“Hemingway Slaps Eastman in the Face,” read the New York Times headline on August 14, 1937. This famous spat happened one afternoon when Max Eastman—a prominent critic who wrote about politics, literature, and more—discovered that one of the subjects of his criticism, Ernest Hemingway, wanted to fight back. Hemingway, who was visiting New York at the time, walked into the Fifth Avenue location of publisher Charles Scribner & Son. There, in the office of editor Max Perkins, one of the most peculiar author exchanges of the century transpired.

Eastman had written some taunting lines about Hemingway in his essay, “Bull in the Afternoon.” The essay was a review of the author’s nonfiction account of Spanish bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon. “Some circumstance,” wrote Eastman, “seems to have laid upon Hemingway a continual sense of the obligation to put forth evidences of red-blooded masculinity." When Hemingway saw the book that contained that very disparaging essay on Max Perkins’ desk, he began to get "sore." That’s when he picked up the book, and searched for the libel that was written against him.

Eastman had written some taunting lines about Hemingway in his essay, “Bull in the Afternoon.” The essay was a review of the author’s nonfiction account of Spanish bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon. “Some circumstance,” wrote Eastman, “seems to have laid upon Hemingway a continual sense of the obligation to put forth evidences of red-blooded masculinity." When Hemingway saw the book that contained that very disparaging essay on Max Perkins’ desk, he began to get "sore." That’s when he picked up the book, and searched for the libel that was written against him.

Hemingway tried to get Eastman to read from his essay aloud. One line particularly irked Papa: “Come out from behind that false hair on your chest, Ernest. We all know you." Hemingway used this line to take the masculine competition that ensued in an absurd direction, perhaps even proving Eastman's point. Hemingway suggested that the authors compare chests. Eastman complied, giving Hemingway the opportunity to boast the authenticity of his vertiably hirsute torso, over the hairless chest of Eastman’s.

After this episode, Eastman still refused to read from his essay. That’s when Hemingway hit him in the face with the open book. The very book that was used in this attack, which remained in Max Perkins’ possession for some time, is decorated by this sensational inscription: This is the book I ruined on Max (the Prick) Eastman’s nose, I sincerely hope he burns forever in some hell of his own digging. —Ernest Hemingway. Indeed, the book’s spine is so damaged that it is perpetually inclined to open on pages 100 and 101, the position it was in during impact.

After this episode, Eastman still refused to read from his essay. That’s when Hemingway hit him in the face with the open book. The very book that was used in this attack, which remained in Max Perkins’ possession for some time, is decorated by this sensational inscription: This is the book I ruined on Max (the Prick) Eastman’s nose, I sincerely hope he burns forever in some hell of his own digging. —Ernest Hemingway. Indeed, the book’s spine is so damaged that it is perpetually inclined to open on pages 100 and 101, the position it was in during impact.

The slap is notable in part because it was the last event both authors could corroborate together. When a fight between two men ends, two separate stories are born, and the scuffle between these two writers was no different. Max Eastman claimed a valiant performance in the brawl. He said he threw Hemingway over a desk and stood him on his head. Hemingway, of course, rejected that Eastman had any such achievement of dominance.

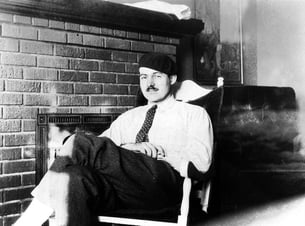

Hemingway, it cannot be denied, was a great self-publicist. He was startlingly eager to divulge information about the fight to reporters, apparently revealing himself to be just as preoccupied by chest-beating displays as Eastman claimed. Hemingway’s larger-than-life persona—that of brawling, of big game hunting, of guns, of war, of boxing—was always being shaped by the man himself.

|

|

Hemingway's mother Grace would often dress him up andrognously. |

When talking to the press, Hemingway emphasized his mercy and control. He didn’t want to upset his boss by brawling in his office. And if he had truly hit Eastman, he said, he would have flown through the window and plummeted onto the pavement of Fifth Avenue. When describing the fighting style of his opponent, he said, "He didn't throw anybody anywhere. He jumped at me like a woman—clawing, you know, with his open hands.” There was a minor scuffle after the book-slap, and Hemingway said he left unscathed. This was challenged by the fact that reporters noticed a swollen bump on the left side of his forehead. When asked if Eastman had inflicted that damage, Hemingway said no, and revealed two scars on other parts of his body, saying Eastman was not responsible for those, either.

Hemingway claimed slight remorse for having embarrassed the old man by socking him with the book. He said he felt a little bad for taking on a man ten years his senior. Despite this half-hearted apology, Hemingway didn't let the matter drop. He used the platform the press gave him to extend an offer to Eastman. If Eastman would be willing to exempt him from all financial claims for legal and medical recourse, Hemingway said he wanted to join Eastman in a locked room, where he'd have Eastman read what he wrote about him. The best man, Hemingway claimed, would unlock the door afterwards. If Eastman agreed, Hemingway would pay $1,000 to him or to a charity of his choice. Eastman, for some reason, never accepted the boastful writer’s offer.