For the entire first half of the twentieth century, Edgar Rice Burroughs was the most widely read American author. As per a 1963 statistic of Life Magazine, Burroughs' paperback books were runaway best-sellers; over ten million copies sold within just one year of their release, accounting for a full thirtieth of US annual paperback sales. While Burroughs' beloved tales are certainly popular for their fantastic plots and classic characters, interest in the books has been spurred by controversy.

Racy Scenes and Racial Tension

Born in Chicago on September 1, 1875, Edgar Rice Burroughs failed at multiple careers--from railway policeman to gold miner--before turning to writing. In 1912, he published his second novel, Tarzan of the Apes, to All-Story  Magazine and received $700. The story struck a chord with contemporary audiences. Readers clamored for Burroughs' tales of adventure and science fiction. Though the author would never get rich, he did make quite enough to live comfortably and was among the first authors to "cash in" on his literary success with a series of film adaptations and related merchandise.

Magazine and received $700. The story struck a chord with contemporary audiences. Readers clamored for Burroughs' tales of adventure and science fiction. Though the author would never get rich, he did make quite enough to live comfortably and was among the first authors to "cash in" on his literary success with a series of film adaptations and related merchandise.

Burroughs' works also raised many an eyebrow at the time. Female characters wore little clothing, rape was frequently threatened, and characters turned to violence. The works were considered too lurid for genteel readers of the time. That alone probably spurred readers' insatiable desire for Burroughs' novels and short stories.

But by the time Burroughs passed away in 1950, his books had faded into relative obscurity, except for reprints published through Grosset & Dunlap. But in 1961, a California librarian decided to remove a Tarzan title from the shelves. She argued that Tarzan and Jane were "living in sin." This was not actually the case; Burroughs had gone to great pains to emphasize the couple's marriage, thereby making his tale more palatable to genteel readers. Nevertheless, the banning of Tarzan brought renewed interest to all of Burroughs' works.

On March 11, 1970, Tarzan would again spark controversy. On that day the editors of the Yale Record hosted a private screening of "Tarzan the Ape Man" starring Johnny Weissmuller. The 66-year-old Olympian was the guest of honor, and he was scheduled to give a talk after the movie. However, a group of about twenty students protested by stepping in front of the movie projector, literally blocking the picture from showing on the screen. The group protested Burroughs' "attitudes of white supremacy."

On March 11, 1970, Tarzan would again spark controversy. On that day the editors of the Yale Record hosted a private screening of "Tarzan the Ape Man" starring Johnny Weissmuller. The 66-year-old Olympian was the guest of honor, and he was scheduled to give a talk after the movie. However, a group of about twenty students protested by stepping in front of the movie projector, literally blocking the picture from showing on the screen. The group protested Burroughs' "attitudes of white supremacy."

An Antiquated Worldview

Burroughs was unfortunately obsessed with white supremacy. In "ape speak," he says, Tarzan means "white skin." Tarzan is also high born, the son of British nobility. Thus Burroughs pointedly created a white king of the African jungle. Proud of his own nearly pure Anglo-Saxon heritage, Burroughs was, unfortunately, hardly an anomaly of his time.

Tarzan represented the intersection of good breeding and the concept of survival of the fittest--and the viewpoint that the white upper class was meant to rule the world. In his Mars series, Burroughs creates an equally WASP-y hero in John Carter, the "gentleman from Virginia." And the Green Martians are considered morally inferior to the Red Martians, who have distant white ancestors.

Tarzan represented the intersection of good breeding and the concept of survival of the fittest--and the viewpoint that the white upper class was meant to rule the world. In his Mars series, Burroughs creates an equally WASP-y hero in John Carter, the "gentleman from Virginia." And the Green Martians are considered morally inferior to the Red Martians, who have distant white ancestors.

The white-man-as-natural-ruler trope played into fears of what historians sometimes call the "mongrelization of America," that is, the fear that Anglo-Saxon whites would lose their place of power in American society. By this time, immigration from Eastern Europe had reached an all-time high. Meanwhile, European colonial empires were rapidly eroding. Later, the Great Depression only exacerbated animosity toward immigrants and non-whites.

Meanwhile Burroughs also openly espoused the use of eugenics, which wasn't that far from the American mainstream mindset of the era. In 1927, Burroughs covered the kidnap-murder trial of William Edward Hickman for the Hearst newspapers. He argued that "moral imbeciles" and "instinctive criminals" should be exterminated--along with their relatives, who might pass along the same corrupt genes to future generations. It's a wonder that Burroughs didn't identify more strongly with the Nazis...which was only because of his deep dislike of the Germans.

Yet history has been kind to Burroughs, mostly forgiving the overt racism of his works as evidence of his zeitgeist. Modern reprints and adaptations of his books use softened language or remove offensive language and scenes entirely. For example, Burroughs' Tarzan enjoys "baiting blacks" as his "primary divertissement." In the animated adaptation, Disney presents an Africa with no citizens, eliminating the possibility of interaction between the protagonist and any African people. And that description of Tarzan hardly appears in today's reprints.

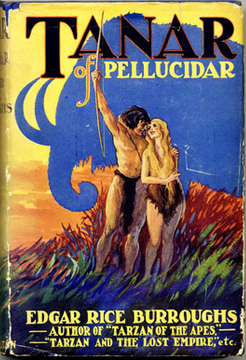

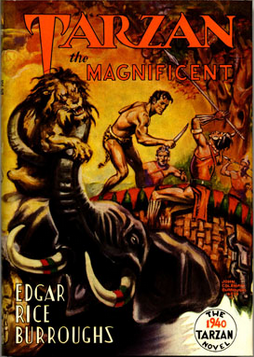

Collecting Edgar Rice Burroughs

Collectors of Burroughs often similarly forgive or overlook his offensive opinions, choosing instead to focus on nostalgia and escapism. Indeed, some even eschew John Taliaferro's biography of Burroughs, Tarzan Forever, because Taliaferro dares to delve into the unseemly aspects of Burroughs' worldview. Burroughs  remains an incredibly popular figure among collectors of modern first editions, so much so that an entire industry has developed around creating facsimile dust jackets for Burroughs books.

remains an incredibly popular figure among collectors of modern first editions, so much so that an entire industry has developed around creating facsimile dust jackets for Burroughs books.

Because Burroughs was such a prolific author, one cannot underestimate the importance of a Burroughs bibliography. Irwin Porges' profusely illustrated Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Man Who Created Tarzan offers an excellent foundation for new collectors, while Robert B Zeuschner's Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Exhaustive Collector's and Scholar's Descriptive Bibliography is the preferred reference for more advanced collectors.