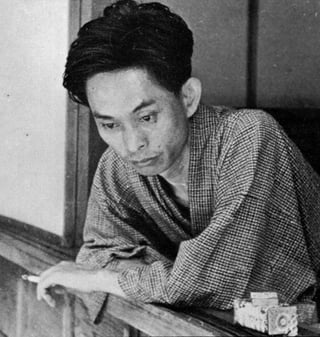

There are many authors who have won the Nobel Prize in Literature whose works enjoy continued success throughout the United States and in many parts of the world. Some Nobel laureates, however, have not remained as well-known as others. In the event that you have not been introduced to the lyrical, lonely writings of Yasunari Kawabata, we’d like to present you with some background information about this writer, who was also the first Japanese winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. In brief, he was born in Osaka, Japan in 1899 and committed suicide in 1972. Much of his most famous fiction is set just before and after World War II. In total, he wrote more than one dozen novels and short stories, although not all of them were finished. If you’re interested in reading more about this Japanese writer, where should you start?

Early Life and Works of Yasunari Kawabata

As the Nobel Prize website explains, the Japanese Nobel Laureate was born in Osaka just before the turn of the century, but his parents died shortly thereafter. As a result, his grandparents raised him in a rural setting until 1920, when Kawabata moved to Tokyo to study at the Tokyo Imperial University. While he was at the university, he helped to found the publication Bungei Jidai, which, as the Nobel Prize committee explained, became “the medium of a new movement in modern Japanese literature.” His first short story, “Izu Dancer,” appeared in 1927. Shortly thereafter, he began working on a novel for which he would become, perhaps, best-known in Japan: Snow Country (1937). Edward G. Seidensticker translated this book into English from the original Japanese in 1956. The novel depicts a love affair between the protagonist, Shimamura, and a geisha, Komako.

As the Nobel Prize website explains, the Japanese Nobel Laureate was born in Osaka just before the turn of the century, but his parents died shortly thereafter. As a result, his grandparents raised him in a rural setting until 1920, when Kawabata moved to Tokyo to study at the Tokyo Imperial University. While he was at the university, he helped to found the publication Bungei Jidai, which, as the Nobel Prize committee explained, became “the medium of a new movement in modern Japanese literature.” His first short story, “Izu Dancer,” appeared in 1927. Shortly thereafter, he began working on a novel for which he would become, perhaps, best-known in Japan: Snow Country (1937). Edward G. Seidensticker translated this book into English from the original Japanese in 1956. The novel depicts a love affair between the protagonist, Shimamura, and a geisha, Komako.

The text begins with “Part I,” introducing the reader to Shimamura, but also to the blanketed-white landscape of the remote Japanese town in which the novel takes place:

“The train came out of the long tunnel into the snow country. The earth lay white under the night sky. The train pulled up at a signal stop.

A girl who had been sitting on the other side of the car came over and opened the window in front of Shimamura. The snowy cold poured in. Leaning far out the window, the girl called to the station master as though he were a great distance away.

The station master walked slowly over the snow, a lantern in his hand. His face was buried to the nose in a muffle, and the flaps of his cap were turned down over his ears.

It’s that cold, is it, thought Shimamura. Low, barracklike buildings that might have been railway dormitories were scattered here and there up the frozen slope of the mountain. The white of the snow fell away into the darkness some distance before it reached them.”

Nobel Prize and Kawabata’s Suicide

After Snow Country was published in Japan, much of Kawabata’s work ceased until after World War II ended. In 1949, he published a set of narratives in serial form. By the 1950s, he had begun writing novels again, and he published three of them prior to winning the Nobel Prize in 1968.

After Snow Country was published in Japan, much of Kawabata’s work ceased until after World War II ended. In 1949, he published a set of narratives in serial form. By the 1950s, he had begun writing novels again, and he published three of them prior to winning the Nobel Prize in 1968.

When the Nobel Committee awarded Kawabata, it indicated that the Prize was “for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind.” In accepting the award, Kawabata recalled the poetic language of Dogen, a 13th-century priest, and Myoe, a 12th-century priest. The lines recalled some of Kawabata’s own language in Snow Country, reminding his listeners of both the beauty and terror of winter:

“In the spring, cherry blossoms, in the summer the cuckoo.

In autumn the moon, and in winter the snow, clear, cold.”

“The winter moon comes from the clouds to keep me company.

The wind is piercing, the snow is cold.”

Only four years after accepting the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first awarded Japanese writer committed suicide. While Kawabata is not read nearly as frequently as he should be, that doesn’t mean we can’t get his prose back into circulation. We recommend picking up a copy of Seidensticker’s translation of Snow Country and exploring the sparse yet beautiful language of this Japanese novelist.