It’s perhaps one of the most famous moments of dialogue from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in which Romeo tries to convince Juliet how little it matters what her last name is or which house she comes from: “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Not to quibble with one of most revered technicians of the written word the world has ever seen, but I disagree. There’s something crucial to the sound or vibe of the right name for the right character.

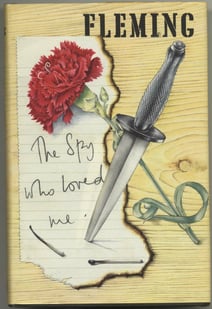

Whether the author works tirelessly to choose a character’s name, or whether a moniker hits in a lightning bolt of inspiration, there’s no debate that a name like Jay Gatsby is as breezy yet mysterious as the character himself; that Holden Caulfield is as big a mouthful as the angst-ridden teen’s headspace is cluttered; and James Bond is as confident yet unassuming as the way the character is portrayed to stride across a casino floor.

Whether the author works tirelessly to choose a character’s name, or whether a moniker hits in a lightning bolt of inspiration, there’s no debate that a name like Jay Gatsby is as breezy yet mysterious as the character himself; that Holden Caulfield is as big a mouthful as the angst-ridden teen’s headspace is cluttered; and James Bond is as confident yet unassuming as the way the character is portrayed to stride across a casino floor.

Abstract though it may be, the above examples illustrate how the right name can add depth and complexity to a character, while a clunky, ill-conceived name can not only detract from a novel or story but even break the suspension of disbelief in the reader, thus rendering the narrative suspect and faulty.

With that in mind, here are three unbelievable early or alternative names — and some brief explanations — for some of the most well-known characters in all of literature chosen by the authors who created them.

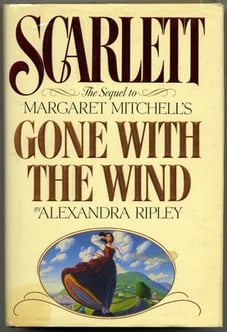

Pansy O’Hara

The world may know the heroine of Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 classic Gone with the Wind as Scarlett O’Hara; however, Mitchell’s original name for her leading lady was in fact Pansy.

The world may know the heroine of Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 classic Gone with the Wind as Scarlett O’Hara; however, Mitchell’s original name for her leading lady was in fact Pansy.

Mitchell’s novel was originally a broad, theatrical look at the pre-Civil War South roughly ten years in the making. At the same time, Mitchell worked as a journalist under the name Margaret Mitchell Upshaw, taking the last name of her then husband, Berrien “Red” Upshaw.

Gone with the Wind underwent several changes prior to publication from a reduction in scope to a change in the original title, Tomorrow is Another Day, taken from the novel’s final line.

It’s worth noting Pansy O’Hara may be the nearest miss in alternate character names, as Mitchell’s publisher requested she change O’Hara’s name to Scarlett just before the book went to press.

Sherrinford Holmes

While one Sherrinford Holmes is eluded to in several of the classic Holmes stories as an older brother of the infamous detective, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s seminal sleuth was first written as Sherrinford rather than the iconic Sherlock. While it’s unknown what prompted Doyle to make the switch, some believe the name was attributed to a highly-regarded cricket player of the day of which Doyle was a big fan.

While one Sherrinford Holmes is eluded to in several of the classic Holmes stories as an older brother of the infamous detective, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s seminal sleuth was first written as Sherrinford rather than the iconic Sherlock. While it’s unknown what prompted Doyle to make the switch, some believe the name was attributed to a highly-regarded cricket player of the day of which Doyle was a big fan.

But Sherlock Holmes wasn't the only character to receive a name overhaul before the stories were published. Doyle’s original name for Sherlock’s partner and documentarian, John H. Watson, was Ormond Sacker. It’s believed Doyle opted for the blander, less complicated name of Watson not long after settling on Sherlock rather than Sherrinford.

According to Doyle, the original names of the crime-fighting duo “gave no inkling of character,” hence the radical reworking of both.

Connie Gustafson

Sure, the jumps from Pansy to Scarlett and Sherrinford to Sherlock might not be that great, and in fact they pale in comparison to the leap between Connie Gustafson and Holly Golightly in Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Sure, the jumps from Pansy to Scarlett and Sherrinford to Sherlock might not be that great, and in fact they pale in comparison to the leap between Connie Gustafson and Holly Golightly in Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

What’s even more interesting is the center of Capote’s breakout 1958 novella was referred to as Connie Gustafson up until a final, hand-annotated manuscript was passed off to Capote’s editors prior to publication.

Whatever prompted the change must have been fairly seismic for Capote, who crossed out nearly 150 mentions of Gustafson in the final draft, replacing each mention with his protagonist’s new name.