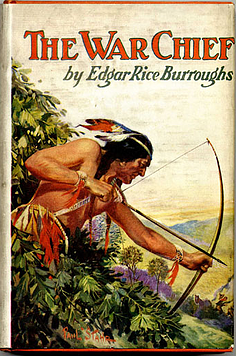

What are we to do with Edgar Rice Burroughs? A giant of science fiction and pulp writing in his time, modern readers find that not all of his work has aged well. Tarzan, adapted fifty times in Hollywood history, and most recently last year, seems more like a conspicuous colonial fantasy than an entertaining heroic tale. Can we dismiss it? The work Burroughs is most famous for, after all, was never meant for the college syllabus anyway, not in the way something comparable, like Heart of Darkness, was. Is it best to let this century-old book live in obscurity?

It is hard to say whether Edgar Rice Burroughs would much care about our modern queasiness or our debate over his merits. The author himself began writing not so much out of artistic frenzy but because he could: all the schlock he read in the pulp magazines was no less dreadful than what he could come up with. So Burroughs, working dead-end jobs in his mid-30s and in need of extra income to support a wife and two children, was compelled by a simple, admirable thought: “I could write something just as rotten.” And he could get paid for it.

It is hard to say whether Edgar Rice Burroughs would much care about our modern queasiness or our debate over his merits. The author himself began writing not so much out of artistic frenzy but because he could: all the schlock he read in the pulp magazines was no less dreadful than what he could come up with. So Burroughs, working dead-end jobs in his mid-30s and in need of extra income to support a wife and two children, was compelled by a simple, admirable thought: “I could write something just as rotten.” And he could get paid for it.

This is not an author who lived by the lofty doctrine of art described by Matthew Arnold, of the “the best that has been thought and said.” This is a writer who wrote 80 books, 26 of them about Tarzan, on a kind of dare to himself, that he could get away with it. He had fun doing so, both writing the work and spending the massive proceeds, merchandising his intellectual property and spending the revenue on his large California ranch, cars, and on keeping up with the Hollywood elite.

Burroughs got the last laugh, and his estate continues to enjoy the commercial merriment in the form of new commissioned books and adaptations. But in posterity, Burroughs has, in intellectual circles, become less popular, especially on account of his work’s ugly politics. Readers are told that Tarzan, the white protagonist in Africa (where Burroughs never visited), had the “confidence and resourcefulness which were the badges of his superior being."

"In his veins,” Burroughs writes, “flowed the blood of the best of a race of mighty fighters, and back of this was the training of his short lifetime among the fierce brutes of the jungle.” As Stuart Kelly in The Guardian notes, “The original book is not just casually racist, but deliberately ideologically and, to our modern eyes, offensively racist.”

This kind of condemnation is as easy as it is responsible and appropriate. Few fans of the Tarzan books are being made today, and certainly not at the rate that popular books from the same era, like The Great Gatsby, still enjoy. You can say all you want about Tarzan, and few in your audience will object or care. Perhaps in this way, they resemble their author, who also would have shrugged, then sipped a nice cocktail on his massive ranch, Tarzana, which took up enough space that it is now the name of a suburb.

With the release of the latest Tarzan film last summer, writer Dave Schilling argued that Tarzan was flawed beyond salvage or useful merit, predicated upon “the idea that a clever white man can bring order to the ‘dark continent’ through his own brand of clearly delineated, culturally specific morality.” This is an engaged perspective on a book that even by proper aesthetic judgments, by featuring stale characters and purple prose, is nothing majestic.

With the release of the latest Tarzan film last summer, writer Dave Schilling argued that Tarzan was flawed beyond salvage or useful merit, predicated upon “the idea that a clever white man can bring order to the ‘dark continent’ through his own brand of clearly delineated, culturally specific morality.” This is an engaged perspective on a book that even by proper aesthetic judgments, by featuring stale characters and purple prose, is nothing majestic.

To advise people not to read Tarzan may eventually sound like telling them not to read the Domesday Book: sound enough, but it assumes that people were planning to read it in the first place, or approach it as anything but a curiosity.

Perhaps Tarzan is most significant not in its pages, or even by its culturally pervasive adaptations, but in how we have not been able to escape the heroic mold it cast, which has given us everything from James Bond to the comic-book hero to the movie action star. As Ray Bradbury said with a deliberate sense of iconoclasm: “Burroughs is probably the most influential writer in the entire history of the world … By giving romance and adventure to a whole generation of boys, Burroughs caused them to go out and decide to become special." We can avoid the racism and the deficiencies of Tarzan by not reading the books. But the books’ merits and overarching influence are impossible to escape.