If you’ve ever purchased a new book from a bookstore, a secondhand book, or a textbook for a course, you’ve most likely held a book that has an ISBN number. Sometimes college and university faculty will emphasize the need to buy a book for a course with a specific ISBN number to ensure that everyone has the same edition. You might even have entered an ISBN number if you’ve gone onto a publisher’s website with the intention of identifying or ordering a book. Anyone who has ever had to use an ISBN number already knows, most likely, that these numbers can have 10 digits or 13 digits. Even though many of us have identified a book by its ISBN number in some fashion, it’s rare to take a step back and to think about the purpose and history of the ISBN number. We want to tell you more about the history of the ISBN and why these numbers can be extremely helpful to book collectors.

What is an ISBN?

What is an ISBN? It is an International Standard Book Number (ISBN). As the American Library Association (ALA) explains, the ISBN is “a national and international standard identification number for uniquely identifying books.” In other words, ISBNs are used to identify books that are not part of serial publications. But don’t worry: serial publications also have a numbering system. The ALA clarifies that serial publications are identified through an International Standard Serial Number (ISSN), which is not to be confused with the ISBN. These numbers can be used to identify print and electronic materials. And, as a publication from the International ISBN Agency elucidates, ISBN numbers have even been used to identify microform materials and and CD-ROMs (for those of you who still remember some of those objects that were common not long ago but have now largely become obsolete). Even sheet music and other paper materials are assigned ISBNs.

ISBNs have five different elements. First, each ISBN has what is known as a “prefix” element. This prefix element is three digits, and it is always one of the following: 978 or 979. This prefix elements wasn’t added until 2007. We’ll say more about that shortly. Yet in the meantime, the second element of the ISBN is a “registration group” element. This second element can be anywhere from one to five digits in length, and it is used to identify several different features of the work, including the country or geographic region of production or, and the language in which the book was written. The third element is known as the “registrant” element, which can be as many as seven digits in length. This third element is used to identify the publisher or the publisher’s imprint. Then, the fourth element is the “publication” element, which can be as many as six digits in length. This element is used to identify the specific edition of the book. Finally, the ISBN ends with a “check digit” which is a single digit that, according to the International ISBN Agency, “mathematically validates the rest of the number.”

When ISBNs are being written out for human identification—in other words, for human readers to learn about the language and publisher of the book—hyphens are often added in between the elements.

How the ISBN Came to Be

The ISBN originated with W.H. Smith, one of the largest retailers of printed books in the United Kingdom. In the mid-1960s, W.H. Smith made plans to move to a computerized system and wanted a new way to classify books. The ISBN was conceived in 1966, and it was put into use just a year later. Other book retailers and interested parties also wanted to have a standardized system for classifying books, and eventually the ISBN went into wide use in the early 1970s.

Until 2007, ISBNs only contained 10 digits and did not include the “prefix” element we described. In 2007, the “prefix” element was added for additional classification of the book, and now the 13-digit ISBN is standard.

Why Should Book Collectors Know About ISBNs?

Okay, so here’s the gist of it: ISBNs are used to identify specific editions or printings of particular books and other objects. You can use the ISBN number to make sure you have the precise edition and printing of a rare book you are seeking out.

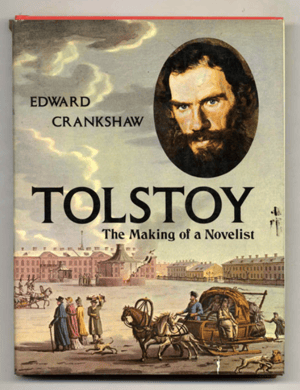

For example, let’s say you’ve decided to collect every copy of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina that you can find—from very early editions in Russian and French to paperback copies in a wide variety of languages. Now, a true first edition, so to speak, of Anna Karenina might refer to the serial installments of the novel that were published in Moscow in the magazine Russian Messenger between 1873-1877. Naturally, these magazines do not have ISBNs—they were printed long before the creation of the ISBN system. Likewise, English-language first editions from the late nineteenth century do not have ISBNs, just like any other editions published prior to 1966. For these early printings, collectors will use different identifiers.

After the ISBN came into wide usage, however, nearly all books listed for sale to the public received an ISBN. Accordingly, collectors of modern and contemporary editions and printings of Anna Karenina can rely on ISBN numbers to seek out translations of Anna Karenina in Russian, English, French, Arabic, German, Norwegian, Mandarin, Japanese, Spanish, Hindi, and many other languages. For example, a 2010 paperback edition of Anna Karenina in Hindi has the ISBN 978-8126719167. A 2013 paperback edition of Anna Karenina in Arabic has the ISBN 978-6589079989.

If your collection includes modern and contemporary books, you should absolutely know about ISBNs and how they can help in your book searches as you seek to develop your collection.