Controversial Nobel Prize in Literature winner Bob Dylan admitted to being flabbergasted when he learned of the honor that’s lately been bestowed on him—but at least he managed to compare himself to Shakespeare in the process. The comparison, though, was an interesting one, and one that takes up the question of how we should approach the Bard’s writing. Dylan’s assertion was that he has never thought about whether his songs are ‘literature’ and that Shakespeare probably would have been in the same boat regarding his plays. Dylan says, imagining Shakespeare’s thoughts leading up to the original production of Hamlet (1599), ““Are there enough good seats for my patrons?” “Where am I going to get a human skull?” I would bet that the farthest thing from Shakespeare’s mind was the question “Is this literature?””

For Bob Dylan, Shakespeare is more interested in being a folk artist—telling good stories and captivating his public (mostly comprised of the middle and working classes)—than he is in participating in ontological debates over the nature of his art. This isn’t a new way of viewing Shakespeare, but it’s also not necessarily the dominant cultural narrative around him. For many, the default way to approach the 400 year old English poet and playwright was solidified in the Romantic era, with a little help from Charles Lamb.

For Bob Dylan, Shakespeare is more interested in being a folk artist—telling good stories and captivating his public (mostly comprised of the middle and working classes)—than he is in participating in ontological debates over the nature of his art. This isn’t a new way of viewing Shakespeare, but it’s also not necessarily the dominant cultural narrative around him. For many, the default way to approach the 400 year old English poet and playwright was solidified in the Romantic era, with a little help from Charles Lamb.

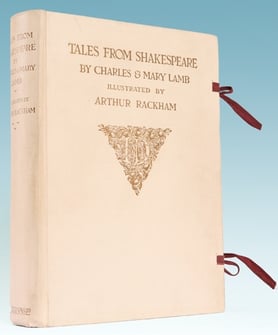

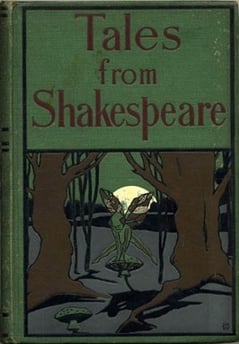

Charles (and his sister Mary) Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare (1807), which was comprised of fairy-tale like retellings of the Bard’s greatest hits, was frequently the earliest introduction to Shakespeare for children growing up in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. This was naturally a significant pulpit from which to espouse his ideas on Shakespeare, but Lamb was also a noted critic, made perhaps especially influential as such by his friendships with William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In that capacity, he famously asserted that King Lear (1606) "is essentially impossible to be represented on the stage."

By popularizing the notion that some of Shakespeare’s work is best read rather than seen, Lamb tries to decouple Shakespeare’s art from its medium. In particular, when he claims that Lear, the character, is impossible to act (comparing the job to the task of acting out the Satan of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), while glossing over the fact that Milton’s work was never meant to be represented on stage the way Shakespeare’s was), he asserts Shakespeare’s true legacy as one of poet par excellence—a literary idol meant to be consumed the way Romantic poetry is consumed, rather than a folk hero catering to those that desire performance. Lamb’s Shakespeare, unlike Dylan’s, would have had no trouble thinking of his work in literary terms.

Tales from Shakespeare by the very fact of its existence helps to further Lamb’s viewpoint. After all, the tales are meant to be read, not performed (though one wonders how frequently they were read aloud by parents), and the book trains its readers to think of Shakespeare in those terms. But because so many decisions needed to be made about how best to narrate the action of works that are otherwise acted, the retellings also gives clues as to the way that Lamb interprets particular plays, sometimes with odd results. In Lamb’s version of Hamlet, for instance, the issue of the titular Danish prince’s madness naturally arises.

Tales from Shakespeare by the very fact of its existence helps to further Lamb’s viewpoint. After all, the tales are meant to be read, not performed (though one wonders how frequently they were read aloud by parents), and the book trains its readers to think of Shakespeare in those terms. But because so many decisions needed to be made about how best to narrate the action of works that are otherwise acted, the retellings also gives clues as to the way that Lamb interprets particular plays, sometimes with odd results. In Lamb’s version of Hamlet, for instance, the issue of the titular Danish prince’s madness naturally arises.

While scholars have argued for centuries over whether Hamlet’s madness is real or feigned, Lamb is inclined to have his crazy and eat it, too. He tells his young, impressionable readers that Hamlet is made partially insane by his meeting with his father’s ghost, and that he opts to pretend to be fully (rather than only somewhat) unhinged in order to arouse less suspicion (the logic being that a wholly insane person wouldn't be able to pose a real threat to Claudius). And Hamlet, rather than battling deep internal conflict, is seen to just be slow moving. Rather than debating whether to kill his uncle or himself based on the shifting reality of the situation (the famous ‘To be, or not to be,’ soliloquy does not make an appearance, nor does ‘Alas, poor Yorick!’, in spite of Lamb’s ostensible commitment to including Shakespeare's original language when possible), Hamlet merely forgets his purpose, or becomes distracted, until fate conspires to remind him again.

Some of the material in Lamb’s King Lear is equally odd. Or, at least, in his retelling, Lamb was equally willing to gloss over the well-documented ambiguities of the text. Ironically, this forces him to make exactly the sorts of decisions that actors and directors have to make when they stage the plays. Lamb has to give explicit motivation and a specific tone to Cordelia as she tries to reveal the hypocrisy of her sisters, just as he has Lear apportion a third of kingdom to Goneril “in a fit of fatherly fondness,” rather than as the result of measured, pre-determined decisions that are upended by a set of ceremonial formalities gone awry (as scholars like Richard Strier have suggested). Perhaps the strangest maneuver in Lamb’s version, however, comes at the end. He concludes the tale by saying:

Some of the material in Lamb’s King Lear is equally odd. Or, at least, in his retelling, Lamb was equally willing to gloss over the well-documented ambiguities of the text. Ironically, this forces him to make exactly the sorts of decisions that actors and directors have to make when they stage the plays. Lamb has to give explicit motivation and a specific tone to Cordelia as she tries to reveal the hypocrisy of her sisters, just as he has Lear apportion a third of kingdom to Goneril “in a fit of fatherly fondness,” rather than as the result of measured, pre-determined decisions that are upended by a set of ceremonial formalities gone awry (as scholars like Richard Strier have suggested). Perhaps the strangest maneuver in Lamb’s version, however, comes at the end. He concludes the tale by saying:

“How the judgment of Heaven overtook the bad earl of Gloucester, whose treasons were discovered, and himself slain in single combat with his brother, the lawful earl; and how Goneril's husband, the duke of Albany, who was innocent of the death of Cordelia, and had never encouraged his lady in her wicked proceedings against her father, ascended the throne of Britain after the death of Lear, is needless here to narrate; Lear and his Three Daughters being dead, whose adventures alone concern our story.”

This may be seemingly innocuous by itself. Though the ascension of Albany at the play’s end was important enough for Shakespeare to make a point of it, it’s true that he does not actually go out of his way to depict it. What makes the passage odd is the fact Lamb makes an almost identical move in Hamlet, in which he concludes the play with the prince’s death and never once deigns to mention Fortinbras and his imminent takeover of Denmark. In these two plays at least, Shakespeare’s interest in what happens after tragedy should be apparent—the plays make a point of clueing readers and audience members in to the new realities that will arise in the worlds that they’ve been observing following their seeming annihilations. For theorist Frank Kermode, these moments could be read as repudiations of the closed-off worlds and apocalyptic tone of some tragedies, the Greeks in particular. “Life goes on,” Shakespeare seems to assert, “the end of the world is not upon us; these stories do not exist in a vacuum.”

This may be seemingly innocuous by itself. Though the ascension of Albany at the play’s end was important enough for Shakespeare to make a point of it, it’s true that he does not actually go out of his way to depict it. What makes the passage odd is the fact Lamb makes an almost identical move in Hamlet, in which he concludes the play with the prince’s death and never once deigns to mention Fortinbras and his imminent takeover of Denmark. In these two plays at least, Shakespeare’s interest in what happens after tragedy should be apparent—the plays make a point of clueing readers and audience members in to the new realities that will arise in the worlds that they’ve been observing following their seeming annihilations. For theorist Frank Kermode, these moments could be read as repudiations of the closed-off worlds and apocalyptic tone of some tragedies, the Greeks in particular. “Life goes on,” Shakespeare seems to assert, “the end of the world is not upon us; these stories do not exist in a vacuum.”

Now, of course, Lamb’s versions of Shakespeare are often objectively delightful. But are his attempts to place certain of Shakespeare’s tragedies in a vacuum related to his preference for reading them as literature over experiencing them in performance? The boundaries between art and real life may, after all, be more obviously porous on the stage, whereas reading can further the illusion of a separation between reading (an abstract activity in the way that literature can be an abstract concept) and, say, social and political action. On the other hand, the pleasures of reading Shakespeare can hardly be denied. Maybe Bob Dylan can shed a little more light on the subject when he (hopefully) gives his Nobel lecture.

Source here.