In a Slate article in 2014*, Ruth Graham argued that adults who read young adult fiction should feel embarrassed. For her, YA meant simplistic story-telling, straightforward characters, and satisfying, unambiguous endings—all things that readers should, for her, outgrown before graduating to the moral, thematic, and structural ambiguity of adult literary fiction. Those who stick with YA ostensibly miss out on these things, as well as all the other benefits that adult literary fiction offers. These claims are not uncommon, and many readers who associate young adult fiction with the likes of Twilight (2005) are inclined toward a certain sort of knee-jerk agreement; but are they borne out by the history of YA literature?

One of the earliest works to be marketed specifically to young adults was S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders (1967). The popularity of Hinton’s work can be seen as a sort of inciting moment for the genre. It was an instance in which the foundations of modern YA literature as a discreet genre were laid by the publishing industry. Perhaps because it was written by a high-schooler, the novel took a dark, almost gritty view of adolescent life. Though its publication was certainly a watershed moment, 1967 was obviously not the first year in which a book focusing on adolescents was published.

One of the earliest works to be marketed specifically to young adults was S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders (1967). The popularity of Hinton’s work can be seen as a sort of inciting moment for the genre. It was an instance in which the foundations of modern YA literature as a discreet genre were laid by the publishing industry. Perhaps because it was written by a high-schooler, the novel took a dark, almost gritty view of adolescent life. Though its publication was certainly a watershed moment, 1967 was obviously not the first year in which a book focusing on adolescents was published.

As Borges said, “(t)he fact is that each writer creates his precursors.” In this way, the history of young adult fiction is a little like the history of the 100 Years War. The first 99 years certainly mattered, but it was not until the century mark that the name for the war that would persist through history became even theoretically available to those living through it. Thus, while it would have been nonsensical at the time to refer to (much less market) The Catcher in the Rye (1951) as YA literature, the trajectory of the genre allows us to regard Salinger’s iconic tale of adolescent grief as at least a work of proto-young adult lit, or even a seminal early example of the genre. The same logic could be applied to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954), J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937) (and, for some, even The Lord of the Rings (1954)) and John Knowles’ A Separate Peace (1959). The latter, in particular, delves deeply into the world of adolescent friendship in a way that is characteristic of the best entries into the genre, earning itself a place on the shortlist for the year’s National Book Award.

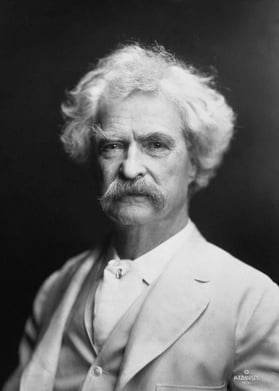

With the exception of The Hobbit and A Separate Peace, each of the novels listed in the last paragraph has something in common: in addition to appearing on TIME Magazine’s list of the 100 greatest young adult novels of all time, each one also appears on either TIME’s or Modern Library’s list of the best novels (read: adult novels) of the 20th century. Richard Hughes’ A High Wind in Jamaica (1929) also appears on both TIME lists (actually placing somewhat higher on the adult list than the YA list). Though absent, for obvious reasons, from 20th century-centric lists, Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) both warrant mentions on TIME’s YA list as well as almost any conceivable list of possible ‘Great-American-Novels’. These acknowledged literary gems are the first entries in a genre that writers like Ruth Graham decry as lacking in literary sophistication and gravitas.

One could argue that Twain’s novels precede the modern notion of young adulthood to which YA literature refers (the concept and the literature having evolved concomitantly in the twentieth century), but from a purely novelistic perspective, these early YA novels and YA precursors do, by all accounts, conform to Ruth Graham’s notions. They are easy enough to read and present conventionally satisfying endings. They are also, by and large, novels that no reader should miss. While it’s certainly true that readers who never deviate from YA literature will miss out on the glorious complexities of writers like Saul Bellow, Toni Morrison, and Vladimir Nabokov, there is no logical sense in believing that the reverse is not also true. After all, if novels of contorted psychological complexity and deep ambiguity are descendants of Fyodor Dostoevsky and his ilk, then many YA novels must be descendants of Mark Twain. Is there any reason why one should be better than the other? If unambiguous endings were good enough for Shakespeare, why shouldn’t they be good enough for serious modern readers?

One could argue that Twain’s novels precede the modern notion of young adulthood to which YA literature refers (the concept and the literature having evolved concomitantly in the twentieth century), but from a purely novelistic perspective, these early YA novels and YA precursors do, by all accounts, conform to Ruth Graham’s notions. They are easy enough to read and present conventionally satisfying endings. They are also, by and large, novels that no reader should miss. While it’s certainly true that readers who never deviate from YA literature will miss out on the glorious complexities of writers like Saul Bellow, Toni Morrison, and Vladimir Nabokov, there is no logical sense in believing that the reverse is not also true. After all, if novels of contorted psychological complexity and deep ambiguity are descendants of Fyodor Dostoevsky and his ilk, then many YA novels must be descendants of Mark Twain. Is there any reason why one should be better than the other? If unambiguous endings were good enough for Shakespeare, why shouldn’t they be good enough for serious modern readers?

In blocking an entire genre (with an unquestionable literary pedigree in its roots) from our view, we risk missing works like Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Story of a Part-Time Indian (2007). Alexie’s literary bona fides are, after all, unimpeachable—so to categorically refuse to read certain books of his based on market seems absurd. Perhaps Ruth Graham makes the mistake of judging an entire genre by its least inspired entries (as though mainstream literary publishing didn’t result in a slew of books each year just as unsatisfying or unfulfilling as those that Graham calls out), but it is a hard mistake to forgive. Graham’s article aims to rebuff those who would have everyone read whatever they like, but the real habit that leads to missing out on great books is not reading whatever one likes, but reading with a closed mind. Shouldn’t that, above all, be what embarrasses us?

*Source here.