John Steinbeck has become a central figure in the American literary canon. A winner of the National Book Award, Pulitzer Prize, and Nobel Prize, Steinbeck certainly has the accolades to justify that position. But Steinbeck's detractors--including members of the Swedish Academy--doubted the legendary author's merits, and Steinbeck himself didn't believe he was worthy of the Nobel.

Grapes of Wrath Sparks Controversy

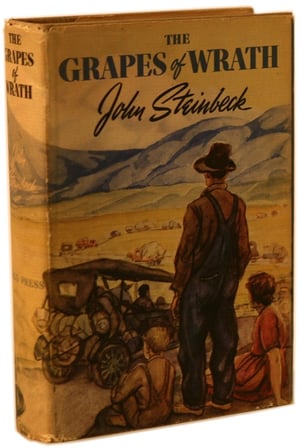

The Grapes of Wrath is widely considered to be Steinbeck's best work, though other works like Winter of Our Discontent and Of Mice and Men have definitively shaped the world of literature as well. When Grapes of Wrath was published in April of 1939, it met with immediate praise--and harsh criticism. The book starkly portrays the social injustices faced by the American underclass during the Great Depression. Steinbeck's portrayal of wealthy farmers, bank owners, and capitalism are hardly complimentary, which raised considerable ire across the country. In some places, copies of Grapes of Wrath were even burned.

The Grapes of Wrath is widely considered to be Steinbeck's best work, though other works like Winter of Our Discontent and Of Mice and Men have definitively shaped the world of literature as well. When Grapes of Wrath was published in April of 1939, it met with immediate praise--and harsh criticism. The book starkly portrays the social injustices faced by the American underclass during the Great Depression. Steinbeck's portrayal of wealthy farmers, bank owners, and capitalism are hardly complimentary, which raised considerable ire across the country. In some places, copies of Grapes of Wrath were even burned.

A London Times critic deemed Grapes of Wrath "one of the most arresting [novels] of its time." Meanwhile, the Newsweek review called it a "mess of silly propaganda, superficial observation, careless infidelity to the proper use of idiom, tasteless pornographical and scatological talk." The Associated Farmers of California dismissed the work as a "pack of lies" and "Communist propaganda."First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt defended the novel against allegations of exaggeration, but Steinbeck still received death threats. The FBI put him under surveillance. Steinbeck found the reaction--from both the public and the goverment--"completely out of hand."

Steinbeck had predicted such a reaction as he set out to write Grapes of Wrath. Knowing that the veracity of the book would come into question, he drew liberally from historical sources and documented his research in his writing journals. One of his most useful sources were the reports of Tom Collins, director of Arvin Migrant Camp in California (a number of which are available online through the National Archives). Steinbeck noted in his journal, "I need this stuff. It is exact and just the thing that will be used against me if I'm wrong."

Copies Fly from the Shelves

But controversy sells. The first hardback printing of Grapes of Wrath was quite large for the time: somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000. It became the bestselling book in America in 1939. By February, 1940 the novel was already in its eleventh printing, and more than 430,000 copies had been sold. That year, it remained one of the nation's top ten bestsellers. In May, 1940, Grapes of Wrath won the Pulitzer Prize, again boosting sales.

Almost as soon as the book was published, a movie adaptation came under consideration. Darryl F Zanuck of 20th Century-Fox bought the movie rights and assigned the project to his best director, John Ford. Ford was already known for his exceptional work on Westerns. Zanuck was worried that the movie would be plagued by the same same controversy as the book, so he hired private investigators to investigate conditions for migrant workers. What they saw corroborated Steinbeck's account. Zanuck moved forward with production.

The movie had an exceptional cast, with Henry Fonda as Tom Joad. Zanuck and Ford toned down some of the novel's politics and departed from the book in a few places. When it debuted in January 1940, the adaptation met with critical acclaim and was nominated for seven Academy Awards. Ford took the Oscar for best director, while Jane Darwell, who played Ma Joad, won the award for best supporting actress. Again, the movie helped to keep Grapes of Wrath on the bestseller list.

A Dubious Nobel Committee Decision

Fast forward to 1962. The Swedish Academy was trying to choose a Nobel laureate for literature. Steinbeck had previously been nominated eight times, largely because of Grapes of Wrath. But in every instance, another author with a more impressive body of work had been selected. This year, the committee had a difficult choice: none of the candidates seemed like clear winners. Henry Olsson, a committee member, wrote, "There aren't any obvious candidates for the Nobel prize, and the prize committee is in an unenviable position."

The committee eventually whittled down the list from 66 nominees to five candidates: Steinbeck, Robert Graves, Lawrence Durrell, Jean Anouilh, and Karen Blixen. Blixen passed away, rendering her ineligible. Anouilh was likely passed over because of his nationality; French poet Saint-John Perse had just won in 1960, and Jean-Paul Sartre (who won and declined the prize--in 1964) was seen as an up-and-coming prime candidate. The committee generally agreed that Durrell's work was not yet sufficient to merit a prize. And, according to an article in The Guardian, "Olsson was reluctant to award any Anglo-Saxon poet the prize before the death of Ezra Pound, believing that other writers did not match up to his mastery." That eliminated Graves, who was still seen as a poet despite having written several historical novels.

Thus Steinbeck remained. The Academy gave him the award for his "realistic and imaginative writing, combining...sympathetic humor and keen social perception." After he was named the winner, one Swedish newspaper called the choice "one of the academy's biggest mistakes." The New York Times inquired why the prize went to an author whose "limited talent is, in his best works, watered down by tenth-rate philosophizing." Even Steinbeck himself, when asked if he deserved the prize, said, "Frankly, no."

A Prize with Political Implications

It's important to note that the Nobel Prize is not, like the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award, granted for a single work. Rather, it's an award for an author's body of work. In the case of Steinbeck, most people felt that his body of work was not strong enough to merit such a prestigious award. While his works had literary merit, Grapes of Wrath seemed to stand alone as Steinbeck's enduring contribution to literature. Critics would (rightfully) argue that it's not enough to garner a Nobel Prize.

But the Nobel Prize in Literature also has a history of being intertwined with politics. When Boris Pasternak won the prize in 1958, his award was just as much about reviling Russian Communism as it was about honoring exceptional literature. (Alas, Pasternak was forced to decline the award.) And the 2013 winner, Mo Yan, has made waves with his commentary on China's politics. Grapes of Wrath undoubtedly had equal--if not greater--impact on American politics at the time of its publication.

So what do you think? Should the Nobel Committee acted differently in 1962? Should they have declined to name a winner that year, as they'd done in several previous instances?

Source: The Guardian