It’s not uncommon for writers to have day jobs entirely unrelated to writing. Wallace Stevens famously retained a job as an insurance executive throughout his illustrious career as a poet, reportedly dictating poems to his assistant during his lunch hour. William Carlos Williams, whose contributions to modernist verse can hardly be overstated, was a practicing doctor. Neither of these two, however, can touch the writer with perhaps the most impressive non-writing occupation: Anne Morrow Lindbergh, aviator.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh was primed for success from an early age. Raised as a Calvinist by a future U.S. Senator and the acting president of Smith College, Lindbergh learned to read and write at an early age, and began to keep a diary. She would continue this practice throughout her life, eventually publishing her diaries to considerable acclaim. In 1929, she married famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, who inspired her to earn her pilot’s license. She quickly became his co-pilot, undertaking over 40,000 miles of exploratory flying across five continents and surveying transatlantic air routes.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh was primed for success from an early age. Raised as a Calvinist by a future U.S. Senator and the acting president of Smith College, Lindbergh learned to read and write at an early age, and began to keep a diary. She would continue this practice throughout her life, eventually publishing her diaries to considerable acclaim. In 1929, she married famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, who inspired her to earn her pilot’s license. She quickly became his co-pilot, undertaking over 40,000 miles of exploratory flying across five continents and surveying transatlantic air routes.

Lindbergh’s achievements in aviation over the course of her life would earn her a place in the National Women's Hall of Fame and the National Aviation Hall of Fame, as well as a Hubbard Gold Medal from the National Geographic Society.

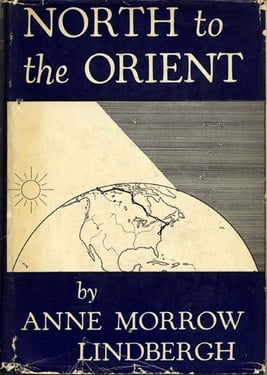

Beyond that, her flight hours would help jumpstart her budding literary career. Her first book, North to the Orient (1935), chronicled her journey with Charles to Japan and China, and their volunteer work during the Central China Floods in 1931. After its publication, North to the Orient would win the first ever National Book Award for Non-fiction. A National Book Award is obviously a huge accomplishment in and of itself, but how many people can claim a National Book Award and a spot in the National Aviation Hall of Fame?

Hardly one to be he mmed in by her daily life as a pilot, Lindbergh would go on to have a tremendously varied career as an author, publishing poetry and essays to complement her aeronautical non-fiction. Despite her overall success, Lindbergh was not immune to catastrophic errors in judgment. Her husband, in addition to being the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic, was also a vocal isolationist and eugenicist in the years leading up to World War II. Anne, apparently sharing many of Charles’ opinions, published The Wave of the Future in 1940 (hint: the wave of the future is fascism), in which she argued in favor of a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany. Following its publication, the Roosevelt administration would denounce it as "the bible of every American Nazi, Fascist, Bundist and Appeaser."

mmed in by her daily life as a pilot, Lindbergh would go on to have a tremendously varied career as an author, publishing poetry and essays to complement her aeronautical non-fiction. Despite her overall success, Lindbergh was not immune to catastrophic errors in judgment. Her husband, in addition to being the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic, was also a vocal isolationist and eugenicist in the years leading up to World War II. Anne, apparently sharing many of Charles’ opinions, published The Wave of the Future in 1940 (hint: the wave of the future is fascism), in which she argued in favor of a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany. Following its publication, the Roosevelt administration would denounce it as "the bible of every American Nazi, Fascist, Bundist and Appeaser."

After the war, Lindbergh would eventually rehabilitate her public image, aided in large part by the publication of Gift from the Sea in 1955 (though eventually giving an actual apology certainly helped). The book stands today as an early example of inspirational literature, taking the form of a series of meditations on youth, marriage, and life as a woman in the 20th century—all revolving around her time spent vacationing on Captiva Island in Florida. The book went on to sell three million copies, inspiring readers across the globe to this day.