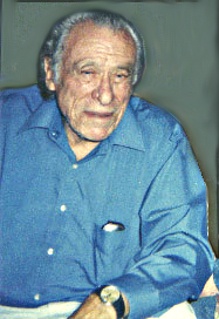

Sometimes, the persona of the writer outsizes the body of writing itself. Few examples of this are clearer than that set by poet and novelist Charles Bukowski. He committed to his pages the environment he knew best—that of lowlifes, the forgotten, and the destitute. This sort of life—with all its modest adventures to be found in saloons, motels, booze, and sex—has captivated the adolescent mind for years. And these readers are the chief reason Bukowski is kept alive at all.

Charles Bukowski was made possible, like many male writers of his time, by the counter-cultural movements of the sixties and seventies. He found the slog of life to be a pointless rat race, the religion of American pragmatism to be a sinkhole for the spirit, and preferred to pass his time on his own terms, which typically meant the indulgence of alcohol and women. It is not a demerit for a work of art to be depressive or to see the world as pointless and nauseating. Many great stories have done this. Yet Hamlet’s consciousness reaches the comsos; Bukowski’s merely propels him to the fridge for another drink.

Charles Bukowski was made possible, like many male writers of his time, by the counter-cultural movements of the sixties and seventies. He found the slog of life to be a pointless rat race, the religion of American pragmatism to be a sinkhole for the spirit, and preferred to pass his time on his own terms, which typically meant the indulgence of alcohol and women. It is not a demerit for a work of art to be depressive or to see the world as pointless and nauseating. Many great stories have done this. Yet Hamlet’s consciousness reaches the comsos; Bukowski’s merely propels him to the fridge for another drink.

Two Bukowski novels I read in my teen years, Factotum and Women, concern the protagonist Henry Chinaski’s revolving door of jobs and partners, respectively. Commitment of any kind is not the objective of Bukowski or his alter-ego Chinaski, which makes both books end up sounding like 270-pages lists of whiskey, women, and other diversions. At their best, his novels are diminished echoes of stronger works (although more on that at the end), and at their worst, his stories are puerile, solipsistic, and misogynistic.

His poetry is more diverse than his novels, and part of the appeal (and weakness) of his poems is simplicity. They often resemble paragraphs in which line breaks were inserted arbitrarily. They are easy to read, but unlike a great or even good poem, there is little to be gained from multiple readings. In the interest being fair, I will cite one of his strongest poems, “Alone with Everybody,” which I admit has merit:

The flesh covers the bone

and they put a mind

in there and

sometimes a soul

and the women break

vases against the walls

and the men drink too

much

and nobody finds the

one

but keep

looking

crawling in and out of beds.Flesh covers

the bone and the

flesh searches

for more than

flesh.There’s no chance

at all:

we are all trapped

by a singular

fate.Nobody ever finds

the one.The city dumps fill

the junkyards fill

the madhouses fill

the hospitals fill

the graveyards fillnothing else

fills.

This view of loneliness helpes us better understand Bukowski. His drinking and loafing and sleeping around is tied more to a fear of isolation than a haughty dissent from convention. But it is hard not to laugh at that penultimate stanza, which is a pessimistic list of refuse and death that could double for a lyric from a high school metal band. It is hard not to feel fatigued by how shallow Bukowski’s vision is. Successful metaphor is scant in his work, as is enriching irony. What you see is what you get, and what is seen is Bukowski is rarely impressive.

Then there is the issue of his misogyny. His book Women is predictably troublesome. He has peppered misogynist thoughts throughout his career, with quotes like “There are women who can make you feel more with their bodies and their souls, but these are the exact women who will turn the knife into you right in front of the crowd. Of course, I expect this, but the knife still cuts.” This is the very sort of portrait of women that we should pay attention to, for it is from a man who sees the gender as an adversary, as something to resent and be wary of. We see that not only were women to be collected in a life, they were to be kept in check. His personal life practiced what he preached. There is a naturally-disturbing video of him kicking a woman during an interview, an act that’s ugly but not unimaginable for a man of his temperament and crude philosophy.

Then there is the issue of his misogyny. His book Women is predictably troublesome. He has peppered misogynist thoughts throughout his career, with quotes like “There are women who can make you feel more with their bodies and their souls, but these are the exact women who will turn the knife into you right in front of the crowd. Of course, I expect this, but the knife still cuts.” This is the very sort of portrait of women that we should pay attention to, for it is from a man who sees the gender as an adversary, as something to resent and be wary of. We see that not only were women to be collected in a life, they were to be kept in check. His personal life practiced what he preached. There is a naturally-disturbing video of him kicking a woman during an interview, an act that’s ugly but not unimaginable for a man of his temperament and crude philosophy.

There is nothing wrong with enjoying something, but we should ask ourselves: What are we enjoying it for? Just because a writer is not Shakespeare does not mean we should not read her, but that is to say that we read her to get something different from what Shakespeare provides. I believe Bukowski readers to have a genuine interest in reading serious and literary works, that yes, present a dramatic vision of what it is to be a contemporary straight male. And in this respect, there are many stronger writers, of superior artistry, perspective, depth, and temperament that beat Bukowski at his own game. Here, I propose a list of alternatives that our reading time could be better dedicated to.

Henry Miller: Miller is at times a misogynist, but like a proper canonical male writer, his talent and intelligence makes it hard to dismiss him. There is a complexity and strangeness to Miller that Bukowksi (who was openly influenced by him) fails to reach. In Tropic of Cancer, a novel banned for thirty years for its explicitness, Miller makes an artistic case for openness to sensual experience as a way of life. Not just for Miller, but for all.

Raymond Carver: Carver’s short stories are a portrait of Americans in humble hardship. They drink, they divorce, they lose their jobs, and they pass time as best as they can. It is a sympathetic depiction of a people who we see all over in our country, who are usually passed over in favor of telling more dramatic narratives.

Ernest Hemingway: As a short story writer, it’s hard to find one better than Hemingway. As an illustrator of masculinity, Hemingway isn’t perfect, but his writing is far more interesting than Bukowski's navel-gazing.

Richard Yates and John Cheever: These men give us the professional, career-man’s version of modern emptiness. Their characters have affairs, drink, and deal with their loneliness in self-destructive and secretive ways. The prose is more artful, the characters richer, and deal more directly with the idea of how American prosperity did not American happiness make.

Malcolm Lowry: Miller is to women what Lowry is to booze, which is to say that both raise their subject to a kind of metaphor (the problem with Miller still remains that women are half of all people; and are therefore not a metaphor). Lowry, who brings to life his Mexican setting and alcoholic protagonist, uses alcoholism to talk about the hell of the self with the sort of depth Bukowski could only dream of.