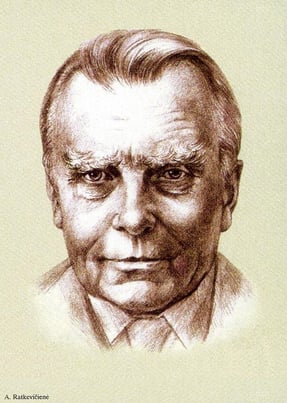

Czesław Miłosz was born in 1911 in Poland to an ethnically Lithuanian civil engineer and a Polish noble. Miłosz was raised in Lithuania, and though it caused much controversy in his life, he would never ally himself formally with either Poland or Lithuanian, saying that he was born in Poland, and was therefore technically Polish, but that he was raised with the spirit of the Lithuanian people and could not deny that part of himself. Interestingly, Miłosz's literary and political efforts would cause him to remain on the fringe, only recognized in and by his homeland later in his life.

Czesław Miłosz spoke Polish, Lithuanian, French, English, and Russian, though he composed his works exclusively in Polish. He was not as fluent in Lithuanian in the later part of his life. In fact, he even went so far as to get a language tutor to instruct him on how to improve his fluency, as he wanted to become more in touch with the language of his childhood. He stated once that Lithuanian was important to him because he suspected it might be the language they speak in heaven.

Czesław Miłosz spoke Polish, Lithuanian, French, English, and Russian, though he composed his works exclusively in Polish. He was not as fluent in Lithuanian in the later part of his life. In fact, he even went so far as to get a language tutor to instruct him on how to improve his fluency, as he wanted to become more in touch with the language of his childhood. He stated once that Lithuanian was important to him because he suspected it might be the language they speak in heaven.

While studying law, Miłosz reconnected with a French Lithuanian cousin, poet Oscar Miłosz. His cousin proved to me a major influence on the young writer. He formed a poetry group and though he ultimately graduated from law school, he shifted his focus to literary pursuits and published his first book of poetry, Three Winters, shortly after, while spending a fellowship year in Paris. He returned to Poland before World War II and lived in Warsaw for the duration of the war. Miłosz did not enlist in the army. His own efforts during the war however, were considerable, though not related to the military. Throughout the war, Miłosz and his brother financed and aided numerous Warsaw Jews, for which Miłosz received a medal, the Righteous Among the Nations, from Israel in 1989.

After World War II, he worked for the People's Republic of Poland and in 1953 published his seminal book, The Captive Mind, about the plight of intellectuals stifled under the rule of totalitarianism. The work has become crucial in political science classes studying the Cold War and totalitarianism. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the success of the book, Miłosz was repeatedly censored and faced numerous attacks against his works. As a result, he defected to France, seeking political asylum—an act that garnered much criticism.

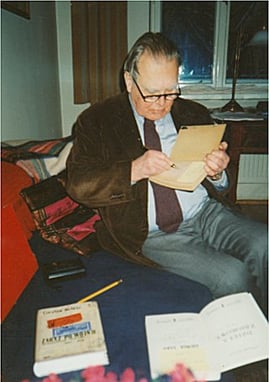

In 1960, Miłosz moved to the United States, where he taught Slavic Languages at UC Berkeley. Not long after, he received both the Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the Nobel Prize in Literature, two awards which for the first time, brought him to the attention of the Polish, who had been denied exposure to his work due to the censorship of his leftist politics and Lithuanian sympathies. When the Iron Curtain fell, Miłosz was finally able to return home to Poland, where he lived when he was not staying in Berkeley.

In 1960, Miłosz moved to the United States, where he taught Slavic Languages at UC Berkeley. Not long after, he received both the Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the Nobel Prize in Literature, two awards which for the first time, brought him to the attention of the Polish, who had been denied exposure to his work due to the censorship of his leftist politics and Lithuanian sympathies. When the Iron Curtain fell, Miłosz was finally able to return home to Poland, where he lived when he was not staying in Berkeley.

Upon his death, he was buried in the Skałka Roman Catholic Church in Krakow, though it was much debated. Protesters complained he was anti-Catholic and against Poland. Pope John Paul II spoke up on his behalf, and protesters were quieted for the most part. In 2011, Yale hosted a symposium and exhibit on the importance of his work titled Exile as Destiny: Czesław Miłosz and America. His work remains the object of study and is lauded for both its political and literary relevance.

Image source.