Of course great authors are meant to be wise. We construct syllabi around their work, we give them Nobel Prizes, we call them geniuses and guardians of high culture. So how is that so many of them fall into politics that, when viewed from a slight distance of time or place, seem grotesque, and even immoral?

We may never find a persuasive answer to this question. But as generations become generally more concerned with tolerance and inclusion, the chauvinism of canonical authors has become a matter of increasing interest. Indeed, history provides examples of plenty of writers who embody jarring contradictions. At one turn, we find them writing with compassion and insight into the human spirit, while on the other, we see them advocate for disastrous and baffling politics.

We may never find a persuasive answer to this question. But as generations become generally more concerned with tolerance and inclusion, the chauvinism of canonical authors has become a matter of increasing interest. Indeed, history provides examples of plenty of writers who embody jarring contradictions. At one turn, we find them writing with compassion and insight into the human spirit, while on the other, we see them advocate for disastrous and baffling politics.

Here are some of literary history’s more notable cases of odd perspectives and allegiances.

Rudyard Kipling

Argued in a recent Washington Post op-ed to be “the most controversial author in English literature,” Rudyard Kipling has suffered a widespread dismissal based on his old-fashioned misogyny and racism. Yet it’s his imperialism that generates the most ire against the Nobel laureate. With infamous works like his poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” Kipling is hated by people who haven’t read him, and thanks to his reputation, they have no plans to do so. It's hard to pass judgment on either party, his fans or his detractors. How modern readers are supposed to set aside an author's harmful flaws to enjoy beautiful art is a major debate in the university classroom and beyond.

P.G. Wodehouse

Like Ezra Pound below, Wodehouse got in trouble for hosting a radio station for a country on the wrong side of World War II. But for all the international condemnation he received, Wodehouse’s entanglement was likely one of most innocent political scandals there could be.

At the outset of World War II, Wodehouse and his wife were living in France. As the Nazis advanced, they attempted to flee to America, but could not get out in time before the country fell to enemy hands. More or less trapped, he was coerced into doing five radio broadcasts for the Nazis. Allied populations in America and Britain initially thought the act treasonous, but further attention to the man and the situation proved there was no propaganda, or sign of allegiance to the Germans. Wodehouse, when living in the Hamptons years later, would startle his interviewer by not knowing how to drive to his house from New York City, nor did he know the common price of a book. He was a man perfectly insulated from the world beyond his writing, enabling the prosperity of his light spirit. “He is a man,” as Malcolm Muggeridge said of the scandal, “singularly ill-fitted to live in a time of ideological conflict, having no feelings of hatred about anyone, and no very strong views about anything.”

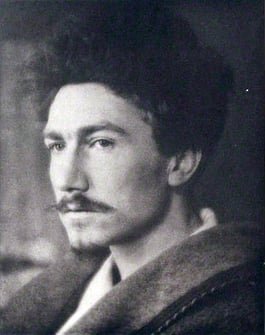

Ezra Pound

In the middle of World War II, in January, 1941, Ezra Pound began a radio broadcast for Mussolini’s Ministry for popular culture. Pound had long been notorious among intellectuals for his unfortunate politics, including an affection for fascism and privately pronounced anti-Semitism. (Accounting for T.S. Eliot, one realizes there is something strange about modernist poets and Jews.) In November 1941, poet William Carlos Williams wrote to Pound, saying “Can’t you see that every word you utter reveals to any intelligent and well-informed man that you know nothing at all?”

In the middle of World War II, in January, 1941, Ezra Pound began a radio broadcast for Mussolini’s Ministry for popular culture. Pound had long been notorious among intellectuals for his unfortunate politics, including an affection for fascism and privately pronounced anti-Semitism. (Accounting for T.S. Eliot, one realizes there is something strange about modernist poets and Jews.) In November 1941, poet William Carlos Williams wrote to Pound, saying “Can’t you see that every word you utter reveals to any intelligent and well-informed man that you know nothing at all?”

For his allegiance to Fascist Italy, Pound was charged with treason by the U.S. government in 1943. In 1945, he was evaluated and interred in a Washington, D.C. mental institution, where he was confined for over a decade. When let out in 1958, he returned to Italy, where he was better appreciated.

George Bernard Shaw

Shaw was but one of many idealists of his time who was stubborn to acknowledge Stalin’s atrocities. It is a generally embarrassing moment in Western intellectual history when too many thinkers were blinded by optimism to see that their hope had become a nightmare to his own people. George Bernard Shaw had a typically blemished record on picking the right leaders. He once referred to Hitler as a “very remarkable man, a very able man.” He expressed affection for Stalin and Mussolini, too.

It’s hard to say whether Shaw here made a series of errors; that the cruelty and fascism was hidden from him, or a shared tendency. He said once:

I don’t want to punish anybody, but there are an extraordinary number of people who I might want to kill…I think it would be a good thing to make everybody come before a properly appointed board, just put them there and say, ‘Sir or madam will you be kind enough to justify your existence. If you’re not producing as much as you consume or perhaps a little bit more then clearly we cannot use the big organization of our society for the purpose of keeping you alive. Because your life does not benefit us and it can’t be of very much use to yourself.

Shaw was a proud contrarian, and wore it as a badge of honor to be the only English writer with such opinions in his time. It is possible that such statements were made more out of a love of provocation than cruelty, but in the end there becomes little difference between what you say you believe and what you truly believe. If he was serious, what he says sounds like good politics, if mass murder and dystopia are your kind of thing.

Other authors who once supported Stalin, like Lillian Hellman, for instance, later changed their tune when the truth of Stalin’s atrocities come out. Indeed Shaw, as well as other writers, may not have been so amenable.