Of the great writers of the 20th century there were a tremendous number battling serious mental illness. Virginia Woolf struggled with bipolarity throughout her life, eventually killing herself in 1941; Hemingway was beset by a crippling depression that led to alcoholism and eventually suicide; Robert Lowell spent time in a mental hospital, as did Sylvia Plath and David Foster Wallace, both of whom famously committed suicide after producing works of monumental importance dealing with, among other things, the horrors of depression. As we go back further, we encounter the likes of Leo Tolstoy and Thomas Hardy. Everyone on this list is rightly idolized by modern writers and readers, but do we risk simultaneously idolizing the diseases that ultimately killed many of them?

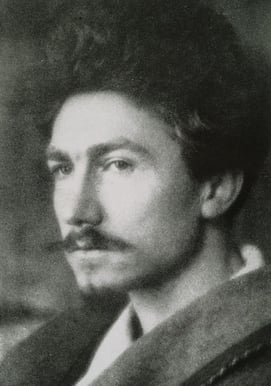

One of the thorniest cases of trying to disentangle a writer’s work from his or her mental afflictions comes with reading Ezra Pound. T.S. Eliot (not the happiest man on the planet himself) said of Pound that he "is more responsible for the twentieth-century revolution in poetry than is any other individual," a sentiment that many other writers have shared since his death.

One of the thorniest cases of trying to disentangle a writer’s work from his or her mental afflictions comes with reading Ezra Pound. T.S. Eliot (not the happiest man on the planet himself) said of Pound that he "is more responsible for the twentieth-century revolution in poetry than is any other individual," a sentiment that many other writers have shared since his death.

His verse was formally innovative, drawing influences from Chinese and Japanese poetry, and notoriously difficult. The modernist rallying cry, “Make it new,” originated with Pound, who saw himself more as an advocate for great poetry than a great poet himself—helping writers like Eliot and James Joyce publish some of their early works and generally championing their artistic abilities. In July 1908, he self-published his first book of poems in Paris. By 1945 he would be residing in the windowless prison wing of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital.

Of course, Pound’s road to the mental hospital took more intricate turns than those of many of his contemporaries. In particular, his journey included a long love affair with Fascism. Following the carnage of the First World War, Pound became disillusioned with finance and capitalism. This may not have been an unreasonable reaction in and of itself, save for the fact that in Pound’s mind, capitalism was synonymous with Judaism. After a time spent advocating for fascistic policies in the United State, Pound ultimately moved to Italy, where he met with Benito Mussolini. The fact that Mussolini had apparently read some of Pound's Cantos (1915-1962) and found them diverting seemed to really set the poet over the edge. He opted to stay in Italy, where he helped the Fascist war effort by writing anti-Semitic propaganda for Italian newspapers and giving a series of radio broadcasts railing against FDR, decrying the influence of the Jews, and supporting the cause of Hitler’s Third Reich.

When the war in Europe was drawing to a close and the Allies had captured Italy, Pound fled from Rome on foot, walking more than 450 miles to Bologna before taking a train to meet his family. Shortly thereafter, Mussolini was killed and Pound was arrested and handed over to the Americans. He was imprisoned for treason.

Pound, not entirely getting the message, spent some time offering to help the United States broker peace with Japan and scripting out more radio addresses before it became clear that he was not going to be allowed to return to a normal life (no doubt the chances of such were even further diminished when, following Germany’s surrender, he compared Hitler favorably to Joan of Arc). Eventually, he was transferred to a disciplinary facility in Pisa, where for several weeks he was held outdoors in a six foot by six foot steel cage. There, under those conditions, he began work on what would come to be known as the Pisan Cantos, some of his most memorable and perplexing verse. There, also, he finally suffered a complete mental breakdown.

Once Pound was transferred to America (where he would eventually leave St. Elizabeth’s for slightly less draconian accommodations), he was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder and never had to stand trial for treason. His friends, Eliot and Hemingway among them, spent many years attempting to have him freed—leveraging financial support and literary accolades to clear his reputation. Though they would eventually succeed, it’s not clear that Pound deserved their efforts. He had become embittered in his relative old age, and his anti-Semitic attitudes had persisted along with his tendency toward fascism. Still, Pound was able to move back to Italy, about which occasion he remarked, “When I left the hospital I was still in America, and all America is an insane asylum.”

Once Pound was transferred to America (where he would eventually leave St. Elizabeth’s for slightly less draconian accommodations), he was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder and never had to stand trial for treason. His friends, Eliot and Hemingway among them, spent many years attempting to have him freed—leveraging financial support and literary accolades to clear his reputation. Though they would eventually succeed, it’s not clear that Pound deserved their efforts. He had become embittered in his relative old age, and his anti-Semitic attitudes had persisted along with his tendency toward fascism. Still, Pound was able to move back to Italy, about which occasion he remarked, “When I left the hospital I was still in America, and all America is an insane asylum.”

If America can be said to be an insane asylum, the same can probably be said of the world of letters. But again, Pound's case is a slightly thorny one. How can we enjoy his poetry when it is so tangled up with his abhorrent political views? Though the answer is hard to articulate, for many it is eminently doable—Donald Hall, for instance, has been singing Pound’s praises for years. This all raises the question: if we can, for Pound, so effectively separate the writer from his work, can we, in the cases of Woolf and Hemingway and the others, separate the writers from their illnesses?