We were fortunate enough to interview David Pascoe of Nawakum Press--a publisher of unique, handcrafted books. David has collaborated with an impressive group of writers and artists, including Barry Moser and Pulitzer Prize winning poet, Paul Muldoon. His books have been collected by many important institutions, including the Library of Congress, Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book Library, Stanford University's Cecil H. Green Library, Harvard University's Houghton Library, and many others. In this interview, David shares with us the story of Nawakum Press: its origins, inspirations, and notable collaborations.

Books Tell You Why: For those of our readers unfamiliar with Nawakum Press, could you give us a quick overview of your work and focus areas?

Books Tell You Why: For those of our readers unfamiliar with Nawakum Press, could you give us a quick overview of your work and focus areas?

David: Nawakum publishes fine press and artist’s books--about one or two titles a year. Small editions, usually less than 50 copies. There’s no formula for what gets published. The subject matter tends to be all over the place. I like it that way. Where else would you find Jorge Luis Borges, Rachel Carson, Irish poet Paul Muldoon, and Herman Melville shelved together? While there is always a project in the works, I don’t always know where the next one will come from.

Books from Nawakum are letterpress printed and hand bound. Artists contribute original artwork for each book. Sometimes the art drives the writing but mostly it is the other way around. Publishing books is sort of a compulsion for me. Most of the work is modern literature, and there is a lot of poetry. My focus these days is more on new work. Someone told me once that literature of place, which I enjoy, wasn’t appropriate for fine press. That is partly why I publish it as well.

I’m very lucky. Nawakum is a publishing press with no equipment. I get to collaborate with some of the best book artisans working today. And with talented artists who create compelling artwork. In the past I owned equipment, a Colt’s Armory printing press I helped put back together, and a Chandler & Price treadle press. I have handset type and all the rest. But now I let much more talented people do the work. It is a privilege actually to be collaborating with such smart and talented folks, who are so good at what they do. They are also some of the stories I wish to tell.

Books Tell You Why: What sets Nawakum Press apart from other fine press? What makes your publications unique?

David: Well, like a lot of fine presses today I am interested in creating something unique, beautiful and lasting. I look to the tradition of fine printing for inspiration, while still trying to push the envelope. Each of my books varies according to whose input and expertise was brought to bear in each collaboration. So there is no uniform look or feel to the editions, since a different mix of people contribute each time. Nawakum books are of the highest quality in construction and materials, and tend toward understated elegance. Uncomplicated works fine. Things do not need to be overly fancy or complex. But they must be well thought out and well put together. I am always searching for an aesthetic that is pleasing to the eye and to the touch. I want the books to be handled, and to be read.

Books Tell You Why: How did Nawakum Press begin? How did you choose its name?

David: It began in the garage print shop of The Feathered Serpent Press in San Anselmo, California in 1979. Don Kelley was teaching bookmaking classes at the time. I signed up that summer. The place was crammed with presses and metal type and all the equipment one needed. While Don was printing miniature books for Stanley Marcus I was learning how to hand set type, print, and bind books. Nawakum Press was born in that garage, and soon I bought my own presses and moved them to Sebastopol.

Nawakum was reborn in 2009 after a very long hiatus. The equipment had been sold decades earlier but the name had remained. I had gone on to manage commercial printing projects to support a growing family. My work for advertising agencies took me to commercial printers in the Twin Cities area, where print runs often ran into the millions. Coming back to letterpress, on a more intimate scale, was like coming home again. And I wanted to finish what I had only started all those years before.

Nawakum was reborn in 2009 after a very long hiatus. The equipment had been sold decades earlier but the name had remained. I had gone on to manage commercial printing projects to support a growing family. My work for advertising agencies took me to commercial printers in the Twin Cities area, where print runs often ran into the millions. Coming back to letterpress, on a more intimate scale, was like coming home again. And I wanted to finish what I had only started all those years before.

The Native American word "nawakum," originating in the Pacific Northwest, means gently flowing water. I chose it for a press name for a couple of reasons. I grew up in that part of the country so it was meaningful for me to adopt a name that went back to my roots. And also I wanted a name that came from a place that honored storytelling, held a reverence for the land and the water that nourished it.

Books Tell You Why: You collaborate with some very talented people. Could you tell us more about those relationships and how they began?

David: When I wanted to get back into fine press publishing it didn’t take long to figure out who some of the most accomplished players were. Like any field of endeavor, the closer you look the smaller that world gets. I started locally, so letterpress printers like Patrick Reagh and Norman Clayton were clearly people I wanted to meet and work with. I simply showed up with projects and they got onboard.

David: When I wanted to get back into fine press publishing it didn’t take long to figure out who some of the most accomplished players were. Like any field of endeavor, the closer you look the smaller that world gets. I started locally, so letterpress printers like Patrick Reagh and Norman Clayton were clearly people I wanted to meet and work with. I simply showed up with projects and they got onboard.

Patrick’s print shop, complete with monotype casting equipment, is less than 20 minutes from where I live. His archives are held at The Clark Library and he has won numerous design awards. So I am lucky to have such a resource close by. Not to mention Patrick’s well-groomed lawn bowling court sitting next to his printing barn. John DeMerritt was also someone nearby, an Emeryville bookbinder who was mentioned often in colophons of books I admired. I looked him up, was even more impressed by what he did, and we soon started working together.

Peggy Gotthold of Foolscap Press introduced me to Craig Jensen from San Marcos, Texas at a Codex book fair. She took me by the hand to his table and said you need to meet this guy. And that opened up another important bookbinding relationship. I’ve stayed at Craig’s home studio a number of times, and his wife, Ann, is an official member of the Nawakum “focus group.”

When grappling with a production issue I sometimes ask those I am working with “What does the focus group think?” and they know I am referring to their spouses. Spouses are often very insightful, and can cast an important swing vote if necessary. Craig and I have collaborated on three editions now, and as with everyone, I contact him as early as possible in the process. That way I can’t head too far down a misguided path.

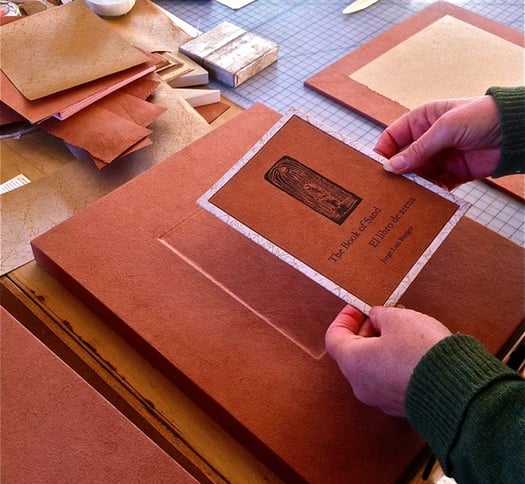

I had admired Peggy and Larry’s work at Foolscap for a long time when I approached them about helping produce an artists’ book of a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. The story is about a retired librarian in Buenos Aires who gets a knock on his apartment door late one night. He opens the door to find a used book salesman with bibles and other curiosities. The librarian buys a magical book, with no beginning and no end, and it drives him nearly insane.

I had admired Peggy and Larry’s work at Foolscap for a long time when I approached them about helping produce an artists’ book of a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. The story is about a retired librarian in Buenos Aires who gets a knock on his apartment door late one night. He opens the door to find a used book salesman with bibles and other curiosities. The librarian buys a magical book, with no beginning and no end, and it drives him nearly insane.

I needed a very creative approach to pull this book off, and starting with sketches and then rough dummies we worked our way through to a fitting artists’ book solution. Thomas Wood’s etchings sit splendidly within the unique framework crafted at the Foolscap shop in Santa Cruz.

Some early work of Barry Lopez intrigued me. I ended up asking Barry Moser to participate in the project and he accepted. Turned out he had met Lopez earlier at Smith College and they had talked about maybe doing a project together. So voilà. I had the privilege of collaborating with both of these guys, which was a great pleasure. At first Lopez would communicate with me only through typewritten postcards. I thought this was very special and have saved them all. He now has made the digital leap. Through Moser, I met letterpress printer Arthur Larson of Horton Tank Graphics in Massachusetts, who Barry said printed his blocks like nobody else could. As well as printing for Moser’s Pennyroyal Press, Art had printed 30 books for Leonard Baskin’s Gehenna Press. He is amazing. We have completed two Moser projects together, with a third one on the horizon.

And so it went, and still goes. Over time I have discovered yet more talented people who contribute their expertise and vision to Nawakum books. Their input is meaningful and essential. Working with authors, with artists, binders, and papermakers all requires a slightly different approach. It helps that they are so accomplished at what they do. Recently, I found a blacksmith to work with me. I needed a hand hammered piece of copper to use on the cover of a clamshell box. He stepped right in and hit the mark, and was surprised his work would be embedded in Japanese silk. If I can somehow make sure these very creative people are enjoying what they are doing, then the best work always seems to follow.

Books Tell You Why: What is the process of creating books at Nawakum Press? What does it take for an idea to become reality?

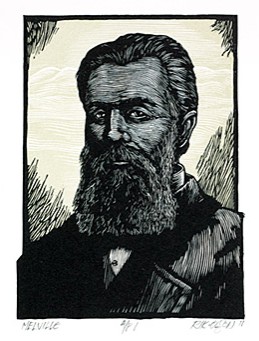

David: For an idea to become a Nawakum book, it had better be worth publishing in the first place. If I need to get permissions for the literature then that has to be negotiated. If working with a living author, they need to get onboard what I am trying to accomplish. When I approached John Bryant, a leading Melville scholar, to write an introduction to Melville’s sketch Norfolk Isle and the Chola Widow, he was happy to oblige. So happy that he wrote a wonderful introduction that just happened to be twice as long as I had asked for, and the same length as the story itself. So we needed to work together to pare it down to its essentials. With ideas, I am the frequency holder. I am happy to bend as collaboration takes over, but I also need to keep the books on track.

The artwork for any book is critical for me, so an artist of high caliber has to be willing to sign on. I introduce the concept behind the project and see if it resonates with them. In the case of the artwork coming first, I need to like and identify with it, and be willing to build out the idea based on literature that is the artwork’s equal. Others need to be interested, or preferably, excited about the idea. This is not a one-man show so resonance throughout all those participating is important. Once I am lucky enough to have the people sign on whom I want involved, I need to get them thinking about issues right away. What restrictions are we under, is the direction on this or that part viable, and where can we experiment? And I need to know when to get out of the way for an idea to keep growing, and when to bird dog the process. The idea slowly matures, defines and redefines itself, and eventually emerges as a book.

The artwork for any book is critical for me, so an artist of high caliber has to be willing to sign on. I introduce the concept behind the project and see if it resonates with them. In the case of the artwork coming first, I need to like and identify with it, and be willing to build out the idea based on literature that is the artwork’s equal. Others need to be interested, or preferably, excited about the idea. This is not a one-man show so resonance throughout all those participating is important. Once I am lucky enough to have the people sign on whom I want involved, I need to get them thinking about issues right away. What restrictions are we under, is the direction on this or that part viable, and where can we experiment? And I need to know when to get out of the way for an idea to keep growing, and when to bird dog the process. The idea slowly matures, defines and redefines itself, and eventually emerges as a book.

Books Tell You Why: What have been your biggest challenges?

David: Staying fresh with new ideas can be challenging. Finding bookcloth that hasn’t graced the covers of 100 other fine press books is tough. Pricing books so that it makes sense is daunting at times. Sometimes as few as three or four people are involved in a project, and sometimes more than a dozen. They all have their own schedules, but I also have mine. So some finessing, and cajoling, pleading and praising come into play. Typos can be a curse. They have a life of their own. I once lived on a sailboat in the tropics and no matter what you put in place to keep the bugs out they would find their way through. Typos are the no-see-ums of the tropics. Finding buyers for the books is always an interesting challenge. From a financial standpoint it is critical, both for the Press and for all those I wish to support. But these books also end up feeling like my children. I care a lot about finding good homes for them, where they will be appreciated and taken care of.

Books Tell You Why: How do you choose your projects? Do you have any favorites?

Books Tell You Why: How do you choose your projects? Do you have any favorites?

David: Sometimes I choose them, and sometimes they choose me. In the beginning I would come up with all the ideas and look for help in executing them. The writing needed to be something special, and I had to be enthusiastic about the subject matter. Project cycles can run into years and that enthusiasm helps sustain me moving forward. These days, the whole process is much more organic and collaborative.

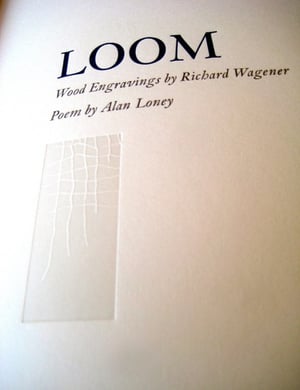

Richard Wagener of Mixolydian Editions, a friend and marvelous wood engraver, asked me to look at some of his new work a while back. It was a departure from what he was known for, and he had an idea of what could be done with it. I listened to what he had in mind and jumped in right away. LOOM was the co-publication that came from it. We went to Melbourne, Australia to launch the edition, where the poet who wrote to Richard’s images, Alan Loney, was helping shepherd Codex Australia along.

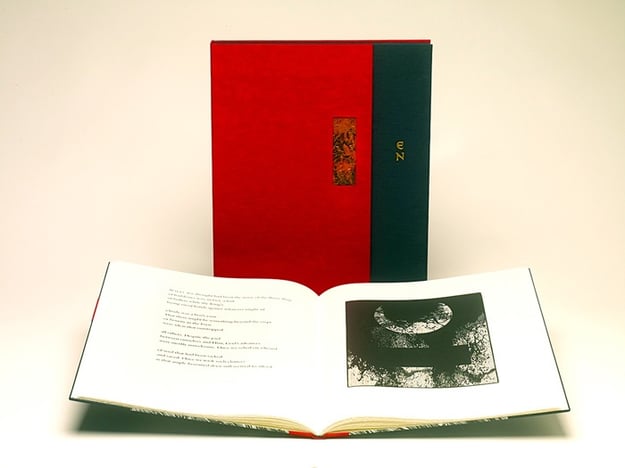

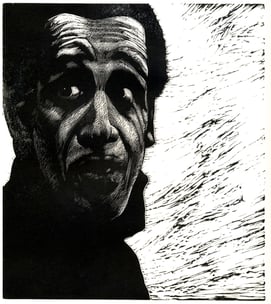

Barry Moser and I had done a book together some time back with short stories from Barry Lopez. We became friends and were staying in touch when he mentioned some abstract images he was working with on his computer. I asked to see what they looked like and he sent a couple “cyber sketches” over. I was stunned. First because they were so uncharacteristic for him, and also the images were dark and hauntingly beautiful. The result was our Encheiresin Naturae, having pulled onboard poet Paul Muldoon. Moser and Muldoon had first met when the poet had wandered into the Smith College print shop to see what was going on.

As for favorites, I don’t really have any. Each one is special in its own way. I feel very attached to some though. Mostly because of what obstacles had to be overcome for them to see the light of day. The serendipitous events that took me off a misguided path I was on, and onto a better one. Hand-made paper that dropped into my lap at the last possible moment that I hadn’t even considered. A literary agency that waived any fees for publishing the work because they liked what I was intending to do. The calligrapher whose work crossed over 2 pages before she ran out of ink, when we needed to print 3 pages of her work at a time. Then there was the author’s widow who first said no, said no again, and then said yes.

Books Tell You Why: What projects are currently in the works at Nawakum Press? What are your plans for 2015?

Books Tell You Why: What projects are currently in the works at Nawakum Press? What are your plans for 2015?

David: Currently, I am working with Richard Wagener on another co-publication titled Trading Eights, The Faces of Jazz. Richard will be printing from the blocks of wood engraver, James Todd, who has agreed to lend us blocks of jazzmen portraits he did over a 20-year span. They have never been published in book form. Ted Gioia, the American jazz critic, and one of the founders of Stanford University’s jazz studies program, has written an essay for us on jazz from the 50s and 60s. His brother, Dana Gioia, the American poet, who also served as the Chairman of the National Endowment of the Arts, is writing jazz poetry for the project. We are hoping to have it completed in time for the Oxford Fine Press Book Fair in 2015.

A big thank you to David for sharing with us the story of Nawakum Press. Click below to view some of his outstanding work or share your reactions with him in our comments section.