Take a guess: Who is the world's most translated author? One might assume that it's a literary titan, perhaps Shakespeare or Charles Dickens. But according to Index Translationium, UNESCO's database of book translations, the honor goes to none other than Agatha Christie, whose books have been translated into 103 languages.

Born on September 15, 1890, Christie went on to hold the world record as the best-selling novelist of all time; her novels have sold over 4 billion copies. Though Christie wrote six romances under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott, she's far more famous for her mystery novels. Her works comprise a considerable contribution to a genre with a long and fascinating history.

Born on September 15, 1890, Christie went on to hold the world record as the best-selling novelist of all time; her novels have sold over 4 billion copies. Though Christie wrote six romances under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott, she's far more famous for her mystery novels. Her works comprise a considerable contribution to a genre with a long and fascinating history.

Elizabethan Beginnings

Many crime fiction historians cite William Godwin's The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794) as the predecessor to the classical crime novel. Godwin's protagonist, Williams, suspects that his master, Falkland has murdered a neighbor and framed a tenant for the crime by planting evidence. Falkland learns of Williams' suspicion, fires him, and uses his wealth to persecute and harass him. Williams eventually publicly accuses Falkland, who confesses and dies. The novel certainly includes plenty of elements of classic crime and mystery fiction. Furthermore, Godwin worked like a detective himself to determine the book's plot; he started with his desired conclusion and worked backward to figure out a logical path to reach that end. Today's mystery writers still often use that technique to shape their stories.

But the antecedents of today's mystery genre are actually much older than Godwin's novel; its roots lie firmly in the true crime genre, which can be traced back almost all the way to the advent of movable type! By the sixteenth century, British readers already had a taste for true crime, which was satiated with broadsides, chapbooks, and pamphlets. It was common for printers to publish brief (often highly sensationalized) accounts of criminals' transgressions and confessions. These would frequently be distributed to spectators at the criminals' executions.

Meanwhile, the City of London and the County of Middlesex Sessions Papers were published eight times per year. These papers detailed all the latest trials. The Ordinary (or chaplain) of Newgate would also publish his own accounts of criminals' last hours, usually focusing on the state of their souls. In the popular press, The Mirror for Magistrates, which recounts the downfall of famous people in a series of poems, remained a bestseller throughout Queen Elizabeth's reign. During the following century, however, interest in true crime accounts waned only slightly. The upper class turned away from true crime literature, which was often gory and considered unsuitable for genteel readers.

Defoe's Novel Take on the Truth

Jack of all trades Daniel Defoe brought new life to the genre in the eighteenth century. First and foremost a professional journalist, Defoe had a knack for spotting commercially viable stories He recognized a new market for "truth--and decided to redefine what that meant. Defoe took a novel approach to criminal biography. Taking advantage of the public fascination with pirates, Defoe penned King of Pirates (1719) about real pirate Captain Avery. To lend his biography authority, and to give himself the competitive advantage over other Avery biographies on the market, Defoe composed two letters allegedly from Captain Avery himself, aiming to "set the record straight" regarding the inaccuracy of other published biographies.

Jack of all trades Daniel Defoe brought new life to the genre in the eighteenth century. First and foremost a professional journalist, Defoe had a knack for spotting commercially viable stories He recognized a new market for "truth--and decided to redefine what that meant. Defoe took a novel approach to criminal biography. Taking advantage of the public fascination with pirates, Defoe penned King of Pirates (1719) about real pirate Captain Avery. To lend his biography authority, and to give himself the competitive advantage over other Avery biographies on the market, Defoe composed two letters allegedly from Captain Avery himself, aiming to "set the record straight" regarding the inaccuracy of other published biographies.

A few years later, Defoe wrote A General History of Pirates (1724 and 1728). It includes biographies of about thirty real-life pirates, alongside at least one character that Defoe completely fabricated. He makes no distinction between the real and the invented.

Defoe used a similar technique with his biography of Jack Sheppard, the criminal who became a hero after escaping the death-cells at both New Prison and Newgate. Defoe's first biography was the standard short pamphlet. But after Sheppard's final capture, a sensational account appeared, allegedly written by Sheppard himself. The pamphlet, almost certainly by Defoe, is hardly rooted in reality. Defoe's journalistic style and willingness to play with the boundaries of truth would heavily influence the mystery genre for centuries to come.

The Literary Detective Makes His Debut

In Defoe's time and before, people focused on the criminal, making him (for the criminal was almost always male) a sort of anti-hero. That began to shift toward the end of the eighteenth century, as people  took more interest in the figures who were solving the crimes. The last significant work with a criminal as hero perfectly embodies this shift. French criminal Francois Eugene Vidocq published Memories (1828-1829), a memoir about his own exploits. Vidocq recounts how he repented and became a police informant, eventually coming to hold the post of Chef de la Surete. The book would influence authors like Victor Hugo and Honore de Balzac. It would also mark a new era for the crime novel, one where the protagonist is not a criminal, but a detective or other agent of the law.

took more interest in the figures who were solving the crimes. The last significant work with a criminal as hero perfectly embodies this shift. French criminal Francois Eugene Vidocq published Memories (1828-1829), a memoir about his own exploits. Vidocq recounts how he repented and became a police informant, eventually coming to hold the post of Chef de la Surete. The book would influence authors like Victor Hugo and Honore de Balzac. It would also mark a new era for the crime novel, one where the protagonist is not a criminal, but a detective or other agent of the law.

Yet the first modern detective novel would not emerge from France or England, but from America. Known as the father of horror, Edgar Allan Poe also created Auguste C Dupin in "The Murders on the Rue Morgue" in 1841. With "Rue Morgue," Poe also introduced the "locked room" style so indispensable to mystery writers, the scenario in which a murder takes place in an apparently sealed enclosure. The story was so successful, Poe continued Dupin's exploits in "The Mystery of Marie Roget" (1842) and "The Purloined Letter" (1845). With these tales, Poe was the first author to focus on the workings of the criminal mind.

Poe owes a great debt to both Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins. Dickens wove mystery and suspense into novels like Bleak House (1853), and his Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) remains the ultimate unsolvable mystery, as Dickens died before completing it. His friend Collins wrote The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868), which many consider the first true English detective novel. In his 1858 essay "The Unknown Public," Collins argues that the new generation of readers craved books that reflected their own place in society. As rising literacy rates met with more leisure time, interest in mystery novels veritably exploded during Collins' time.

It 1878, Anna Katherine Green became the first woman to write a detective novel with her The Leavenworth Case. Green introduced the elements of detection later used by writers of the English country house murder school during the 1920's. It wasn't until 1887 that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created Sherlock Holmes for "A Study in Scarlet." Doyle, an avid spiritualist, perhaps ironically was the first to turn solving crimes into a science that required the keenest deduction and unwavering devotion to reason.

The Golden Age of Mystery Fiction

By the 1920's the British mystery novel had attained unprecedented popularity. They tended to be set in small villages, with heroes who hailed from faintly aristocratic families. Exotic poisons or expensive letter openers were the murder weapons of choice, and there were plenty of red herrings to throw off the investigator. Despite the rather formulaic nature of these novels, readers clamored for them. The mystery novel had reached its Golden Age.

The Golden Age of Mystery Fiction refers not only to a time period, but also to a specific style, or rather a prescribed format with little variation. Agatha Christie quickly became synonymous with the Golden Age. She brought legendary detective Hercule Poirot to life in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920). Christie initially had trouble finding someone to publish the book. [A collecting note: Only 2,000 copies were printed in the first run; today hardback copies of this book in fine condition fetch quite tidy sums among rare book collectors. In contrast, the 1975 Curtain had about 10,000 copies in its first run, making it significantly less scarce on the market. Seasoned collectors know that as with many authors, Christie's earliest works are generally the most desirable.]In 1923, only a few short years after the world met Poirot, Dorothy L Sayers brought us another influential detective. Lord Peter Wimsey's unmistakable style and intelligence made Sayers one of the most popular authors of the day.

During the height of the Golden Age, London publisher Allen Lane decided to capitalize on the booming market. He obtained limited rights to hardback books by Sayers and other prominent mystery writers. In 1935, Lane issued new paperback copies of ten popular mystery titles. The public's appetite for these accessible copies proved insatiable, and Lane quickly expanded to seventy titles within the year. Called "penguins," these novels were much more affordable could be found in department stores, where most people shopped at the time. Collectors often seek these paperbacks for their libraries, aiming to obtain both the first hardback and the first paperback copy of each title. Because paperbacks are made with cheap materials and often subject to rough use, they can be difficult to find, adding another dimension to collecting mystery novels.

The Hard-Boiled Detective Novel

The American mystery novel also took its own turn in 1920. That year, author HL Mencken and critic George Jean Nathan launched Black Mask magazine. Originally dedicated to all kinds of adventure stories, the magazine eventually published only detective stories. It was on these pages that the hard-boiled detective story emerged. Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were frequent contributors. Eric Stanley Gardner, who got his start in Black Mask, went on to create the character Perry Mason. The iconic detective would appear in numerous novels and films, along with a television series that debuted in 1957 and ran for ten seasons.

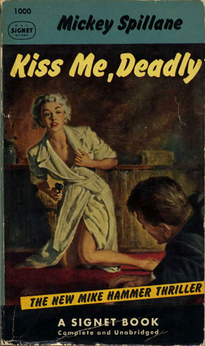

In the 1940's, mystery took a new turn, first with the advent of the police procedural. This sub-genre focuses on the perspective of the police and coincided with the rise of television. And in 1947, Mickey  Spillane published I the Jury, featuring the notorious detective Mike Hammer. Though Spillane's gritty, violent stories got unenthusiastic reviews from critics, the public loved them. His mostly male readers bought over six million copies of I the Jury alone, making Spillane the best-selling mystery writer in history at the time.

Spillane published I the Jury, featuring the notorious detective Mike Hammer. Though Spillane's gritty, violent stories got unenthusiastic reviews from critics, the public loved them. His mostly male readers bought over six million copies of I the Jury alone, making Spillane the best-selling mystery writer in history at the time.

Mystery novels also began to make their way into children's literature. Series like Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys were often written by corporate authors and followed variations on the formula so successfully used by the English country house murder school--though the crimes were generally much less shocking than murder. Today, these children's mystery series remain a popular focus for adult collectors.

Today, the mystery genre remains a thriving one. "New arrivals" to mystery writing include beloved authors like Sue Grafton, Robert B Parker, PD James, and Dick Francis. All these figures are popular among readers and collectors alike. Though the mystery novel has changed over time, it never fails to fascinate us.