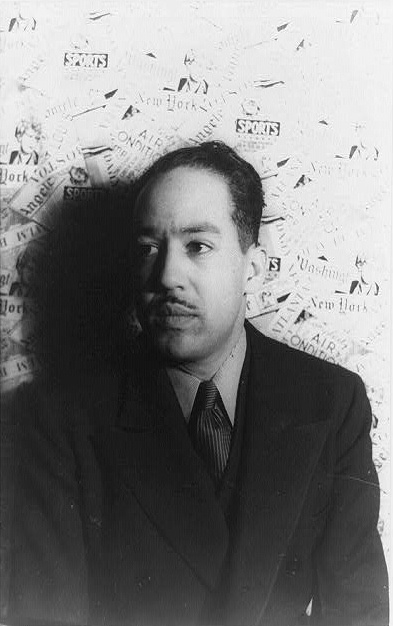

In his seminal 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” then-burgeoning poet, essayist, novelist, playwright, and all-around giant of American letters Langston Hughes argued passionately that Black writers across the world should be proud of their racial and cultural heritage. He says, towards the essay’s conclusion, “The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too.” Even then, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, it’s hard to imagine that Hughes knew the momentous impact he would make merely by following his own advice.

Not only does Hughes stand today as one of the most successful weavers—along with perhaps Zora Neale Hurston—of African American folk music and art with the literary and poetical tradition of earlier writers like Walt Whitman, but he also spent decades as a champion of the work of other Black artists, from his fellow Harlem Renaissance writers to Alice Walker. Here is a guide to approaching his inimitable oeuvre.

Not only does Hughes stand today as one of the most successful weavers—along with perhaps Zora Neale Hurston—of African American folk music and art with the literary and poetical tradition of earlier writers like Walt Whitman, but he also spent decades as a champion of the work of other Black artists, from his fellow Harlem Renaissance writers to Alice Walker. Here is a guide to approaching his inimitable oeuvre.

Selected Poems of Langston Hughes

It may seem like a bit of a cop out to begin with Hughes’ selected verse instead of highlighting an individual collection, but in this case it was Hughes himself who handpicked the poems, so who are we to argue? More than that, it pairs his most famous works (like “The Negro Sings of Rivers,” the poem that first catapulted him to acclaim when it was published in The Crisis in 1921; “I, Too” (1926), which acts a kind of reverent rebuff to Walt Whitman; and 1926's "The Weary Blues") with some of his most daring (like Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951), reproduced in its entirety, which boldly incorporates elements of bebop, ragtime, and blues to offer an almost cinematic meditation on post-war Harlem). The poems span his 40+ year career and give readers more than a good sense of the deft hand with which Hughes would consistently blend elements of jazz and Black folk music with the poetic forms of the day. Interestingly, however, the collection often makes a point of avoiding the subject of communism, in spite of the many politically charged, radically-socialist poems the communist-leaning Hughes wrote in the 1930s. Given the year of publication (and the fact that Hughes testified before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations), we might go ahead and blame Joe McCarthy.

The Ways of White Folks

While Hughes is most often remembered for his poetry, he wrote a number of texts across other genres, including fiction, drama, and non-fiction, many of which are more than worth reading.

While Hughes is most often remembered for his poetry, he wrote a number of texts across other genres, including fiction, drama, and non-fiction, many of which are more than worth reading.

In fiction, for instance, The Ways of White Folks (1934) was hailed by The New York Times on the occasion of its reprinting in 1996. Inspired by his time spent in Carmel, California, the collection of 14 vignettes describes everyday encounters between black and white citizens. The Times credited the influence of D.H. Lawrence, and Hughes’ erstwhile socialism, for the power that suffused Hughes’ story cycle, claiming that they represented the apex of his short-fictional prowess.

Also noteworthy is Hughes’ debut novel, Not Without Laughter (1930), which was released to some acclaim, and remains a closely observed, character driven work displaying the same rhythmic qualities as Hughes’ poetry.

Mule Bone

If after reading Hughes’ Selected Poems (1959) and a sampling of his fiction (and the essay cited above), you’re craving more of his writing, the logical thing to do is probably to upgrade to his Collected Poems (1994), which obviously contains all of his lauded poetical efforts. If, for some reason, you’re disinclined to do so (or, not unreasonably, you need even more Hughes), you might turn to his dramatic works. Mule Bone (1930), in particular, is worth a read if only as a curiosity—because as curiosities go, it is especially curious.

Co-written with Zora Neale Hurston in 1930 based on a folk tale she had collected as an anthropologist, it required just a few finishing touches when Hurston decided, seemingly without explanation, to cut off virtually all communication with Hughes. It has been theorized that Hurston was hoping to maintain a relationship with a patron that Hughes had just fallen out with, but, whatever the reason, Hurston tried later that year to copyright the work in her own name. Hughes strongly objected, and eventually succeeded in attaching his name to the copyright, but by then the controversy had put a damper on any hopes of getting the work produced. The play eventually debuted on Broadway in 1991, where it garnered mostly negative reviews.