Virginia Hamilton was a master storyteller who preserved black oral tradition through her intensive research uncovering riddles, stories, and traditions. Her career would span for more than 40 years, but her first book was published in 1967, a time when most books devoted to the African American experience dealt with issues of segregation and poverty. She termed her novels “liberation literature” and instead of problem storylines, her tales underscored the experiences of ordinary people. Among her works were picture books, folk tales, science-fiction stories, realistic novels, biographies, and mysteries.

Her books evidence a deep concern with tradition, memory, and generational legacy. In particular, how these concerns helped define the lives of American blacks from slavery onward.

Her books evidence a deep concern with tradition, memory, and generational legacy. In particular, how these concerns helped define the lives of American blacks from slavery onward.

Her first book for children was published in 1967, Zeely. Here she abandoned talking about gritty urban drama for a pastoral tale of enchantment. The characters happened to be black. It's not that race was absent in this book, it's that it was completely and unremarkably present.

The story is about a summer that a girl, Elizabeth, spends with her brother, John, at their Uncle Ross's farm. Her unexpected relationship with Zeely, the daughter of a tenant farmer, presents Elizabeth the opportunity to find out what her father meant when he told her the summer was going to be very important. Elizabeth starts making up stories on the train to the farm that increase in number when she sees a picture of a Watutsi queen in a magazine. She equates Zeely with the woman in the picture and she begins to imagine that she and Zeely are sisters. Elizabeth's feelings of importance build as she retells these stories to her friends, who take them as the truth. Only after Zeely meets with Elizabeth and talks about herself through real stories does Elizabeth learn the significance of knowing herself and of living for herself and not for the stories she makes up about others.

Hamilton's Family: A Long Line of Storytellers

Virginia Hamilton came from a multigenerational, extended family of storytellers. Her grandfather, Levi Perry, was born a slave in Virginia and came to Ohio via the underground railroad. As Hamilton grew up on a family farm in rural Ohio, she heard stories from her grandfather about his flight to freedom. The combination of her rural upbringing, her family's heritage, and that oral tradition came to play a significant role in her novels.

The novel M.C. Higgins, the Great, was published in 1974. It is a coming of age novel covering three days in the life of a teenager. It's set in the Appalachian Mountains on a fictional mountain in Kentucky, near the Ohio River. The community is being encroached upon by a mining company. The book highlights the almost surreal customs of the hill people, including their traditions of song and superstition. At the core of the book is the reconciliation M.C. must make between tradition and change. The book won the Newbery Medal in 1975, given to the author of what the Association for Library Service to Children deem to be the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. This book was also awarded a National Book Award.

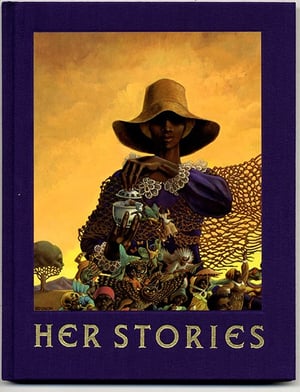

Virginia Hamilton also received the 1986 Coretta Scott King Award for The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales, the 1989 John Newbery Honor Book Award for Creation Stories from Around the World, and the 1996 Coretta Scott King Award for Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairy Tales and True Tales.

What she did not do was create saccharine, fluffy, or pristine literary worlds for children. She wove black folktales and narratives of African American life and experience into her work. She respected children's intelligence and their abilities to deal with ideas. She wrote 34 books in 29 years that included mysteries, biographies, folktale collections, a space-time trilogy, and a history of slavery in the United States.

She received the American Library Association's Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal in 1995 for her body of her work. She was also the first children's writer to be named a MacArthur Fellow. She continued to speak and collect awards until 2001. She died in 2002, and three books have been published posthumously.