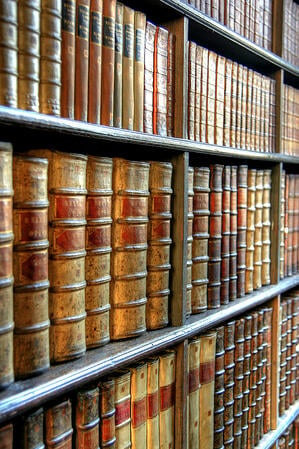

We often hear about people who are starting or adding to rare book collections, but it can be difficult to know exactly what counts as a “rare” book. Indeed, you may find yourself wondering: What is a rare book? The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines something that is “rare” in a variety of ways, and some of them certainly apply to rare books. For example, the OED defines a rare object as “a thing or things . . . occurring infrequently, encountered only occasionally or at intervals, uncommon,” or “of a kind seldom found, done or occurring; unusual, uncommon, exceptional.” These definitions can help us to understand why a book might be rare—it is found infrequently, is uncommon to see or to hold, and is exceptional in some capacity. Yet, as you might guess, not all rare books are exceptional in the same ways.

Sometimes a book is rare because of its age, while books can also be rare because of the materials with which they were produced or the condition in which they have been maintained. And yet, still, some books are extremely rare—and extremely valuable—even though they are not old and don’t have any particularly notable materials. Let us give you a very brief history of rare books as collectibles, followed by some important information about ascertaining the rarity of a book or ephemeral object.

A Brief History of Rare Books as Collectibles

Depending upon which century you traveled to, the definition of a rare book might vary in distinct ways. For example, in the 12th and 13th centuries (and for a few centuries that followed), only a few types of objects might be classified as rare books. Most immediately, the illuminated manuscript might come to mind. As the National Gallery of Art explains, illuminated manuscripts are “hand-written books with painted decoration that generally include precious metals such as gold or silver.” Most frequently, illuminated manuscripts were made of vellum—animal skin typically from a calf or sheep or goat. Illuminated manuscripts were made in monasteries between about 1100 and 1600, and they were particularly sought after by collectors in France and Italy in the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries.

With the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press in 1440, the production of illuminated manuscripts became much less frequent. And, accordingly, those illuminated manuscripts in existence became even rarer. Up until texts could become mass produced, there were only certain types of written texts that could fall into the categories of books, let alone rare books. By the 18th and 19th centuries, rare book collecting had become a common high-society pastime, and toward the latter end of that period the notion of “bibliomania” had become well known. In 1809, Thomas Frognall Dibdin wrote Bibliomania, or Book Madness: A Bibliographical Romance, in which he described some of the qualities that defined rare books as collectibles at that point in time: “First editions, true editions, black letter-printed books, large paper copies; uncut books with edges that are not sheared by binder’s tools; illustrated copies; unique copies with morocco binding or silk lining; and copies printed on vellum.”

What Makes a Particular Book Rare?

In the present day, what makes a particular book rare? Or, in other words, for people who consider themselves to be rare book collectors, how do they define the rarity of a particular text or object? The key is knowing that various qualities can make a book rare, and it is necessary to think about the specific context of a given collection when determining whether a book is rare. Some particular types of books, such as illuminated manuscripts, are inherently rare in the 21st century, yet there are numerous other things that can make a book rare. We want to discuss a variety of features that often arise in collecting rare books, and to dispel some myths about what makes a rare book especially rare.

Most rare books are “rare” because they are found or discovered infrequently, as the OED definition intimates. This means that the sheer number of a particular book in existence can make it rare, regardless of its age or condition. For example, every illuminated manuscript is distinct, making it rare (and also extremely collectible). Yet at the same time, books printed in small runs of only 50 or 100 copies by a fine press in the 21st century may also be incredibly rare. Some books are so rare that only a few were ever printed. For example, the “battlefield” edition of Pablo Neruda’ España en el Corazón: Himno a las Glorias del Pueblo en la Guerra [Spain in the Heart: Hymn to the Glories of the People at War] (1938) was printed on the battlefield of the Spanish Civil War with found materials on an abandoned press. Extremely few are in existence.

Next, you should avoid being convinced that an old book is necessarily a rare book. To be sure, although many old books are in fact rare, many are not. After mass printing became an option, various titles were printed in large quantities, and a lot of those books survive today. As such, an old family bible, for example—despite being old—may not be rare at all. Don’t be fooled into thinking all old books are rare books! At the same time, however, the fact that a book is old could, in some cases, make it rare. Think about the illuminated manuscripts we discussed above, for instance.

Onto condition: For a number of rare book collectors, the condition of the object matters when thinking about its rarity in relation to its market value. For example, if a first edition of a book was issued with a dust jacket, the condition of that dust jacket—and whether the book still has its original dust jacket—can be a difference of thousands of dollars depending upon the specific text. To be clear, some books are only rare when they are found in a particular condition. An early 20th-century novel might have been published and sold widely, yet few copies with an original dust jacket in fine condition may exist. Accordingly, those copies with intact dust jackets in fine condition may be rare objects while first editions of that same novel without a dust jacket might not be rare at all.

Finally, the particularities of the specific physical object can make it rare. For example, a paperback copy of novel might exist in every neighborhood bookshop, but that paperback can turn into an exceptionally rare book if it was owned and notated by a famous person. For example, a re-print paperback copy of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) might be widely available, but that book would become extremely rare if it contained margin notations from a writer like Nadine Gordimer.

Learn More About Rare Books and Begin Building Your Own Collection

You should keep in mind that there can be a difference between a rare book and a valuable or collectible book. Even if a book is rare, it may not be desirable by a collector and thus will not have the kind of market value of a text that is highly sought after. To learn more about rare book collecting, you might think about starting your own collection. Consider an author or topic that interests you, and get going! All it takes is one book to get you started.