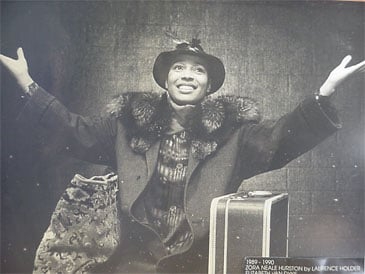

More than fifty years after her death, the world is finally catching up with Zora Neale Hurston. The independent and engaging African-American feminist was born on January 7, 1891 and grew up in the small African-American community of Eatonville, Florida. She was not exposed to the inequities of racism in the South as a child, or limited by the expectations of black literary movements in the 1920s as a young woman. Hurston wrote her novels, folklore, short stories, and essays not as a crusading pioneer, but as an anthropologist, an intellectual, and a lover.

Early Life and Influences

Zora Neale Hurston was born to a Baptist preacher named John and his schoolteacher wife, Lucy. She was the fifth of eight children who enjoyed a happy childhood just north of Orlando in the first all-black town in the United States. Eatonville was run by black men Zora could admire, and educated by black women she could emulate, and free of the guilt, angst, or confusion found in most communities during the early twentieth century in America.

Zora Neale Hurston was born to a Baptist preacher named John and his schoolteacher wife, Lucy. She was the fifth of eight children who enjoyed a happy childhood just north of Orlando in the first all-black town in the United States. Eatonville was run by black men Zora could admire, and educated by black women she could emulate, and free of the guilt, angst, or confusion found in most communities during the early twentieth century in America.

Hurston’s mother died when Hurston was thirteen, and her father remarried a woman who was only twenty years old. The couple was short on time and money to raise the family, opting to send Hurston to boarding school and eventually allowing her tuition to lapse. After being expelled, Hurston spent the next decade taking odd jobs as a maid or manicurist and earned a free high school education at Baltimore’s Morgan Academy by faking her age as 16 rather than 26. After completing her diploma in 1918, Hurston continued her studies at Howard University, where she earned her Associate’s Degree in 1920, and at Barnard College of Columbia University, where she earned her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Anthropology in 1927

During her time in Maryland, Washington, DC, and New York, Hurston was exposed to popular political and social ideas, including the Harlem Renaissance and the New Deal. Though she enjoyed the social company of artists and writers who debated these topics with her, Hurston rejected both ideas, asserting what many have since come to realize. She believed that Black life was more than a crusade, that Black speech patterns were not a hindrance to telling a story, and that the New Deal would develop a dependence of the Black community on the federal government. Her ideals were exceptionally unpopular at the time and led to the negative reception of her ensuing novels as unchallenging to the white establishment, though her critics all acknowledged she “knows how to write a story.”

Authorship and Love

During her 30's and 40's, Hurston traveled throughout the American South and to Jamaica, Haiti, and Central America on ethnic research financed by the Guggenheim Foundation and other wealthy philanthropists interested in Black culture. She wrote an anthropological study, Mules and Men (1934), and penned dozens of short stories based on African folklore and thriving Black culture such as Tell My Horse (1938) and Hoodoo in America (1931). During this time, Hurston also married twice to two very different men, one of whom was 25 years her junior, and enjoyed a love affair which was the basis of the romance between Janie and Tea Cake in Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). Her more personal novels tend to revolve around the concepts of love, happiness, and emotional strife. These include Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934) about a man with too many lovers, and Seraph on the Suwannee (1948), one of the few novels written by a Black author about white characters and struggles.

Despite the lack of critical acclaim during her life, Zora Neale Hurston has become the most famous female African-American writer of her time. Transcending movements and time periods in death as she did in life, hers is an enduring and permanent legacy to all sexes and cultures in the power of creative individualism and belief in oneself.