three decades later, he published a biography on the artist Michelangelo, The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961). In 1984, a 50th anniversary edition of Lust for Life was published and readers were reintroduced to the biography, which is organized largely by the various cities and regions of Europe where Van Gogh lived and painted. The prologue begins in London with dialogue from Ursula Loyer, the woman from whom Van Gogh rented a room: “Monsieur Van Gogh! It’s time to wake up!” From London, the book follows Van Gogh to the Borinage in Belgium, various towns and cities in the Netherlands (Etten, The Hague, and Nuenen), Paris, and finally to the south of France (from Arles to Saint-Rémy to Auvers-sur-Oise).

Prior to the 50th anniversary edition of Lust for Life, the book was adapted into a film of the same name in 1956 starring Kirk Douglas (as Van Gogh) and Anthony Quinn (as Paul Gauguin), and directed by Vincente Minnelli. Like Van Gogh’s paintings, the movie was richly hued in Technicolor, and Quinn won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The film premiered in New York City at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

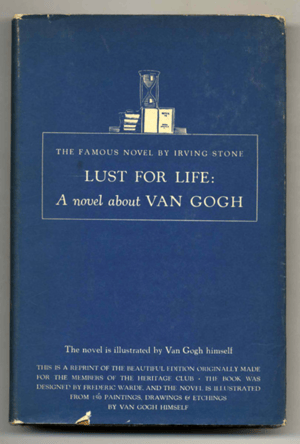

Over the years, the book was reprinted by various publishers, and some of those texts have become quite collectible. If you’re interested in the biography and are considering adding it to a collection of artist biographies, you might seek out the Franklin Library’s 1981 limited edited of Lust for Life, signed by the author and bound in leather with gilded pages. You might also try to locate a first edition with its original dust jacket, published by Longmans, Green and Company. And while you’re seeking out one of these editions, why not view the film?